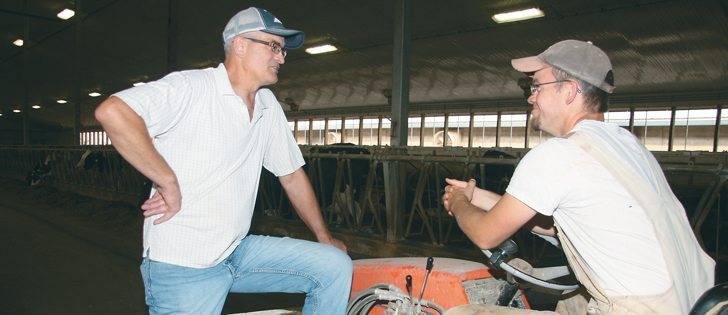

CARONPORT, Sask. — Farm labour is less of a problem at Caron-crest Farms Dairy, thanks to the many students housed across the Trans-Canada Highway at the Briercrest Bible College.

The McLeod family farm straddles the highway, with their pastured Holstein cattle ambling through a tunnel that links fields on either side of the road.

The central Saskatchewan location means employment opportunities for students, say farm owners Blaine and Marlie McLeod.

The couple, with their sons, Mark and Michael, manage the dairy’s 320 milking cows and 2,500 acres of feed crops and pastures.

Read Also

Fuel rebate rule change will affect taxes and AgriStability

The federal government recently announced updates to the fuel rebates that farmers have been receiving since 2019-20.

In addition, they employ three full-time workers and many part-time students.

“You’ve got to put your trust and faith in the employees who do the work for you,” said Blaine.

Marlie, who handles human resources for the operation, said they look for workers who are willing to work early and late shifts, show initiative and have an appreciation for livestock.

The farm location makes it easy for the many trucks coming and going.

“It’s a terrific location on the highway. We are too visible so vandalism is not a problem,” Blaine said.

However, vehicles sometimes careen off the highway into their pastures.

Marlie feels the family has had the best of both worlds, living in nearby small towns and running a farm business.

“I love the farm lifestyle. Wherever (Blaine) is, that’s where I am. We do it together,” said Marlie.

“They (the children) can see what it takes to run a farm business, see Dad putting in long hours.”

The family comes together for business meetings, with Marlie and Blaine overseeing bookkeeping and finances, Michael acting as herdsman in charge of breeding and feeding and Mark doing fieldwork, maintenance and animal husbandry.

Mark and Michael, whose wives are both school teachers, each have one child. Michael studied music at Briercrest and played in a band before studying animal science and working at another dairy.

“Dad said to go away and work for someone else, get an education,” Michael said. “I played (music) semi professionally but it wasn’t near as much of a guarantee.”

He has seen many changes to the operation since his father took over from his father in 1981.

“Change is inevitable, growth is optional,” he said.

“Nothing will stay the same.”

They built a modern barn with venting windows and high ceilings and grew from a double six to a double 12 parlour where they milk twice a day. The herd is principally Holstein, although Blaine also keeps a few Jerseys.

“I knew I wouldn’t stay in the industry if I didn’t do something better,” Blaine said.

“With the growth in the herd and lots of hours spent milking, we felt if continuing to grow, we would make it easier,” Blaine said.

Michael is open to incorporating new efficiencies.

“You have to have your eyes open to opportunities and work with your asset base,” he said.

“You have to make sure the basics are covered and be organized.”

Blaine said their “sandy piece of land” has benefited from injecting manure back into the fields.

Animal welfare and economics are also top of mind. The farm maintains good sanitation and herd health with vaccinations, keeping cattle tails and hooves trimmed, washing down alleys and maintaining biosecurity protocols.

“There’s a lot of attention to a lot of little things,” Michael said.

“If you look after the cow well and give her a clean, safe environment, she will milk well, last longer and be productive,” said Blaine.

Many look over the fence with envy at the regular pay cheques of dairy farmers, but the family said it’s hard work and long days.

“Some think it’s a licence to print money but it’s not. If you’re not looking after it, it goes down hill quickly,” Blaine said.

He questioned the wisdom of changing supply-managed systems in trade talks.

“We can produce milk cheaply elsewhere, but do we want that or do we want safety and security, with government regulations in place?” he said.

For dairy farmers, the regular income means the opportunity to do long-term planning and investing.

“It provides some stability that the end product will be profitable,” said Blaine.

He said their income comes from the marketplace rather than subsidies, which are prevalent in many European countries.

Blaine sees the local food movement as a positive trend for the dairy industry.

Michael would like to see dairy quotas proportionately linked to local markets, noting how Ontario and Quebec farmers produce more milk than they have the market for.

The family also believes in transparency and education, with Marlie involved in agriculture in the classroom and hosting free tours through their operation.

She said students ask questions such as why dairy cows are skinnier than beef cattle, how milk goes from the cow to the container and how much milk one cow produces a day.

“We need to be open to people seeing where food is produced,” said Blaine, who was the first chair of Saskmilk.

“If you are a dairy farmer, that defines what you do. There’s a lot of pride that comes with that.”

The farm has been challenged this year by high feed costs, as much as $250 to $300 per tonne compared to $120 in past years.

Michael said that requires more creativity with rations and looking at options while still working closely with feed nutritionists.

For the future, the family is eying more changes, including upgrading the milking system within two years and replacing an aging barn.

Contact karen.morrison@producer.com