SASKATOON — Beetles can be pests, especially flea beetles, which can wipe out a field of canola seedlings in a matter of days.

But not many species of beetles, out of about 360,000 species that exist, are actually helpful.

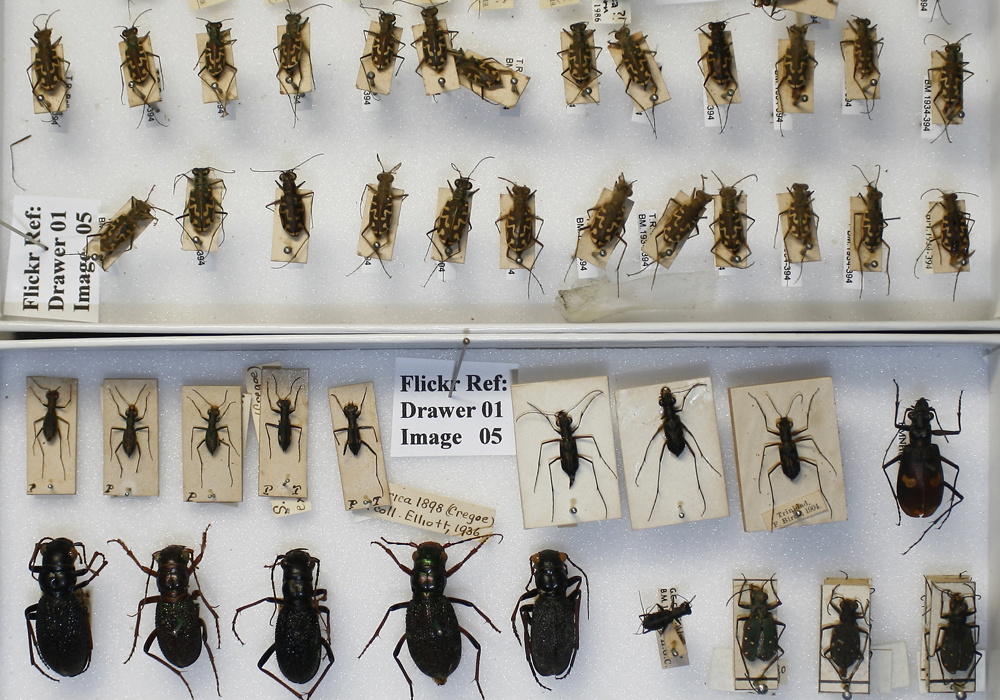

That includes the carabid family of beetles, which like to feast on weed seeds.

Studies suggest these beetles can consume a large percentage of weed seeds, as high as 70 percent of seeds that fall onto the soil.

Those studies are from Europe, where the climate is much different than Western Canada, said Christian Willenborg, a University of Saskatchewan weed scientist. However, beetles, crickets, mice, birds and earthworms could be eating a massive number of weed seeds on Canadian farm fields as well.

Read Also

Farming Smarter receives financial boost from Alberta government for potato research

Farming Smarter near Lethbridge got a boost to its research equipment, thanks to the Alberta government’s increase in funding for research associations.

“Growers aren’t thinking about it because they don’t see it,” said Willenborg, who spoke Dec. 3 at the Farm Forum Event, held in Saskatoon.

“These seed predators are there and if we encourage them, they can make a big dent.”

During his talk to an audience of about 60, Willenborg said four primary sources contribute to the seed bank — the combine, weed seeds in the soil, seeds on the soil surface and standing weeds.

Most of the emphasis is on killing standing weeds before they shed seeds that return to the soil.

But dozens of weeds have developed resistance to herbicides, so spraying weeds is becoming less effective.

It might make more sense to stop the life cycle of weeds at an earlier stage — before the seeds get into the soil and germinate.

“Once your weeds have emerged it’s almost a back-end strategy (to spray),” Willenborg said.

Other weed scientists have a similar viewpoint — killing weeds on the surface is not sufficient.

“Despite efforts to eliminate weeds, they continue to thrive. Weed persistence is reliant upon the soil seed bank,” said Lauren Schwartz-Lazaro, a Louisiana State University weed scientist, in a 2019 paper published in Agronomy.

“The natural longevity of the (weed) seed bank suggests that alternative or additional weed management tactics are required to reduce the store of weed seeds.”

If producers can help predators, like beetles, eat more seeds, it could reduce the amount of weed seeds that return to the seed bank, and limit the amount of weeds that emerge.

“They (predators) can make a big difference but they’ll never be the ultimate solution,” Willenborg said.

“You have to have something above ground that’s going to reduce the density of those seeds (falling to the ground).”

That’s because certain weeds, like redroot pigweed, can produce 100,000 seeds per plant. There could be millions of weed seeds on the soil and the beetles cannot keep up.

Nonetheless, European farmers are already using beetles and other predators to eat weed seeds that fall on the soil.

Producers in Europe use something called a beetle bank, a narrow strip of grass and natural vegetation.

“There is big uptake in Europe,” Willenborg said. “(They) are kind of like pollinator strips … in the middle of your crops.

“These provide an overwintering habitat for those beetles.”

European farms are small and nothing like Western Canada, but a few producers are doing something similar in Saskatchewan.

Willenborg knows of one farmer who places bales next to his cropland. The bales are a source of shelter for beetles and mice, which feed on weed seeds in the warmer months.

If a producer doesn’t want to have a natural area, or beetle bank, there are other options to assist weed seed predators:

- Growing cover crops can help, perhaps between the rows, because the vegetation provides a protective habitat for beetles.

- Reducing tillage. Beetles can survive in crop stubble, but will perish in bare soil.

- A diverse crop rotation.

In the last few years, another non-chemical means of managing weeds has generated a lot of press — the Harrington Seed Destructor.

Invented in Australia, the machine is towed behind or built into the back of a combine. It collects the chaff and uses a cage mill to pulverize weed seeds.

Research shows the technology is highly effective, destroying about 95 percent of weed seeds.

It works, but it’s not a magical weapon, Willenborg said.

“If there’s something in the weed science world that’s (presented) as a silver bullet, (it) never lasts,” he said.

Part of the problem is that a weed may shed its seeds before the combine arrives on a field, especially in a year like 2019 when combining was weeks later than normal.

Or, weeds could evolve harder seeds that survive the Harrington Destructor.

“No matter what we do, there’s still going to be weed seeds that fall to the ground,” Willenborg said.

“(So) seeds will fall to the ground and my question is, what are we doing about it? More often than not, it’s nothing.”