After staring at supply-demand ratios and historical futures price graphs, I’ve concluded that crop markets are in a similar state to what they were in the early spring of two years ago.

And I wonder if analysis of supply and demand will return as the key factor dominating crop price movement after a year when other issues such as anxieties about war and rampant inflation dominated the headlines

I’ll stick my neck out and suggest that anxieties will have a smaller role this year.

The terrible war in Ukraine continues and uncertainty about inflation, interest rates and potential recession persists, but it is human nature to adapt and I think we’ll see less anxiety in markets. There could be a sense of operating in the new normal.

That assumes, fingers crossed, we don’t get other shocks.

That was not the case last year when the shock of the war in Ukraine created a host of worries that caused traders to price in a risk premium to many commodities. Then worries rose that the fight against inflation, and more recently troubles in the banking sector, would push economies into recessions.

To counter that risk, traders wiped out the earlier risk price premiums.

In this see-saw of emotions and worries about trade and financial disruptions, the fundamentals of global crop supply and demand in markets sometimes appeared to take a back seat, overwhelmed by panic trading.

I will argue now that the current range of crop prices is more reflective of supply-demand fundamentals.

Furthermore, I’ll suggest that the current situation is similar to late March in 2021. And in both years, the supply-demand ratio forecast was fairly tight, justifying strong grain prices but not rallies to all-time highs.

I’ve set aside 2022 because it was topsy-turvy as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine caused prices to soar.

In March 2021, the COVID vaccines were starting to roll out. There was hope that things would get back closer to normal as the year progressed. There was no knowledge that drought would devastate Canada’s crop or that South America would also be dry.

In both 2021 and this year, global stocks of soybeans, corn and wheat were substantially tighter than they were on average in the 2014-19 period.

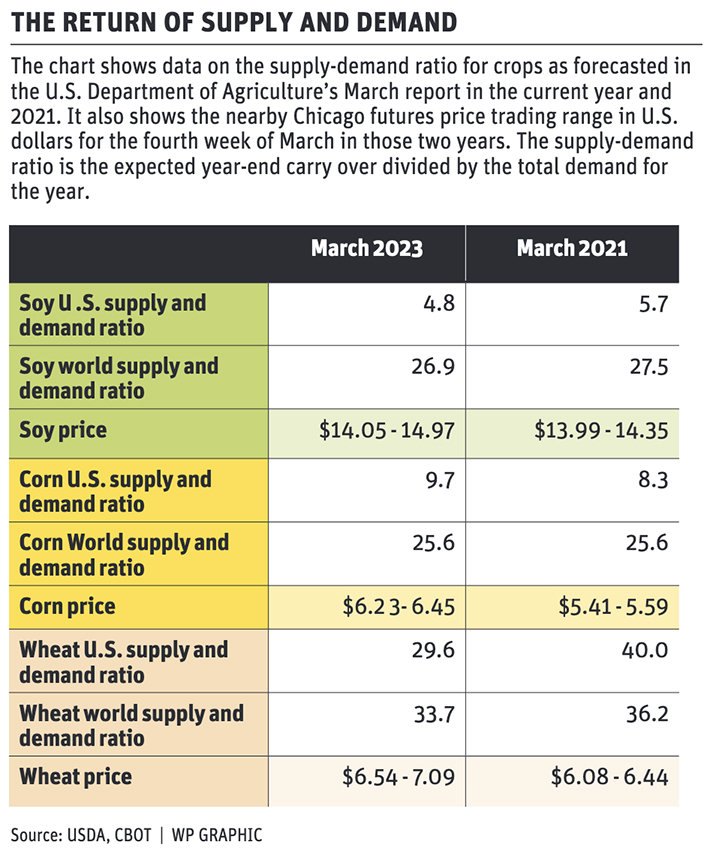

In the accompanying chart, you can see that the supply-demand ratio forecast for soybeans, both the United States and the world, is a little tighter this year than it was in March 2021.

The supply-demand ratio is the forecasted year-end stocks divided by total demand. A smaller number means that the stocks are tighter.

So we have a little tighter supply situation in soybeans this year and the Chicago futures price is a little stronger than it was at the same time in 2021.

That makes sense.

Looking at wheat, the supply-demand ratio for U.S. domestic supply this year is a lot tighter than in 2021 and the world ratio is a little tighter.

The Chicago futures price is roughly nine percent higher than it was in 2021.

So again, a tighter grain supply situation is generating a higher price.

However, in corn my argument breaks down a little.

Currently, the stocks-to-use ratio this year is a little higher in the U.S. domestic market than in 2021 and in the global situation the ratio is the same in both years.

You would think that would generate a futures price the same at 2021 or a little lower.

However, the price is 15.3 percent higher this year.

But I should note that in this exercise, using narrow snapshots in time, we don’t see the longer-term market trend.

In the 2020-21 crop year, corn prices were on a huge sustained rally. The U.S. had a disappointing harvest and China’s production was hurt by a late season string of typhoons.

In the late winter and early spring, China came in with big buys of U.S. corn and in April the price really soared, peaking in May above $7.50 per bushel.

This March, China is also making big purchases from the U.S. but I doubt that will fuel a similar rally above $7.50.

I hope we don’t encounter new crises that elevate anxieties and cloud supply and demand basics. We want the market to send signals that farmers can use to make long-term plans.

Artificially high prices associated with crises could spark overproduction that could weigh down prices for years.