The Bronfmans, who built a liquor empire and brought ‘Canadian whisky’ to the United States, started their journey in Western Canada

This is part of an ongoing series of stories exploring rye, the crop, as it becomes Rye, the whisky.

BIENFAIT, Sask. — The trains still rumble and sound their mournful horns through the middle of Bienfait in southeastern Saskatchewan, but the train station where Paul Matoff was blown away with a shotgun blast in 1922 is long gone.

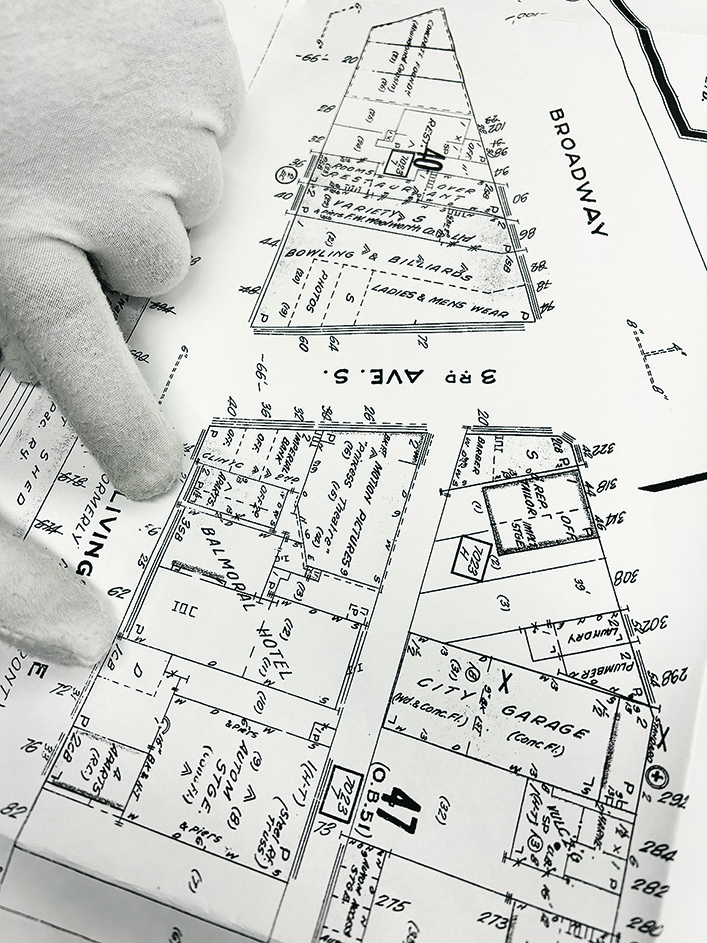

Further north in Yorkton, Sask., there are just parking lots where the Balmoral Hotel and City Garage used to stand across from that small city’s train station, which is now just a greasy bit of railside dirt. At one time the Balmoral hosted the longest bar in the West, and the garage was the recovery home for shot-up “whisky six” automobiles that had run-ins with U.S. authorities.

Other stories in this series:

- More producers start growing rye as crop prepares for a recovery

- Farmer finds new uses for old crop of rye

- Growing rye for seed is quirky but fun

- Rye’s agricultural journey set over thousands of years

- Hybrid varieties a game changer for rye sector

- Agriculture Canada plant breeder committed to rye

- Rye bread continues to nurture loyal following

Far to the east, on Main Street in Winnipeg, there is little to mark the history of the Bell Hotel. The building now serves mostly as a backdrop to the homeless people, those needing to get back on their meds, people dealing other kinds of drugs and a place too frightening for most city residents to visit. It isn’t the fancy joint it was a century ago.

All these locations are central to the Bronfman family saga, which began in early prairie communities such as Wapella, Sask., Emerson, Man., and Brandon and then migrated to Winnipeg and Yorkton. From here the world’s biggest liquor empire was born, matured and, like so many young products of the Prairies, headed east to seek fame and fortune. By the mid-20th century, anybody in the western world who drank whisky probably knew the name Seagrams, and that of its owner, the Bronfmans.

This is also part of the prohibition era milieu in which the terms “rye whisky” and “Canadian whisky” became stamped into American people’s minds — and confused forever. For tens of millions of people since the 1920s, “Canadian” and “rye” whisky have become synonymous, as well as “rye” coming to simply mean “whisky” for the average Canadian.

The important Bronfman brothers, Harry and Sam, built their liquor empire in bits and pieces, with no big plan, as these products of a Jewish family fleeing Russian persecution looked for ways on the western Canadian plains to eke out a living and advance their family from typical pioneer poverty.

