Productivity and yields are rising, along with costs and greater expectations for environmental controls. How can farmers navigate?

Over the past few decades, grain and oilseed producers in Western Canada have made consistent gains in farm productivity.

But can upward yield trends be sustained in an environment where public policy discourages fossil fuel consumption and increasingly views the use of commercial fertilizers as a culprit contributing to global climate change, rather than a valuable input that helps to feed a growing world population?

These are important questions that will shape society’s views of global sustainability.

They are also questions that resonate with farmers here on the Canadian Prairies.

Read Also

Potato farm requires year-round management

The most recent Open Farm Day in Alberta showcased agricultural producers across the province educating the general public about the process that is required is to get food to their table.

Statistics acquired by The Western Producer show that average yields for major field crops have increased significantly since the early 1980s.

According to historical yield data from provincial and federal government sources, Saskatchewan’s average yield for barley increased from 46.98 bushels per acre in the early to mid-1980s, up to 66.24 bu. per acre currently — an overall yield increase of 41 percent over 40 years.

Yield data from the 1980s was calculated based on a five-year average of all Saskatchewan barley yields over a six-year period from 1982-87, with the lowest production year (1984) excluded from the calculation as an outlier.

Current yield data used a similar calculation model, assessing average provincial yields from 2017-22, with the lowest production year (2021) excluded as an outlier.

The same calculation model revealed a consistent upward trend in average provincial yields of all major crops, including wheat, canola, oats and peas.

In canola, Saskatchewan’s five-year average yield in the early- to mid-1980s was 23.92 bu. per acre, government data show.

That average rose to 40.66 bu. per acre in the five-year period from 2017-22; an impressive 69.9 percent average yield increase over the past four decades.

Average oat yields rose from 54.52 bu. per acre in the 1980s, up to 93.04 bu. per acre currently, an increase of 70.6 percent.

And five-year average yields for spring wheat rose from 28.32 bu. per acre in the 1980s, to 48.12 bu. per acre currently, an increase of nearly 70 percent.

In that context, the contributions of Western Canada’s farmers to global food security are unquestionable.

There is little doubt that upward yield trends over the past four decades have contributed to a western Canadian ag sector that is better capitalized and more profitable.

Today’s agriculture industry is more productive, more resilient and more economically sustainable than it was in the 1980s, a period defined by extreme drought in many parts of the West, generally poor market returns, high and persistent unemployment rates and steep borrowing costs, typically in the range of 10 to 20 percent.

Mortgage rates in some Canadian markets surpassed 21 percent in late 1981.

According to experts, yield gains realized since the 1980s were based on many factors, including declining interest rates, better capitalization in the ag sector, investments by farmers, governments and private sector partners in plant breeding and field research, and the commercialization and adoption of new products developed by industry partners in the technology and life science sectors.

The widespread adoption of improved farming practices — practices that are less reliant on fossil fuels and more focused on maintaining healthy soils — also played an important role.

Today, mechanical tillage on Western Canada’s conventional grain farms is all but extinct and production risks associated with soil erosion have been reduced significantly.

The widespread adoption of no-till production by Saskatchewan’s agricultural producers should be recognized, say soil conservationists and other ag industry stakeholders.

“The carbon sequestered each year by Saskatchewan farmers is a critical asset to help both the federal and provincial governments meet their climate change goals,” said Jocelyn Velestuk, a Saskatchewan farmer and director at Saskatchewan Soil Conservation Association, in a recent SSCA news release.

“Each year, through no-till practices, Saskatchewan farmers sequester about nine million new tonnes of carbon dioxide. We are committed to achieving a regulatory environment that recognizes this significant positive impact.”

Indeed, today’s producers are more mindful than ever about the need to protect the environment while increasing yields and productivity.

But despite their impressive yield gains, and simultaneous reductions in fossil fuel use and soil tillage, Saskatchewan’s farmers face new challenges that could jeopardize future yield improvements.

Ottawa’s vague and poorly defined commitment to reducing emissions from agricultural fertilizers is a case in point.

The federal government has indicated that it would like Canada’s farmers to reduce fertilizer-related greenhouse gas emissions by 30 percent by the year 2030.

Ottawa did not yet indicated how growers should reach this target, or whether the target will be mandated.

Without any clear guidance as to how such a goal will be achieved, ag industry stakeholders already impacted by the federal carbon tax have expressed concern that Ottawa might unilaterally mandate a 30 percent reduction in fertilizer use.

A few months ago, officials with the Alberta Wheat Commission (AWC) weighed in, suggesting that an absolute reduction in fertilizer use would have a “catastrophic impact” on farm productivity and profitability.

“I think we’re still trying to understand the government of Canada’s intent on this, as to whether or not it’s an absolute reduction (in fertilizer use) or an emissions reduction target,” said AWC general manager Tom Steve, when asked about the emissions target.

“We’ve had a lot of discussion on this topic but obviously, if farmers are required to reduce their fertilizer use by 30 percent by 2030, that would have a catastrophic impact on yields and competitiveness.”

