A group of durum growers from Saskatchewan, North Dakota and Montana want to get into the pasta business.

Prairie Pasta Producers is awaiting results of a feasibility study for a pasta plant that would process between three and four million bushels a year. That report is expected July 14.

Prairie Pasta Producers was formed last fall when an American group, Mon-Dak Durum Producers, asked Saskatchewan farmers to join them.

At least one observer is waiting to see where the study suggests the plant be built.

Read Also

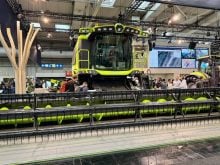

Agritechnica Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year

Agritechnica 2025 Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year.

Dion McGrath, co-operative development specialist for the Saskatchewan government, is concerned there might be confusion about the government’s attitude toward new-generation co-ops that will put a Saskatchewan location at a disadvantage.

A brochure published by the group says the plant will likely be built in North Dakota.

“Why? 1. This project was their initiative,” the brochure said. “2. North Dakota allows closed co-operatives. In other words, the durum producers can totally own the durum mill and pasta plant.”

Harlan Johnson, a steering committee member from Crosby, N.D., said producers want to use a new generation closed co-operative model to capture more of the consumer dollar.

Len Rutledge of Carievale, Sask., another committee member said: “We can’t build it here (Canada) because there are no rules to allow a closed co-op.”

But McGrath said that is not true. Saskatchewan already has closed co-ops in other sectors, for example housing and daycare co-ops.

“This type of co-op connects the producer’s raw product into a finished marketable product,” McGrath said. “Once you’ve defined the market, once you know your capacity … then in effect your membership closes.”

In closed co-ops, an investment in the co-op gives the farm the right to deliver grain to the plant.

One difference between Saskatchewan and North Dakota co-ops is voting privileges, he said. North Dakota allows for non-producer equity investment with no vote.

In Saskatchewan, “a member is a member,” he said, which should encourage total ownership by farmers.

McGrath is working with two other agricultural groups in the province – chicken and Boer goat producers – who are forming new generation co-ops.

He said the Prairie Pasta Producer’s apparent favoritism for North Dakota probably is linked to misinformation among the producers.

“(American producers) would like to see it built on their side and right now the majority of support is coming from Saskatchewan,” he said.

Johnson said between 500 and 600 producers had contributed $250, or $200 U.S., to a seed money fund by mid-June. At least half are Canadian.

“I think our American counterparts were quite taken aback” by the response, said the committee’s international secretary Judy Riddell in Carlyle, Sask.

Riddell said preliminary reports from the feasibility study are positive. She expects the group will proceed with a business plan immediately.

“We’ll have to run some numbers and see what size looks best,” Johnson said.

A prospectus giving details of the investment plan will follow and an equity drive is expected in early 1999, before farmers start seeding. The committee said the plant will cost at least $60 million, and durum producers would have to raise at least $20 million in equity.

Johnson said the new generation co-op model will help keep the price of durum fairly constant. Producers will benefit from dividends from the value-added processing in times of low durum prices.

“We are proving that Canadian and American farmers can work together,” Johnson said. “We all face the same problems.”

Riddell said there is a perception the Saskatchewan government hasn’t been “quite as receptive” to the new generation co-op model.

“But the bigger problem (producers) have, of course, is dealing with the wheat board.”

She said after the feasibility study is received Prairie Pasta will put an “irresistible” package together and present it to the board.

Rhea Yates, Canadian Wheat Board information officer, said the organization is awaiting the package.

“When we get that detailed proposal we will seriously consider it. It is not our objective to stop proposals like this from going through,” Yates said.

The board treats all domestic processors the same, selling grain at prices determined by North American futures markets.

“If there are special arrangements that won’t be at the expense of other farmers participating in the pool accounts, then we will do what we can,” said Yates.