SASKATOON — India has temporarily dropped all pea import restrictions and that is breathing life into yellow pea prices.

The restrictions have been lifted from Dec. 8, 2023, through March 31, 2024.

“This is the first time in roughly six years that India has truly opened up to pea imports,” Greg Cherewyk, president of Pulse Canada, said in an email.

Read Also

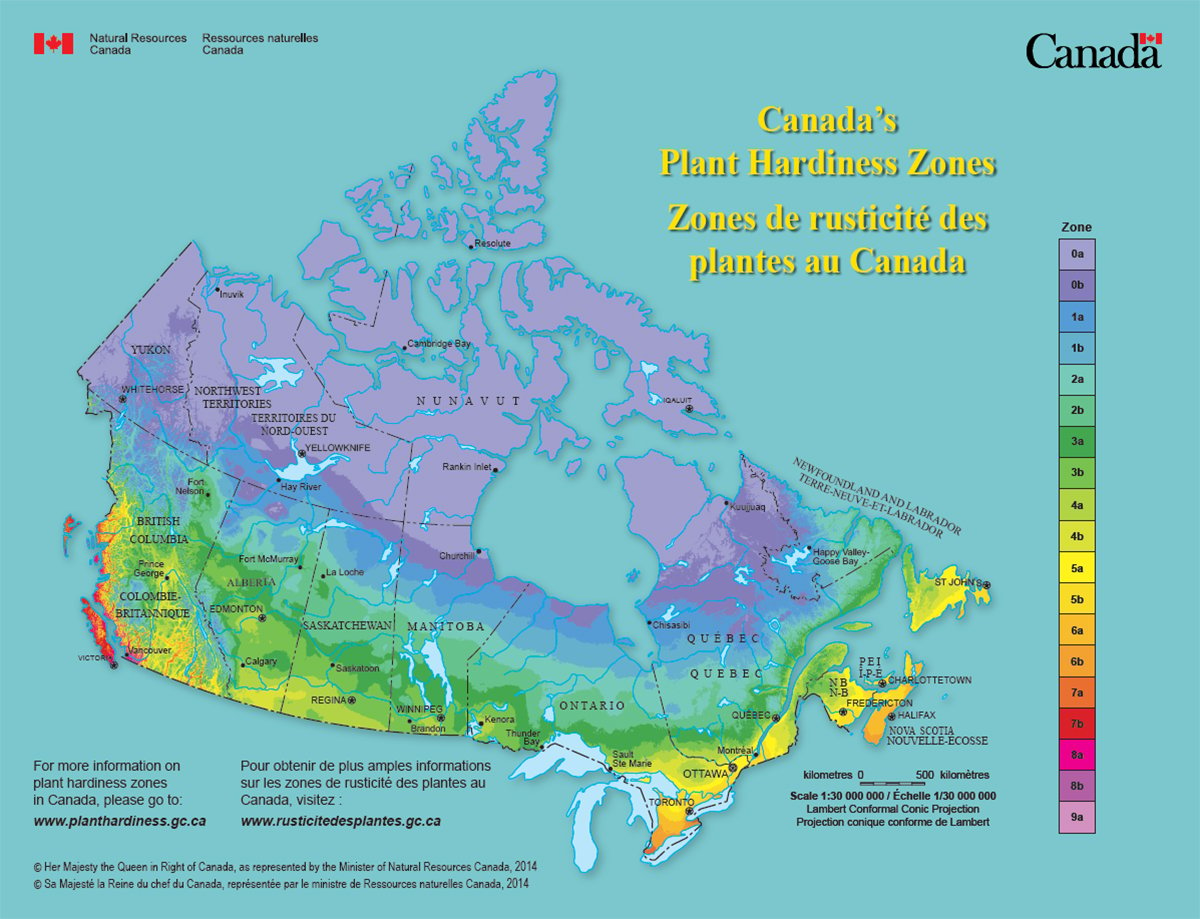

Canada’s plant hardiness zones receive update

The latest update to Canada’s plant hardiness zones and plant hardiness maps was released this summer.

“As a longtime supplier to the market, it’s great to see India open for business again.”

Yellow pea bids were in the $11 to $12 per bushel range the day following the Dec. 7 announcement, with one bid as high as $12.80.

That is up from $10.75 to $11 a week ago.

“They are coming up pretty quickly here,” said Marlene Boersch, managing partner with Mercantile Consulting Venture.

“That’s a significant increase.”

India first imposed a 50 percent duty on peas in November 2017. That was followed in early 2018 by a series of other restrictions.

Import volumes were limited to 150,000 tonnes annually. The minimum price on imports was set at 200 rupees per kilogram, or approximately US$2,400 per tonne. And imports were restricted to the Port of Kolkata.

All those constraints have been lifted.

The hope is that will lead to a resumption of trade with what used to be Canada’s top pea market.

Sales peaked at 1.59 million tonnes in 2011. They began to freefall in 2018 and have been essentially non-existent the last few years.

Pulse Canada said trade contacts indicate it will take between 60 and 65 days to get product from Canada to India.

“So, while the window is narrow, Canadian farmers and exporters can deliver prior to March 31, 2024,” said Cherewyk.

Shippers will need to get product to India by mid-March because it has to clear customs, which can take seven to 10 days.

He said it is difficult to estimate how much volume will move because of the short time period and competition from other origins.

Boersch said it would be “silly” to throw out a number because there are too many variables.

“It could be quite a lot,” she said.

“It depends a little bit on people’s logistics.”

There is interest from exporters who until recently were reluctant to take a position in the yellow pea market.

“That has changed profoundly, indicating to me there’s a lot of interest to get it in there,” said Boersch.

“The hunger for doing some more aggressive bulk exports of peas is going to be there.”

But there are plenty of Russian peas for sale and they are cheaper than Canadian product.

“I would be surprised if they aren’t looking that way as well,” she said.

Cherewyk doesn’t know if this will be the start of a permanent resumption of trade with the world’s pulse-consuming behemoth. But for now, all the import restraints are scheduled to be reinstated on April 1, 2024.

“We, along with our partners in the global pulse community, continue to advocate for consistent and predictable trade policies that ultimately provide greater certainty for everyone in the pulse value chain, including consumers.”

Cherewyk can only guess why India suddenly suspended the import restrictions.

“It’s probably safe to say that governments around the world are taking action to reduce the cost of living and food is a major contributor to that cost,” he said.

Others have speculated that India’s rabi or winter chickpea crop is off to a bad start because of El Nino-related dryness. Yellow peas are used as a substitute to desi chickpeas in India.

The Indian government said farmers harvested 12.27 million tonnes of chickpeas in 2022-23, but G. Chandrashekhar, senior editor with the Hindu Business Line, believes the crop was no bigger than 11 million tonnes.

The government has set an ambitious target of 13.65 million tonnes for 2023-24, but some analysts think production will be below last year’s level because of poor monsoon and early rabi season rainfall.

Desi chickpea and yellow pea prices have been rising in India since mid-summer, reflecting tight supplies of the crops.

Boersch doesn’t know where the shortage is, but it is obvious that India needs more pulses at cheaper prices.

She said it is nice to have a commodity showing some signs of life in what has been an otherwise moribund market for the major crops.

“Even opening the valve a little bit is a very positive thing,” she said.

Contact sean.pratt@producer.om