Canadian farmers are known for their ability to adapt but they will need continued investments to help them find climate change solutions, organizations told the House of Commons agriculture committee recently.

Producers are feeling the effects of climate change in different ways, said Andrea Brocklebank, executive director of the Beef Cattle Research Council at the Canadian Cattlemen’s Association. For example, she said cold winters traditionally prevented parasites and diseases from surviving but producers can no longer count on that.

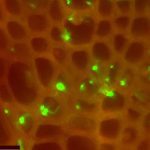

She told the committee that dog ticks that can carry anaplasmosis, which causes abortion, anemia and productivity losses, used to be found only in southern Manitoba and eastern Saskatchewan.

Read Also

VIDEO: Potato video highlights importance of water conservation

Potato Growers of Alberta release the third of a five-part video series, highlighting the potato industry’s efficient use of water to tend to their acres producing the high-value crop during drought conditions.

“Recent research has found this tick farther north in Manitoba and as far west as Alberta,” she said. “Widespread ticks will make it much easier for anaplasmosis to spread.”

That is just one example of the animal health and welfare implications of climate change.

More extreme weather events increase the risk of crop failure at a time when increased productivity is required. More land might be converted to pastures as a result, Brocklebank said. This points to the need for investment in forage and grassland research.

“Government can play an important role in building resiliency to climate change through research by fully funding the proposed third beef science cluster, and furthermore, we recommend the funding of the smart agri-food supercluster, investing in long-term higher risk discovery research and investing in critical research infrastructure and capacity,” she told the committee.

CCA also advocates improved hay and forage insurance that could replace calls for AgriRecovery after a weather-related disaster.

Canadian Federation of Agriculture president Ron Bonnett agreed investing in research is critical. He said everyone needs a better idea of how to adapt to the changing climate, not just mitigate.

He pointed to British Columbia’s climate action initiative as an example of how regional workshops help producers develop their own adaptation strategies that fit their operations and their locales.

Manitoba plans to soon release a report on adaptation initiatives in that province.

CCA and CFA both spoke to the need for improved disaster response programs.

Brocklebank said the program has to be sufficiently funded and consistently delivered. AgriRecovery has been used in several cases of weather-related disasters but not all of them. She said it must contain clear triggers.

“Historically, AgriRecovery’s dependence on political decision-making during a disaster has compounded confusion in challenging times and made planning for disasters enigmatic for producers,” she said.

She said producers have to make decisions quickly during a disaster and don’t often know if funding is available at all and what is eligible.

Bonnett said program designers also should consider that disasters aren’t necessarily one-time events.

“Sometimes a disaster is something that goes on gradually and you wouldn’t have a disaster declaration,” he said. “It can be a progression of events.”

The agriculture committee is studying climate change and water and soil conservation and is likely to commit this week to studying rural mental health.