LUNDBRECK, Alta. — The red bandana across Joe Guy Brewer’s face is a solitary spot of colour against the blacks and whites and browns of southern Alberta after a snowstorm.

Even his horse is black and white. It’s a horse with no name that was facing a trip to the meat plant only one month ago.

Snowflakes flash in emerging sunlight as the Australian cowboy dismounts and shakes snow from his leather clothing. He’s nearing the end of a 700 kilometre trip along the cowboy trail, a scenic stretch of road that runs along the mountains and foothills of the Rockies.

Read Also

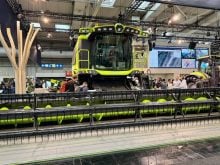

Agritechnica Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year

Agritechnica 2025 Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year.

Brewer is limping as he walks into O’Bies General Mercantile and pours himself a cup of tea. He adds five creams.

“I stepped on something in the bush yesterday,” he says in explanation. “I’ll have to wait for it to fester and then pluck it out.”

The six-foot-tall cowboy smells like smoke and wet leather. His hat has a round hole in the crown. It’s not from a bullet, he says in answer to queries, but he doesn’t seem surprised at the question.

He’s been sleeping on the ground and in barns and old buildings since undertaking this journey Nov. 3. Gale force winds and -22 C temperatures have punctuated his days.

The ride is one of many for Brewer. He has ridden thousands of kilometres on horseback, but this particular trip is a rescue and training mission for the horse he is riding — the horse with no name.

The mare belongs to Dodie Greenwald, a rancher near Fox Valley, Sask., who was ready to give up after three different trainers failed to tame it for ranch work.

“I didn’t want to stick any more money into her,” says Greenwald. “There’s only so much money you can pour down a horse before you go, ‘I give up.’ And that’s the state I was at. The next step was the canner.”

Then she came across Brewer. “I save lives, is what I do,” he says. “I save horses from getting their heads cut off and I save their owners from breaking their necks.”

After teaching a horse training clinic in Saskatchewan, Brewer offered to ride Greenwald’s horse during a planned trip down the Cowboy Trail.

“It sort of gave me a chance to get away from the wife and kids for a month,” he says with a wry grin.

And the horse with no name is working fine. The previous day, Brewer used it to help a rancher move cattle in the Porcupine Hills.

“For me, it was a challenge of one horse, not lamed up, never worked a day in its life, and 700 kilometres later, it hasn’t got a mark on its back, it hasn’t got a sore foot, it’s got no scratches on it. The horse is in perfect condition.”

It is one of hundreds of horses he has trained in Australia, the United States and Canada over the past 20 years.

“I haven’t had a horse in all my life I couldn’t fix,” Brewer says between sips of tea. “I’ve had some good ones that I’ve stayed awake thinking about at night, but I haven’t had one yet I couldn’t fix.”

How?

“What I do is capture the mind, and the horse gives me the body.”

As a songwriter, author, actor and promoter, such statements come easily to Brewer. His personal philosophy involves belief in individual purpose and belief that fate brings people together when the time is right.

He ran away from his Australian home at 12, lived on the street and drifted into drinking, drugs and theft. It was a grim life, he says.

“At 19, I went looking for my purpose in life on the back of a horse. Took a rifle, shot my food for two years, travelling across the outback of Australia. Went from job to job. I

worked on some of the biggest properties in the country.”

Over time, he found music, became a street performer,

managed nightclubs and built a restaurant. All of it had a common thread.

“Every job I’ve ever had, a horse has taken me to it. I went looking for my purpose in life on the back of a horse and then found it was a horse. So now I sort of spend my life saving them.”

Brewer describes himself as a horseman but also a motivator. He says he tries to inspire through his music, his books and by talking to people on his travels.

And he meets many. On this trip he met a producer who seems interested in building a reality show based on Brewer’s activities. That’s one of the reasons he has a video camera mounted on his hat and is equipped with a cellphone.

Welcome to the new west. The old west and the romance of the lone cowboy on the trail are gone, Brewer says.

But he offers no nostalgia. This is the new reality.

“I try to keep it as real as I can. I try to meet as many people as I can. I’m not that solitude cowboy that wants to just ride the mountains. If I did that, I couldn’t save horses and meet people and inspire people with my story.”

Brewer says there’s a spiritual aspect to his long rides and his contact with people, though not in the conventional sense. He does his soul searching on trips like this and believes he connects with certain people for a reason.

“Sometimes you can tell that they’re looking for something and not sure what it is.

“Sometimes I feel like I might have something to share with them, so I share it with them.

“I always say you plant a seed, water it and walk away. It will grow if it’s meant to. Maybe somebody else will come along and water it. Who knows?”

The horse with no name has no bridle, only a halter of Brewer’s invention. It stands still as he mounts up and ties on his bandana as protection against chinook winds.

The next purpose in life awaits.