I’ve written many columns about China’s importance to global food trade and sometimes I think I sound like a broken record, but then I see a new statistic that causes my jaw to drop.

China’s grain and oilseed imports last year topped a staggering 167 million tonnes. Imports accounted for about 19 percent of its total annual supply (domestic production plus imports).

To put that in perspective, Canada’s total production of all grains and oilseeds in 2020-21, the year before the drought, was only 91.2 million tonnes.

It raises the question: are such huge imports sustainable for China, and for the world?

China has long been the world’s dominant soybean buyer and last year its soy imports actually slipped to 96.5 million tonnes from 100 million the year before.

But for decades it prided itself on being mostly self sufficient in grain and rice. However, last year it imported 65 million tonnes of corn, wheat, sorghum, barley and rice, up nearly 40 million tonnes from the year before and up almost 49 million from two years before.

Of that, corn was at a record 28.35 million tonnes, up 152 percent from the year before and wheat was 9.77 million tonnes, up 16.6 percent.

The soaring corn imports were partly the result of damage typhoons did to the Chinese corn crop in 2020, but that is not the only explanation.

After all, China’s government regularly boasts of record-breaking harvests. This December the national statistics branch said the annual harvest of all crops reached 683 million tonnes, up two percent.

Even with such increases, the vast grain stocks the country once held dwindled.

Not long ago the government changed policies to reduce what were considered excessive stocks.

One idea was to build up the corn ethanol industry to use the excess. But the policy worked too well, wiping out the stocks, causing domestic corn prices to soar, leading to the huge increase in imports.

A better corn harvest last year could moderate its corn and wheat imports this crop year, but even with bigger harvests, China’s demand for crops is outpacing the abilities of its domestic agricultural industry.

I have not yet mentioned the overwhelming shock that African swine fever dealt to China’s hog sector nor its inability to significantly increase its beef production.

Its livestock struggles have caused huge increases in meat imports.

In a country with shrinking agricultural land because of urban sprawl, severe pollution and critical shortages of water in many areas, expanding production is not a simple thing.

This creates vulnerabilities for its communist government.

Domestically, it would create unrest if it couldn’t meet the food needs of its citizens, and internationally it is weakened if other countries hold significant power over its food supply.

Every year the government holds meetings to discuss the food system and regularly officials trot out feel-good slogans about the importance of domestic food production and self sufficiency.

Past policies included campaigns against food waste.

But at this year’s meeting in December there seemed to be a greater urgency to the messages and commitment to change policy to boost domestic production.

Even before the meeting the Chinese government asked its phosphate and urea fertilizer makers to suspend exports to ensure an ample supply at home.

And this month it launched several initiatives designed to boost production.

Soybeans were the only major crop to see reduced domestic production last year, falling 16 percent as farmers shifted acres to more profitable corn. Imports always make up the vast supply of soybeans in China, but the government doesn’t want the shortfall to grow more. So, it announced an experiment of more than 2.24 million acres where soybeans and corn will be intercropped with the hope of lifting soy production without hurting corn bushels.

It has a goal of growing 23 million tonnes of soybeans by 2025, up 40 percent from the 2021 crop of 16.4 million tonnes.

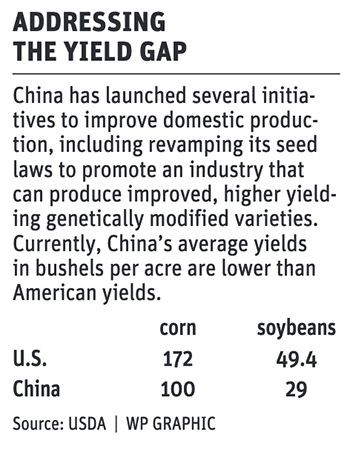

The government also rolled out new policies for its seed industry to speed introduction of improved varieties.

New rules about genetically modified crops and gene editing are expected to clear the way for commercial introduction and planting of domestically developed GM corn and soybeans that are insect resistant and herbicide tolerant.

Previously, China had approved GM corn, soybeans and canola for import but did not allow domestic production.

The government is also overhauling two huge state-owned agricultural companies, Cofco and Sinograin, to streamline the food supply chain.

News reports say part of the reorganization will be to shift crop trading and oilseed crushing assets from Sinograin to Cofco, allowing Sinograin to concentrate on managing its grain storage assets.

Will these initiatives bear fruit? Maybe, but it will take years and in the meantime, new challenges could arise.