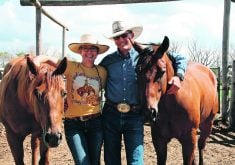

On the Farm: Livestock help remove some of the risk from grain farming, but family says the animals also make them smile

WADENA, Sask. — Charlotte Schwanke remembers exactly what happened 13 years ago on Jan. 16, 2009.

It was a special day because her fourth child, Ephram, was born in Regina.

The birth of a child is definitely memorable.

But what’s really burned into her memory is something her husband, Dale, said and did on that day.

Ephram was breached, so the doctors turned him around and induced Charlotte into labour.

Dale was nervous and couldn’t wait at the hospital any longer. So, he left the building to find something to read. He bought a Western Producer at a nearby store, opened the paper and quickly noticed an advertisement for land.

The Schwankes’ farm is northeast of Wadena and a parcel of land was for sale, right next to their property.

After reading the advertisement, Dale marched back to the hospital and into his wife’s room.

He had made a decision.

“He announces this to me (while) I’m contracting and in labour: ‘we’re going to buy some land’,” Charlotte said, sitting at her kitchen table and recalling what happened. “It’s a crystal-clear moment in my mind, still.”

Charlotte forgave Dale for his mixed-up priorities in that moment, possibly because she’s equally committed to their farm and the decision to buy the land was a good one.

It allowed the Schwankes to expand, giving them enough land to add sheep to what was a grain farm. They now have 150 ewes and sell lamb meat to restaurants, retail stores and direct to consumers across Saskatchewan.

Their website, redbarnfamilyfarm.com, says they supply some of the top restaurants in Saskatchewan with lamb, including Hearth Restaurant in Saskatoon and Mabel Hill Farm Kitchen in Nipawin.

Their children are also in the farm to fork business.

Madeline, 18, is the sheep expert in the family, who knows all the ewes and their offspring. Blake, 17, raises chickens and manages beehives. Robyn, 16, produces turkeys and Ephram, 13, raises pigs.

Charlotte’s 17-year-old nephew, Ben, also lives on the farm.

All of their products, including lamb meatballs, lamb sausage, lamb chops, other proteins and honey, are available for order on their website.

“I think we’re the only place in Saskatchewan (with) this many (lamb) products,” said Charlotte, who grew up on an acreage near Regina and studied interior design in Calgary.

She met Dale in the 1990s while he was in Saskatoon, earning his ag diploma at the University of Saskatchewan.

Dale grew up on the family farm, about 30 kilometres northeast of Wadena. He was the youngest of four kids and the only boy. Dale always knew he would take over the farm from his dad, but it happened sooner than expected.

His father passed away when Dale was 13 and he started running the farm as a teenager.

While at the U of S, Dale became friends with Charlotte’s brother, Mark.

“Dale was the only guy that my big brother said I was allowed to date,” Charlotte said with a laugh.

Her brother had good instincts, as Dale and Charlotte became friends and then started dating.

They married in 1999 and began farming together. Grain farming wasn’t easy in northeastern Saskatchewan for much of the 2000s, because the growing seasons fell into three categories: wet, wetter and wettest.

“We had a couple years where we had seeded exactly zero acres because land was inaccessible and beyond saturated,” Charlotte said.

One year they seeded canola from an airplane, hoping something would grow. Another year they tried fall-seeded crops.

“We had years where harvest didn’t start until October or November. We had days where we pulled the combine out of mud three … four times.”

To pay the bills, Dale had a seed-cleaning plant in Kelvington, Sask., and Charlotte worked as an interior designer. She was employed at firms in Regina and Saskatoon, then started her own business.

“I designed the house next door and a lot of other things in the area,” she said at the kitchen table of their farm, with her back to a five-by-three-foot map of the world, framed on the wall.

The Schwankes frequently use the map because their kids are home-schooled. It’s useful to point to the map when teenagers have questions about Vietnam or what happened during the Second World War.

Eventually, after years of soaked fields and poor yields, Dale and Charlotte realized that grain farming was too risky. They considered adding sheep to the farm many times, but hesitated because children occupied most of their time.

“We were so involved with having little kids and trying to stay afloat with the grain farm,” Charlotte said.

Sheep became more realistic in 2009, after they bought the additional land. Finally, in 2012, the Schwankes got their first flock when they purchased seven sheep from a friend.

Immediately, they knew it was the right decision.

“We loved it, from the moment it started. (Now) every spring my favourite thing is lambing,” Charlotte said.

Dale was also charmed by the sheep.

“I’ve never been disgruntled when it’s time to go feed them…. I bang on the pail and they’re going to come running, and it just makes me laugh,” he said. “The barley in the bin never gave me that kind of feeling.”

The sheep, though, are more than fun.

The lambs from their farm are processed at Wadena Meat Processors, a provincially inspected plant, and the meat is made into an assortment of products. One of their signature items is shishliki, marinated cubes of lamb usually cooked on a barbecue, a popular dish in northeastern Saskatchewan.

“Our local historians indicate shishliki originated during the war times in Russia,” says the website for the town of Kamsack. “Along their travels they would ‘borrow’ a lamb and marinate the meat to preserve it. Shishliki is a huge part of our local sports day events in our communities. The recipe is passed down through the generations.”

By selling lamb directly to retail, restaurants and consumers, the Schwankes have stabilized their income and made their farm more viable.

“We’re trying to have a diverse group of buyers,” Dale explained. “The whole point is to have a revenue stream, every month.”

The Schwanke farm is about 250 kilometres from Saskatoon and a similar distance to Regina, but they’ve succeeded in selling their lamb products to urban customers.

That’s partly because Dale enjoys cold-calling chefs and other buyers to tell them about the sheep and the farm.

Part of the sales pitch focuses on the breed of sheep. The Schwankes raise Katahdin sheep, a breed named after a mountain in Maine.

“They’re a hair sheep, so they shed… They don’t need to be sheared,” Dale said.

“Because they’re hair sheep they don’t have lanolin, which is the stuff in the wool. (That) is where you get that tallowy taste (in the meat)…. So, they are much more mild (in flavour).”

Looking forward, Dale and Charlotte plan to expand their flock of sheep, but they haven’t decided on how much to expand. When they do get larger, there will likely be strong demand for their products because Canada needs more lamb production.

Right now, Canadian farmers produce only 40 to 45 percent of the lamb consumed in the country.

There is an opportunity to grow their business, but the Schwankes still want to enjoy what they do. Part of the fun is giving names to all their sheep.

Every year, using the letter of the alphabet designated for tags that year, their sheep get names starting with that letter.

“We always joke that we’re terrible professionals because all our sheep actually have names,” Charlotte said.

Naming sheep may be silly and a throwback to a time with smaller farms, but maybe the Schwankes have it right. Raising livestock and making money from a sheep called Fiona is probably more fun and satisfying than feeding and raising F-36.