Occasionally cattle have a reaction to vaccine. Most commonly, the reaction is mild, with local swelling and soreness at the injection site, but sometimes a reaction is serious and can be fatal if the animal goes into anaphylactic shock.

Dr. Andrew Niehaus of Ohio State University says anaphylaxis is a systemic reaction that affects the entire body. This type of reaction happens quickly, within a few minutes or sometimes up to an hour after the animal receives the vaccination.

Generally, the first sign of anaphylaxis is difficulty breathing, followed by collapse as the animal goes into shock.

Read Also

Mixed results on new African swine fever vaccine

The new African swine fever vaccine still has issues, but also gave researchers insight into how virus strain impacts protection against the deadly pig disease.

Vaccines contain specific antigens and their purpose is to stimulate the immune system to react and respond, and build antibodies to protect the animal later if exposed again to that disease antigen.

“Hopefully the reaction to the vaccine antigen will be mild and the animal never feels sick. But vaccine is designed to make the body react — to protect against the disease we are vaccinating for — and hopefully won’t create signs of illness. When we vaccinate animals, however, some respond a bit differently and may have an obvious reaction,” he says.

A few individuals are super-sensitive to that antigen, or sometimes sensitive to the adjuvant in the vaccine, for instance.

“In an anaphylactic reaction, all body systems shut down. The animal has trouble breathing and may experience cardiovascular shock and low blood pressure. The affected animal may collapse and lose consciousness, and may die quickly,” he says.

“More commonly, a reaction is simply some local swelling and inflammation at the injection site. This can happen not just with vaccine but from any kind of injection. Many animals have a local inflammatory response, which may produce scar tissue in that area.

This is why we see small knots or injection-site lesions, and try to avoid giving injections in the rump or any other areas that will eventually be high-quality meat. The scar tissue can usually be trimmed out, but we prefer to have that problem in a place like the neck, which isn’t such a valuable piece of meat. It’s not as great a loss if it has to be cut out when the animal is slaughtered.”

Another common problem, but not really a vaccine reaction, is an infection at the injection site. An abscess may result from an injection if the hide was dirty or a dirty needle was used.

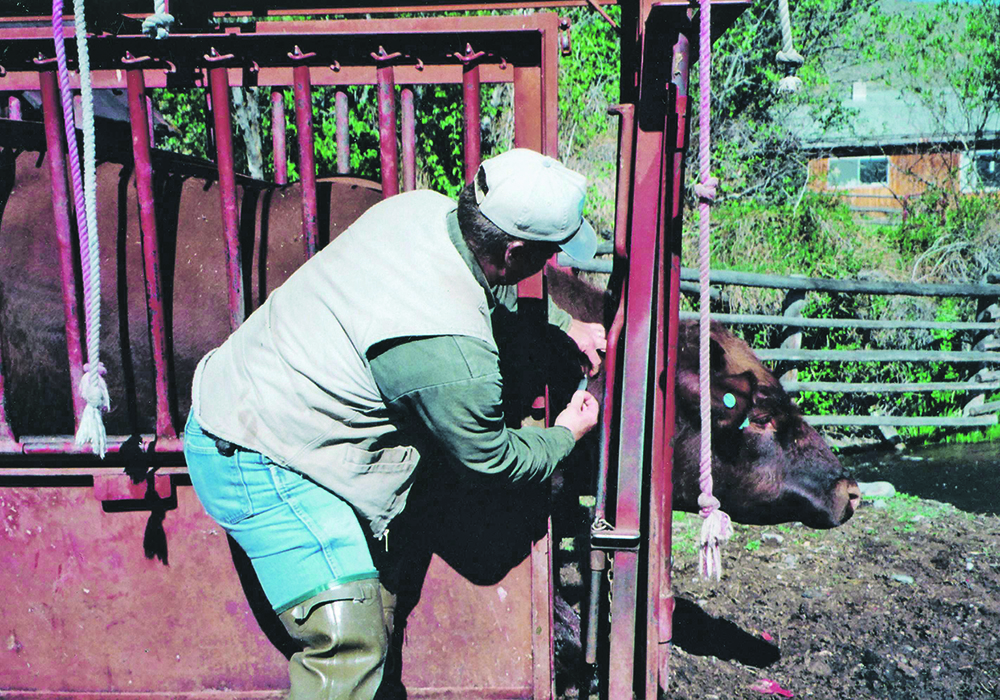

Most producers vaccinate their cattle annually or even twice a year, depending on the diseases in their region or on their farm. Some herds are vaccinated more frequently and with more types of vaccine than others. It is important to read labels and use proper dosage, proper timing for booster shots and the recommended injection sites. Some vaccines work best if given intramuscularly but most are now designed to be given subcutaneous — under the skin.

If an animal reacts adversely to a certain vaccine and survives, make note of that individual animal and consult with a veterinarian regarding future vaccinations.

If that animal ever experiences a second exposure to the same antigen, it may trigger a more severe (and possibly fatal) reaction. In most instances, the vet will recommend not vaccinating that animal again with the same vaccine.

Niehaus says it is also a good idea to contact the company that made the vaccine.

“It’s not so much to get reimbursed, but to let them know. They should be keeping records of any reported reactions. Vaccines are tested before they go to market, but the number of animals tested in clinical trials is nowhere near the number that will be getting the vaccine after people start using it. Knowing the true incidence of reactions (with large-scale use) are important for companies to know, and to keep track of,” he says.

Local swelling and inflammation generally do not need treatment other than time, but an abscess may need to be lanced and drained if it doesn’t break and drain on its own.

Anaphylactic reaction is much more serious, however, because the animal could collapse and die. Producers don’t have much time, but they might be able to successfully treat the animal if they have the proper antidote at hand when working cattle.

“When I am doing a lot of vaccinations, I usually have some epinephrine with me. This drug is a vasoconstrictor (constricting blood vessels). If the animal goes into shock, there is widespread dilation of all the blood vessels in the body (resulting in sudden drop in blood pressure).”

This drug can help constrict those vessels to help bring the blood pressure back up, and it also increases heart rate, which will also help increase blood pressure.

“This will facilitate better blood supply to all the body tissues. There are some other medications that will help, but the epinephrine works the best,” says Niehaus.

Steroids such as dexamethasone, used in conjunction with the epinephrine, can also be helpful. Antihistamine can be beneficial with a mild reaction (like a local swelling), but won’t be much help in an acute case of anaphylactic shock.

If an animal does go into shock, it is important to treat it with epinephrine immediately.

All vaccinated animals should be monitored afterward, for at least an hour.

Anaphylaxis can occur immediately or up to a couple hours after the vaccination, and there is more chance to save the animal with medication such as epinephrine and steroids the later it happens.

A person with only a few cattle may never see a severe reaction, but a producer with hundreds of cattle might experience this situation at some point.

“Serious reactions are rare, but if you process enough animals, sooner or later you will see a problem, so it would help to be prepared,” Niehaus says.

“There is some risk of abortion when giving certain types of modified-live vaccines like IBR-BVD. These problems are rare but we generally recommend not vaccinating pregnant animals with modified-live BVD vaccine because of this risk. Many of the newer products have a label for use in pregnant animals but you must follow the label instructions carefully,” Niehaus says.

If these animals have not been previously vaccinated and have no immunity, they would be at greater risk for abortion.

“The company will only stand behind a product if the label directions are followed explicitly. It will likely state that the product must have been used before, in those same animals, such as when they were heifers, before they were pregnant — with annual vaccination thereafter, so they already have some immunity. It is important to read labels and follow their directions,” he says.