A continuing dispute over exports of canola meal to the United States is having an impact on the canola crushing business, say industry officials.

Four or five of Canada’s 10 canola crushing plants are on an “import alert” list maintained by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration due to salmonella contamination.

The issue first arose in the fall of 2008, when a shipment from Cargill’s plant near Saskatoon was identified by the FDA as contaminated.

In the following months, plants operated by Bunge Canada in Ontario and Saskatchewan, Associated Proteins (since bought by Viterra) in Manitoba and Leblanc and Lafrance in Quebec have been subject to an import alert.

Read Also

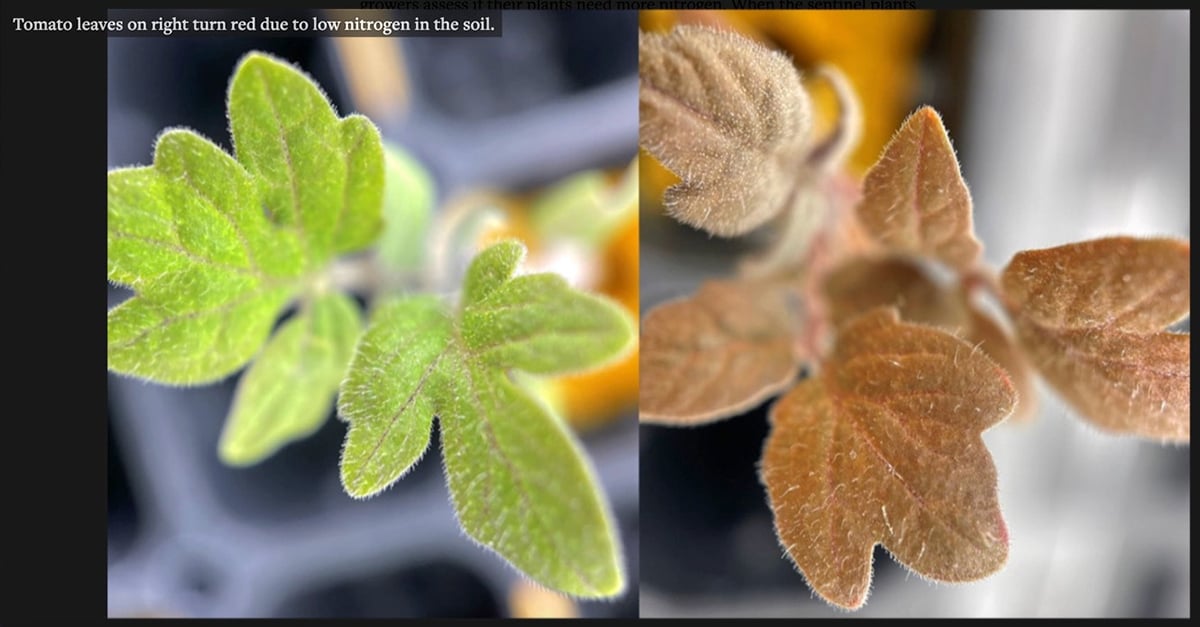

American researchers design a tomato plant that talks

Two students at Cornell University have devised a faster way to detect if garden plants and agricultural crops have a sufficient supply of nitrogen.

An import alert signals FDA inspectors that there is enough evidence to refuse admission of a product into the U.S. without physical inspection.

The FDA could not be reached to confirm which plants are on the list.

Company and industry officials referred questions to the Canadian Oilseed Processors Association, which represents the crushers.

COPA president Bob Broeska could not be reached for comment.

Market watchers say the border problem is affecting canola prices.

A report from Resource News International last week quoted brokers as saying sluggish demand from domestic crushers was undermining prices.

It said crushers are pulling back from the market due to eroding margins and the inability to move canola meal into the U.S. because of the salmonella issue.

The domestic disappearance of canola, which reflects crushing volumes, is down by five percent so far this crop year to 550,000 tonnes.

Since the beginning of August, crushing plants have been operating at around 70 percent of capacity, crushing about 69,000 tonnes a week.

Dave Hickling, vice-president for canola utilization with the Canola Council of Canada, said while canola meal continues to move into the U.S. from unaffected plants, the closure is beginning to have a significant impact.

“Canola crush numbers are still fairly strong so it’s not a total collapse by any means,” he said. “But certainly it’s being impacted, no question.”

More than 95 percent of Canada’s exports of canola meal go to the U.S.

Export statistics show a big drop in shipments to the U.S. in May 2009, around the time the FDA began putting plants on the import alert list.

Companies affected by the issue have been in direct contact with the FDA and are carrying out tests on their plants in an effort to get off the agency’s import alert list.

In addition, COPA has been involved in informal discussions with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency aimed at devising a long-term solution.

Broeska was recently quoted by a Manitoba radio station saying the problem isn’t an increase in the amount of pathogens in canola meal, but a change in FDA policy to zero tolerance for salmonella.

“We think that’s more a kind of policy decision that would be made on a food ingredient rather than a feed ingredient, which is far from the beginning of the human food chain,” he said.

To get off the import alert list, importers must provide results of third-party laboratory analysis proving the products are free of contaminants.

No information has been provided by government or industry groups on key questions such as how canola meal was stopped at the border, what happened to the shipments, how the contamination occurred, the level of contamination or what is being done to remedy the situation.