MINNEAPOLIS — Mars has a problem.

Not the red planet, but the company.

It’s one of the largest human and pet food companies in the world, posting $50 billion in revenue last year.

Read Also

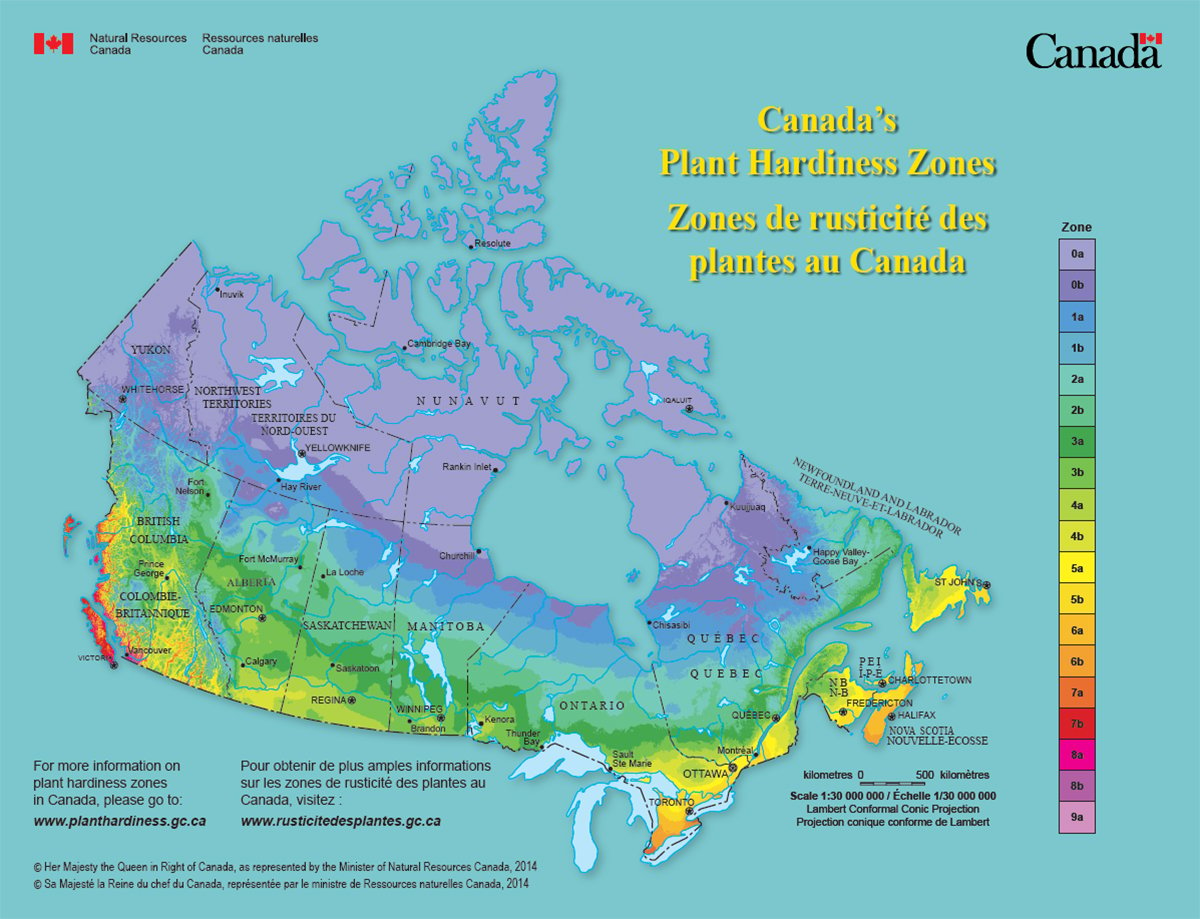

Canada’s plant hardiness zones receive update

The latest update to Canada’s plant hardiness zones and plant hardiness maps was released this summer.

