How do you get rid of a prion? Will meatless Mondays have an effect on global warming? What’s the real story behind antibiotic resistance? And can you ride a mountain bike across a busy Alberta city in a snowstorm?

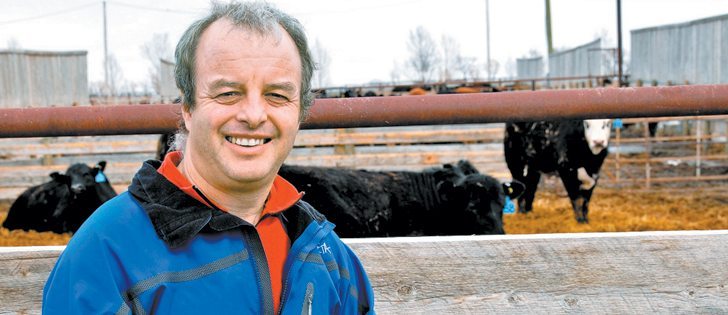

Tim McAllister, principal research scientist at Agriculture Canada’s research centre in Lethbridge, is trying to find answers to all these questions with considerable success, though the last question on the list requires the least amount of research.

The internationally known ruminant microbiologist is an avid cyclist, but work is his major passion.

Read Also

Organic farmers urged to make better use of trade deals

Organic growers should be singing CUSMA’s praises, according to the Canadian Chamber of Commerce.

“I like being busy. I never have to think about what I’m going do for a minute when I’m at this office. I could work 24 hours a day if I wanted.”

Sometimes he does, by all accounts. Years ago, his habit of sleeping in the lab while doing research for his master’s degree convinced renowned ruminant microbiologist K.J. Cheng to accept him as a doctoral student.

Even now, McAllister exults in international research collaborations that allow him to work longer because of different time zones. At the Lethbridge Research Centre, he manages about 50 people working on various research projects.

McAllister chooses to lead his team by example, spending hours in his office reviewing data and planning future research directions.

“A big part of science is being able to see into the future and seeing what issues are going to arise,” he said.

“All of my program is based on a huge team of people, and each of us bring different skill sets to the table. Seeing the future and where things are going is what I bring, that’s my skill set. But without everybody’s skill set, we don’t deliver on the final product. I’d be pretty useless without everybody else.”

Evidence of his success is plentiful, but pride of place in his office is reserved for a 2007 Nobel Peace Prize, awarded to him as a member of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The panel shared the award with former U.S. vice-president Al Gore in recognition of raising international awareness of global warming.

McAllister grew up on a farm near Innisfail, Alta. He switched to agriculture during his second year of university zoology studies because he figured he could always use it back on the farm.

He met his wife, Kim Stanford, while both were studying at the University of Alberta. When Stanford got a job in Lethbridge after they both earned their degrees, McAllister followed.

After a few different jobs and a PhD from the University of Guelph for McAllister, they both ended up in research, he with Agriculture Canada and she with Alberta Agriculture.

“We work really well together. She’s got skills that I don’t have. She’s great at statistics and I’m not as good at statistics as I should be,” McAllister said.

“We collaborate together a lot. A lot of work on E. coli O157 we do jointly.”

McAllister has travelled to every continent except Antarctica in pursuit of his research and at the invitation of various organizations and academic institutions. He’s an adjunct professor at five Canadian universities, another in Australia and another in China.

His reputation also attracts numerous post-doctoral students and researchers who want to work with him.

That’s in no small part due to the fact that McAllister’s team gets results. Agriculture Canada scientists in Lethbridge are expected to publish at least two papers per year. This year McAllister and his team will publish 52.

“We’re doing some really neat stuff. And the thrill of discovering things that nobody else in the world knows and the thrill that they have of being the first ones to do that (keep his team members motivated),” he said.

“I’m here to help them, but I also emphasize a lot of independence. You sort of determine your own success or failure. You really need to have passion for science because it’s incredibly competitive and you’re kicked around continuously.”

McAllister admits it’s been awhile since he’s slept in the lab or juggled test tubes. His time is now better spent guiding research, polishing content in papers and collating all that he reads into a sense of where research should go next.

Right now, some of his attention is focused on food safety and misinformation about livestock production.

“A lot of our program now is putting some science around those issues.”

McAllister is sought as a speaker on the numerous topics within his area of expertise. The best part of that is when he sees the “a ha” moment dawning on faces in his audience.

But he also knows he’s only as good as his last success.

“If you achieve an international reputation, it’s kind of like being a hockey player. As long as you’re scoring goals and assists, you’re seen as being in the top, but as soon as you stop scoring they want to send you to retirement.”

McAllister said reduced government funding for agricultural research is a concern, and the quest for project funding is never-ending. Companies and corporations support some of his team’s projects.

“One thing I make perfectly clear to those companies when they come here is that I’m going to publish the information whether it’s positive or negative, and I never accept a contract with a company that won’t allow me to publish information.”