Tony, Moira and Maxine are Lacombe pigs, a critically endangered breed that was the first strain of pigs developed in Canada.

The three “not so little” pigs were fondly named by Leah Predy from Ponoka, Alta., who decided to raise Lacombes after she moved back to the family farm, Halbern Farms, a few years ago.

“I just wanted to get a few pigs to raise up for meat. My mom kept suggesting I look for the Lacombe pig because my grandpa had had a few. He knew one of the people who helped develop the breed at Lacombe,” said Predy, who is an agrologist for an environmental consulting company.

Read Also

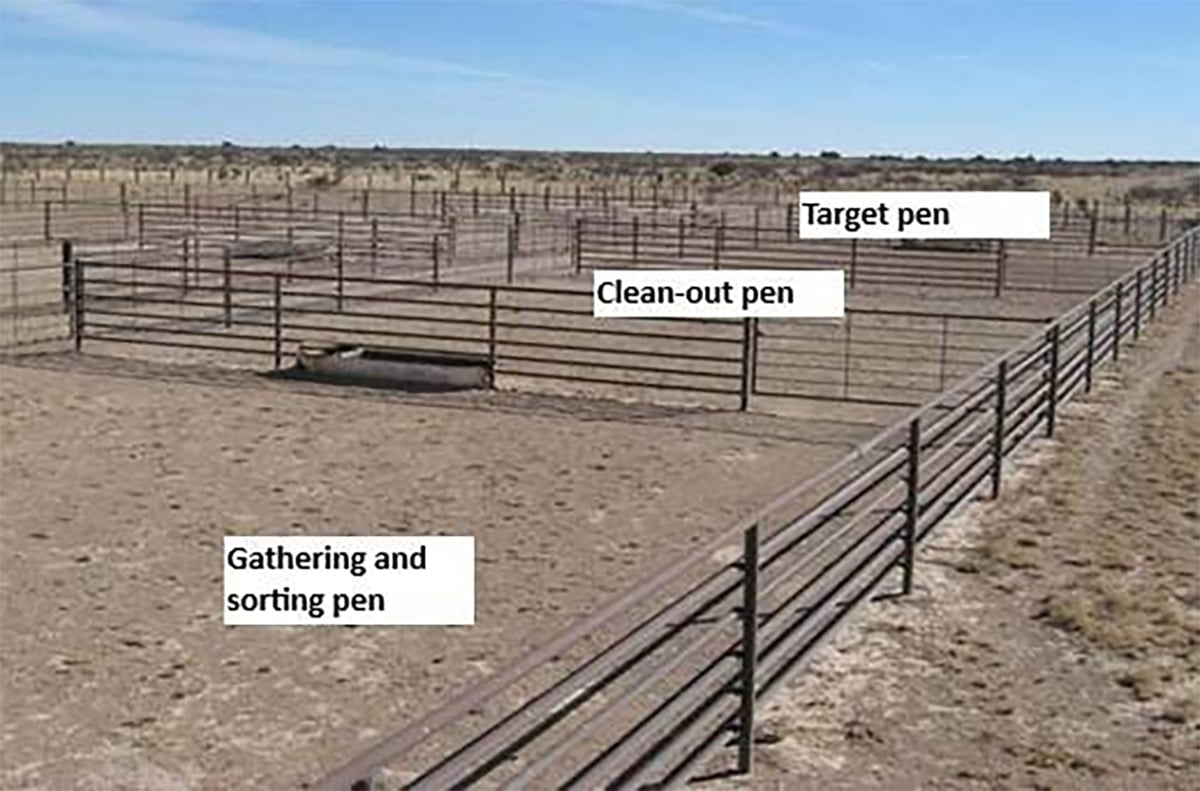

Teamwork and well-designed handling systems part of safely working cattle

When moving cattle, the safety of handlers, their team and their animals all boils down to three things: the cattle, the handling system and the behaviour of the team.

“So I started looking for them and quickly learned it was pretty hard to find them because they’re in critical condition because their numbers are so low.”