Related stories in this issue:

- Regenerative agriculture resumes bottom-up approach

- Road to sustainable food systems needs patches

- Producers lose their climate villain reputation

Global sales have been increasing, and this year the privately held company acquired the Kellogg’s line of breakfast cereals.

The financial returns and recent expansion are positive, but Mars Incorporated has a sustainability problem.

It has committed to cut its greenhouse gas emissions 50 per cent by 2030 and reach net zero in 2050.

Achieving its 2030 target could be difficult (maybe impossible) because about 96 per cent of its emissions are Scope 3. That means the greenhouse gas emissions are in Mars’ supply chain and outside its control.

Most of those emissions come from farms.

“Almost 60 per cent of the company’s value chain GHG footprint (is) coming from agricultural ingredients,” says a Mars’ news release.

The company has concluded the best way to achieve a 50 per cent cut in emissions is by convincing thousands of farmers to adopt regenerative agriculture and follow climate smart practices.

“It does require the whole value chain,” said Emma Reynolds, global vice-president of corporate affairs for Mars Food & Nutrition.

“There’s no way we can do that without partnering with our farmers and supply chain.”

Mars was just one of many agriculture, food and ingredient companies that had vice-presidents and executives at the Reuters Transform Food & Agriculture conference, held Oct. 7-9 in Minneapolis.

Representatives of Cargill, Bunge, Bayer, Nutrien, McCain Foods and General Mills all spoke at the event.

Those firms have also set targets for cutting greenhouse gas emissions. For instance, General Mills has a goal of cutting 30 per cent from its GHG footprint by 2030.

The crux of the problem for these global companies is that sustainability goals are not hollow promises.

The reporting and accounting for sustainability within corporations is almost at the same level as financial reporting, representatives from a couple of firms told the Western Producer.

“We now have a sustainability controller. That was never something that would have been considered a couple of years ago,” said Robert Coviello, chief sustainability officer with Bunge.

Large corporations are now employing people who track emissions data and the progress toward sustainability targets because it’s become a reputational and financial risk that must be managed.

Chief executive officers worry that activist shareholders will accuse them of greenwashing (promoting false solutions to the climate crisis), which will prompt a story in the Wall Street Journal and a drop in their stock price.

There could also be regulatory risk as governments in Europe and Canada crack down on greenwashing.

Preventing negative press is one reason why food and ingredient companies are laser-focused on sustainability.

However, there are other drivers.

Buyers of oats, wheat, soybeans, coffee and other agricultural commodities want to improve the resilience of their supply chains. Food companies need ingredients every year, including growing seasons with drought, floods and extreme weather.

Another reason is that corporate leaders want to take action and make a difference around climate change.

So, General Mills, Mars, PepsiCo and many others in the food and agri-food industry have launched programs that encourage farmers to try regenerative ag practices, such as cover crops, reduced tillage and diverse crop rotations.

Kevin Burkum, CEO of U.S. Farmers and Ranchers in Action, which promotes agriculture as part of the solution to climate change, said there are 60 “lighthouse” programs that are building knowledge about regenerative and climate smart agriculture in America.

In Western Canada, General Mills has partnered with ALUS to advance regenerative ag on farms in Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

A group of growers, possibly 40 or 50, are receiving agronomic help and sharing data around best practices to improve soil health.

Public corporations, private companies and non-profits are going down the regenerative path, rather than promoting organic farming, because regenerative is something that can be done across millions of acres without a significant hit on crop yields.

In theory, if enough producers adopt regenerative practices, it could:

• Make food production more resilient to the extreme weather that’s associated with climate change.

• Cut emissions in the food and ingredients supply chain so that companies and countries can achieve their greenhouse gas targets.

• Accomplish these climate related goals without adding substantial costs to the agri-food system.

This all sounds great, but based on the conversations at the Reuters event in Minneapolis, no one really understands how to make this happen on tens of millions of acres.