“You know our arguments by now,” added Gunter Jochum, president of the Western Canadian Wheat Growers, in a recent message to members.

“Canadian farmers are already among the best in the world at efficient fertilizer use and a mandated cut to fertilizer will mean lower yields, less food, and higher prices.”

In a recent address to the House of Commons standing committee on agriculture and agri-food, Jochum told federal politicians that federal efforts to reduce fertilizer use would contribute to supply chain disruptions and would fuel concerns over global food insecurity.

With mandated restrictions on fertilizer use, “a major supply chain disruption will begin at the front end — right in our fields,” said Jochum, a Manitoba producer.

Jochum said he is optimistic that Ottawa will not impose a mandated fertilizer reduction. Instead, he believes Ottawa will work with the industry to achieve emissions reduction targets that do not involve absolute fertilizer reductions.

“The government’s language (has) evolved to it being a voluntary target and they’re looking at making current efficiency methods count towards the ultimate target,” Jochum said.

“That’s a huge difference. If the government wants farmers to be more aware of the need to limit fertilizer use, fine, we’re on board. A mandated cut on the other hand, might be met with (resistance).”

“We will continue to monitor and observe, and we will be ready to use our resources and voices to shout at the top of our lungs should the government show any sign of moving toward a regulatory direction.”

Saskatchewan premier Scott Moe has expressed similar concerns.

With a zero-till adoption rate estimated at 95 percent, Moe said Saskatchewan’s agricultural lands are fixing so much carbon that they should be considered net negative in terms of greenhouse gas emissions.

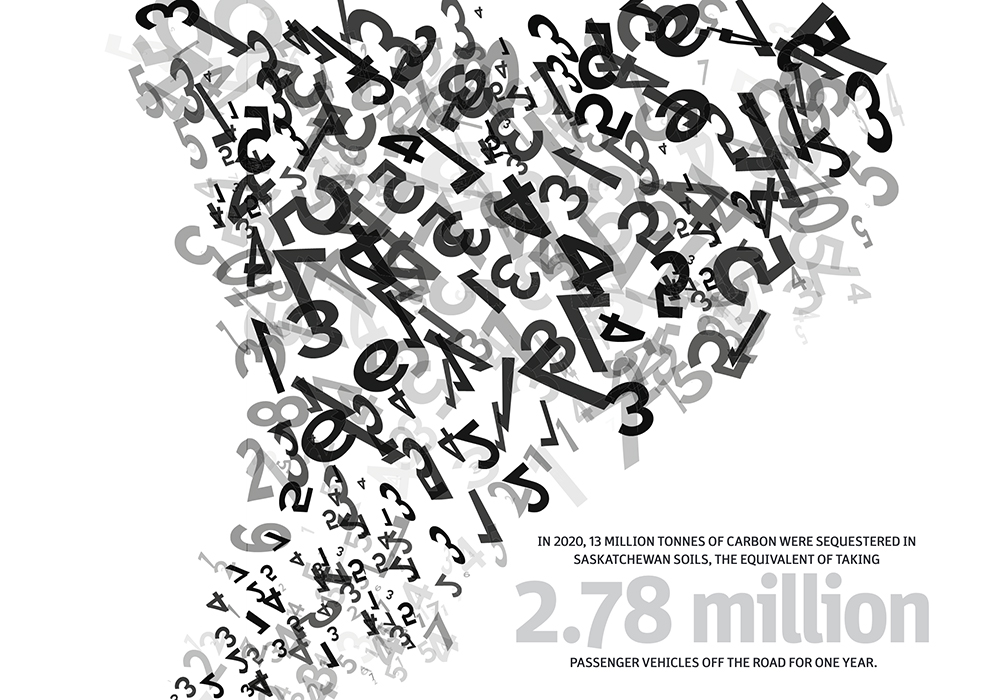

In 2020, about 13 million tonnes of carbon were sequestered in the province’s agricultural soils, Moe suggested.

That’s the equivalent of taking 2.78 million passenger vehicles off the road for a full year.

“My government will continue to ensure our producers have every opportunity to reach maximum production in a sustainable manner,” Moe said

On Nov. 1, the Saskatchewan Party introduced the Saskatchewan First Act, provincial legislation aimed at protecting the province’s future economic growth from what the province’s justice minister Bronwyn Eyre called “intrusive federal policies.”

“We’re concerned that as in so many areas — methane, clean electricity regulations, the carbon tax — it very, very, very quickly becomes not a partnership of equals… but a dictation about compulsory measures, which absolutely harm the province and the ag sector, which is the most sustainable of any ag sector in the world,” Eyre said.

“We’re concerned about the signals that are being sent about the fertilizer reduction and potential mandates in that area,” she added.

The Saskatchewan First Act would confirm the province’s jurisdiction over activity in various sectors of the province’s economy including natural resource extraction, conservation, forestry and electrical generation, Eyre said.