Fewer than five farms in Canada have registered stock so Predy, 32, is part of a small group focused on increasing the number of Lacombes.

Heritage Livestock Canada puts the current population of the species at 10 to 15 adult breeding females and two active breeding males. These numbers are so low, Lacombes are listed as being in danger of becoming extinct.

“We rescued them from one of the last two farmers in Alberta (who raised the breed.) And that was the population in the world,” said Elwood Quinn, livestock co-ordinator of Heritage Livestock Canada.

“We’re losing domestics 10 times quicker than in the wild.”

The breed was developed in 1947 and named for the Lacombe Research Centre in Lacombe, Alta.

With an eye on leanness, less waste and better feed conversion, the white, medium-sized pig with a docile temperament is a cross between Berkshire sows and boars of Danish Landrace and Chester White ancestry. The goal was to produce a pig that could be crossed with Yorkshires, the dominant breed at the time.

They were specifically bred to be raised in confinement as dedicated hog barns began to proliferate.

Known for great taste, texture and colour, the popularity for Lacombes took off after they were commercially introduced to pork producers in 1957. The breed reached about one million animals during the 1960s and ‘70s, said Quinn.

“That’s when they shone. They were showing at the Royal Winter Fair in Toronto and did very well. They did well in what used to be carcass exhibitions, which doesn’t exist anymore in Canada,” he said.

Lacombes are the fifth-ranked breed of swine in Canada. Some 1,743 animals were registered in 1981, which included 648 boars and 1,095 females.

“It’s probably the nearest thing in heritage that matches what is now the market standard for hogs. That, I think, is a phenomenon that tells us how good our researchers were back in the 1950s to put this together, that the quality of it and the result of its production is so similar to the commercial hog of today’s market,” he said.

Quinn said genetics, proprietary breeds, barn production methods and marketing played a large part in the Lacombes’ eventual collapse.

“It’s a factor of commercial agriculture. It’s a factor of consumers demanding everything will be exactly the same — 99 percent of our consumers. The other one percent will look for a unique product,” he said.

“(Lacombes) were just way ahead of their time in their efficiency, the activity of them on the floor in a hog barn and the industry caught up to them … passed them, looking for even leaner. But today’s modern pig is so lean, the flavour is missing. So this animal brings back some of the flavour and appearance and texture,” said Quinn.

Predy and her mother, Mary Ann, are both perplexed by the Lacombe breed’s endangered status. They say the pigs are good-natured.

“They’re fairly placid. They make pretty good mothers. I don’t know why people didn’t cotton on to them,” said Mary Ann.

However, large droopy ears might be one reason.

“I think part of it was their floppy ears used to get bit a lot in confinement and they’d swell up,” she said.

Long in body, the pigs grow to a length of about 4.5 feet with short legs and a meaty conformation.

Mature boars average 650 pounds, sows 500 lb. and a typical litter is between 10 and 12.

The Predys house their Lacombes in the old commercial hog barn that sat unused for years before Leah’s return. The barn now doubles as a lambing centre.

Following the same path as her parents and grandparents, Leah has found names for some of the animals she said have standout personalities.

“When you’re only feeding six or whatever every day, they develop a personality and you get a bit of a connection to them,” said Leah.

The small group of pigs now includes a registered breeding pair, registered gilt, three unregistered sows, an unregistered gilt and several litters of unregistered piglets that will be sold for meat.

Their first litter of registered piglets was born in May and they’re expecting a second in September.

“That’s been very promising and I’m keeping one of the registered gilts from that litter. So I’ll have two registered sows — two registered females to continue breeding,” she said.

Word of her venture is slowly spreading and genetics for the heritage breed are on the move again.

“I just sold a boar and a gilt to a farm in B.C. and they got some pigs from out east as well. I’ve got some interest from a couple of farms in Alberta and there’s some in Ontario, Quebec and Saskatchewan,” Leah said.

“I think the interest is gaining, so hopefully we can all make a go of it. It’s really small farms that are the key to these.”