The word “scale” was heard frequently at the Transform Food & Agriculture event with presentation titles such as “Scale Matters,” “Practical Insights on Scaling” and “Scaling Solutions and Partnerships.”

A representative of a major ingredients company admitted that convincing thousands of farmers to follow regenerative principles is messy and confusing.

“This whole (concept) could look much different in five years,” she said.

Plus, what farmers are required to do to become “regenerative” is poorly defined.

It’s difficult to measure the benefits of change if you don’t know what exactly is being changed.

One question that came up repeatedly at the Minneapolis event is, who will pay for all this as the industry transitions to regenerative agriculture?

Research done by Mars indicates that consumers do care about sustainability, especially younger people in the 18 to 34 age group.

However, when most consumers are at the grocery store, they think more about price, value, quality and taste than sustainability.

“A lot of consumers aren’t willing to pay more for a sustainable food,” said Reynolds from Mars Food & Nutrition.

The challenge for the food industry and its plan to promote regenerative agriculture is that change comes with a cost.

If farmers shift away from established practices, growing crops could become more expensive and less productive.

“Sometimes the practices we’re asking them to do, whether it’s cover crops or reducing nitrogen and other things, they’re not economically sustainable,” said Brett Bruggeman, chief operating officer of Land O’ Lakes, a farmer-owned co-operative.

“So, why would a farmer do that, unless someone is willing to pay (for it)?”

Florian Schattenmann, Cargill’s chief technology officer, said there is a general principle in production and in business.

When a new system or new approach is introduced, that system is not optimized and costs are likely to increase.

“We’re not in a super-high margin business. When you look at alternative pathways to do stuff … you have an un-optimized and new process,” he said. “And you compete with some sort of process that is fully optimized.”

Therefore, a shift toward regenerative agriculture will create new costs.

Asking a farmer to use less fertilizer or fewer pesticides may result in lower yields. As well, reducing emissions from agriculture will involve measuring, monitoring and reporting on nitrous oxide and methane emissions, which require people and salaries.

“The next level of sustainability will probably cost some more money,” Schattenmann said.

Some speakers in Minneapolis argued that regenerative ag practices and improved soil health will pay for itself.

That could be true 10 to 15 years down the road, but in the meantime, farmers need to make money, so someone or some funding needs to cover the transitional costs.

Corporations will step forward, but maybe non-governmental organizations and foundations need to offer incentives.

“Can you have a five-year window where (producers) get these subsidies that have a clear expiration date?” Schattenmann asked.

Nancy Kavazanjian, who farms in Wisconsin and is a United Soybean Board director, is taking advantage of the existing programs and financial incentives for regenerative.

She gets paid for no-till and seeding cover crops through a platform called Farmers for Soil Health, which connects producers with consumer packaged goods companies.

The additional income is useful in a year like 2024, with depressed prices for soybeans and other commodities, Kavazanjian said.

“I do feel I get paid very well for doing this.”

Tony Mellenthin, who also farms in Wisconsin, is more skeptical.

He worries about how his farm data will be used and how it will be shared. Plus, there are dozens of programs and incentives in America, which can be confusing for growers.

“It is an incredibly complex marketplace to navigate,” he said while on stage at the Transform Food & Agriculture event.

Getting the timing right could be a critical piece for food companies and the agri-food industry, which want this transition to happen.

Are farmers prepared to change how they grow crops in a time of weaker prices?

Maybe not, said Kasey Bamberger, who produces corn, soybeans and winter wheat on a 21,000 acre farm in southwestern Ohio.

Trying a cover crop for the first time and reducing nitrogen fertilizer is an interesting sales pitch, but it’s also a risk.

“Farmers will be hesitant to introduce new practices because they’re going to want to control the things they can control,” Bamberger said.

“You can’t risk losing money. There isn’t lot of money to be made in production agriculture right now.”

Contact robert.arnason@producer.com