Yechiel and Mindel Bronfman — a surname derived from “brewer” — homesteaded outside Wapella in 1889, relocating to Brandon in 1892. After years of helping their father with various small time ventures, such as hauling frozen fish and firewood and breaking wild horses brought in by American traders, eldest Abe and second-born Harry bought hotels in Emerson on the U.S. border and Yorkton with the Balmoral.

They soon discovered that the real money in the hotel business was from operating the bars rather than renting rooms. That began their journey into the complex, confusing and dangerous world of alcohol, both in serving and wholesaling.

The biggest hotel venture the Bronfmans took on was purchasing the Balmoral, an impressive three-storey brick structure, in 1905, with Harry becoming sole and proprietor in 1907. His name was painted atop the structure, facing all those arriving by train in Yorkton. Those were the days when a travelling salesman might need a room and place to relax, when tired working men might appreciate a few shots to take the edge off a day of labour and when bored townsfolk might look for a place to get out and about and hear the recent news and gossip. Harry was pleased to provide such a venue in what was considered by some to be the finest hotel west of Winnipeg.

The imposition of prohibition in Canada during the First World War threw a wrench into their plans — and presented them with the opportunities that made them rich and the southern Prairies infamous.

After initially watching their bar business die and the family finances torpedoed, Harry and his younger brother, Sam, began figuring out ways to remain in the liquor serving and wholesaling businesses that were, most of the time, just slightly on the right side of the law. The situation became much more complex, and lucrative, once prohibition was also imposed in the United States, just a tantalizingly few miles to the south of the Bronfman operations.

Harry and Sam found ways to obtain and wholesale liquor across provincial lines and into the U.S. They became adept at serving the all-of-a-sudden booming demand for alcohol from doctors and pharmacists besieged by patients needing prescriptions for the whisky cure. Colds, coughs, flus, rheumatism and other ailments became widespread in the prohibition era.

The Bronfmans entered the world of distilling alcohol, making blends, bottling and selling these industrial and medicinal products, few of which would please the palate of today’s uisgephiles. As prohibition south of the border created a booming demand for Canadian-sourced alcohol, the Bronfmans set up a network of liquor-dealing warehouses, known as “boozariums,” all along the border-hugging dirt road that is now paved and known as Highway 18 in Saskatchewan.

It was near one of these in 1922 where Matoff, Harry’s brother-in-law, met his untimely end. He had received $6,000 in cash for a load of Bronfman liquor sold to a North Dakota dealer earlier that day and was at the train station turning the cash over for safe delivery to Regina, when a shotgun barrel was stuck through a window and Matoff took delivery of a full load of lead shot. The gangsters held the station staff at gunpoint, stripped Matoff’s body of the cash and a $2,000 diamond stickpin and then took off at high speed, flying past Mounties in the next town who had no idea what had happened because the gunmen had cut the telephone wires on each end of Bienfait.

The murder caused outrage in Saskatchewan, as well as sending Harry into a lengthy depression. Younger brother, Sam, who had learned much about the business from working at the Balmoral, took control of the Bronfman family’s affairs in the next few years. He relocated the centre of the family’s operations to Montreal, which was much closer to the booming U.S. market for illicit booze, and the western days began to slowly wane. The family purchased a major distillery in Quebec, along with many smaller distillers, and the centre of the Bronfman whisky world leaped far to the eastern hinterland.

But by this time, due to the inflow of massive amounts of Canadian booze to the U.S., the term “rye” had become fixed in the American mind as the same thing as Canadian whisky.

The word had been used by many Canadians as a synonym for whisky since the 19th century, when Canadian distillers began adding small amounts of rye grain into their wheat-based whiskies, and the name stuck. American appreciators of the Canadian-sourced water-of-life adopted the same terminology, and that has remained, 90 years since prohibition ended.

On the Prairies today, “rye” still tends to just mean any bar whisky you might mix with Coca-Cola to make a cocktail. It’s a permanent part of the prairie lexicon. Such rye-speakers might be surprised to find the term suggesting a different, higher-quality type of whisky when spoken by an American whisky tippler.

Few probably think, or even know, of the Bronfman connection to the word “rye” in the North American mind. Few think of Saskatchewan as a major player in the history of world whisky.

But at one time “Canadian whisky” turned a long swath of prairie towns and the centre of Yorkton into a land of dangerous opportunities, dangerous men and deadly business.

The trains roll past Bienfait today as they have for the century since Matoff was shot down a few feet from the tracks. Do they call his name with their mournful horns? No.

It is perhaps whispered in the wind, but for the locomotives, these southern towns and most prairie people, the memory of Matoff, the Bronfmans and the rest of that history mostly resides in echoes whenever somebody orders a rye and thinks that it’s just what you call whisky.