A teenaged farm boy from Manitoba uses an icy adventure in the mid-1970s as a way to test himself against the elements

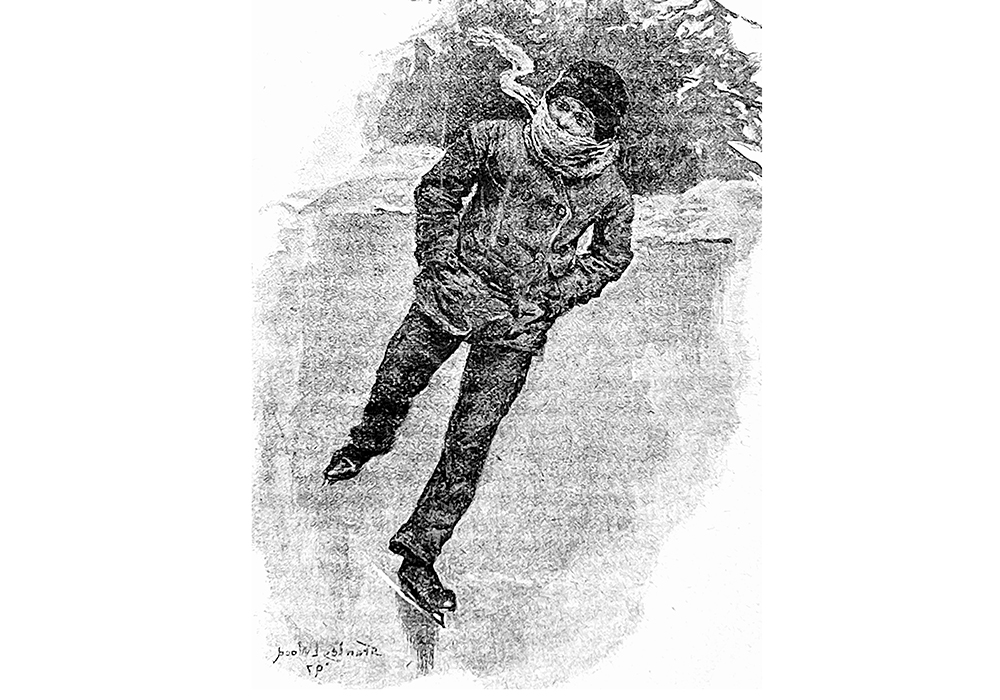

It had to happen. Combine a mile-long lake, glazed wind-buffed ice, a cold prairie wind and a moonlit surface and for one evening in December 1976, Manitoba had its own Hans Brinker.

The fictional young Brinker skated the canals of Holland in a bid to win the “Silver Skates” prize. I skated the lake’s length with my almost new hockey skates. My prize at the east end of the lake was the hamlet of Basswood, Man., with its post office.

My purpose? I told my mom that I would pick up the mail. However, the larger goal was to test myself, as older teenagers must.

Read Also

Farm equipment dealership chain expands

This summer, AgWest announced it was building two new dealership buildings in Manitoba to better service its expanding market area — one in Brandon and the other in Russell.

Could I skate the two-mile round trip in the cold of a winter evening, do a short hike on each end, and return with a packet of Christmas mail for Mom — and with bragging rights to my three farm boy brothers? I had to try.

Winter had come early and the stagnant lake had been frozen for almost two months. Dad had to chop the ice deeply for the cattle’s watering hole. A dusting of snow had covered the lake, but one evening, a western wind suddenly polished the surface.

It was time to enact my plan.

I spilled out my idea to Mom, and although not entirely in favour, she seemed to understand. She didn’t mind, either, that I would empty the mailbox, housed in Menzie’s Hardware Store. She loved receiving Christmas cards (and still does) and responding.

However, mothers tend to worry when their 16-year-old sons “feel their oats” and seek to test their limits, so she quietly brought Dad into the picture. They decided that I would have three hours for the sojourn, and after that, they would dispatch older brother David with his Skidoo to follow my route across the ice.

I would have to dress extra warmly in my farm chore clothes and promise not to stray from my described route. I promised.

When I saw the wind-swept ice surface, I knew this was the time. No more lame excuses of fatigue, cold, darkness or skates. I had bought almost-new blades that fall.

The cliché applied and I used it for motivation: it was now or never.

After the farm chores Dec. 20, I zipped into the house, grabbed the mailbox key, a large bag and a piece of twine, and slung my skates over my shoulder. A younger brother, Tim, noticed the skates and sensed something was afoot. We never went alone to skate on the dugout rink.

“I’m skating to Basswood to pick up the mail,” I said nonchalantly. He was speechless. Good. I was three years older and now I could prove I could best him. I closed the house door to light, warmth and security.

Soon I was at the edge of the rink lacing up my skates, now with my farm boots slung over my shoulder and secured with the twine. It was cold, maybe -10 C, but Mom had reminded me that I would keep warm if I kept moving.

I began to wiggle my fingers inside my mitts and took my first stride. Whoosh!

A soft wind from the west propelled me. The ice was like glass. The half-moon light shimmered, and in the distance I could already spot a Basswood beacon — maybe from the top of the grain elevators. I churned my legs faster.

Inadvertently, I had created my own windchill. I pulled my scarf up over my nose and pressed on.

The evening was quiet, silence interrupted only by my skate blades slashing against the frozen water. Usually at our farmhouse, I could hear winter noises: an owl hooting, a neighbour’s dog barking or a calf bawling. But out here, I heard only the sound of silence.

I settled into a skating rhythm, even clasping my hands behind my back like the Olympians did. Soon I was behind the Basswood garbage dump and bearing down on the hamlet streetlights.

The Basswood Cemetery slipped by to the south. The wind, interrupted by a curve and trees, still pushed. My strides lengthened. Mr. Brinker, real or fictional, would not have kept up.

Bobby Orr would have passed me, though.

I put on the “brakes” at the Basswood shore. I had made it — at least one way.

I changed into my boots, which were oh so cold and began the five-block trudge to the post office, clunking along the abandoned winter streets. A few Christmas lights twinkled among the houses.

The small post office lobby was open. I fished the key from my coat pocket. A packed Box 107 spilled mail onto the floor.

With the letters in a large puffed-wheat bag and the twist tie secure, my “turn-around” was done.

The skates, stashed in a snowbank, were cold but my heart was warm. I knew I had met this challenge and I knew how thrilled my parents would be as they sorted through the bag of Christmas mail.

Mom and Dad had lived in Steinbach, Man., Russell, Man., and Dryden, Ont., and had friends and relatives in all those places. Long before any internet, their once-a-year letters came at Christmas time.

With a few strides, I was moving fast and easily followed my previous ice slash marks under the light of the moon. Soon I was back to our hockey rink at the dugout and turned an extra circle just to lose some speed.

At the porch door, I glanced over the winter world one more time: cold, bleak and colourless. Three steps later, the inside of the farmhouse was the opposite — plus the joyous noise of brothers and parents. They abandoned Lawrence Welk on TV.

I produced the bag of mail. Mom was pleased and but happy too that her son made it home safely. Dad said it had taken me only two hours.

As for my three brothers, they were stunned at my feat. Tim still remembers it 45 years later.

And Hans Brinker? He would have taken second place, behind the Manitoba farm boy.