Herbicide carryover should always be a concern following a dry year.

Throughout my career, I have seen this issue reoccur after every drought. This makes me think that 2018 could see herbicide carryover issues raise their ugly heads again.

In this column I will discuss why this issue is likely to show up and explain some of the practices you can consider to lessen its impact.

Herbicides are broken down in the soil generally by two mechanisms.

Many of them are broken down in soil by microbial decomposition. These include products belonging to the IMI class of herbicides, TPS (triazolopyrimidine) herbicides and some HPPD (inhibitors of p-hydroxyphenyl pyruvate dioxygenase) herbicides.

Read Also

Growing garlic by the thousands in Manitoba

Grower holds a planting party day every fall as a crowd gathers to help put 28,000 plants, and sometimes more, into theground

In addition, SUs (sulfonylureas) and triazines are broken down by chemical reactions such as acid hydrolysis.

Some herbicides, such as PPO (protoporphyrinogen oxidase) inhibitors, are broken down by both microbial action and hydrolysis.

Soil moisture or lack of it is important in understanding herbicide breakdown because both processes are highly dependent on adequate moisture to work.

Herbicide molecules must be free from binding to soil particles or organic matter for soil micro-organisms to degrade. Most herbicide molecules are more tightly adsorbed to soil particles in dry soils than moist soils. This shields them from breakdown.

In addition, degradation of herbicides in soil is affected by soil pH.

For example, acid hydrolysis nearly ceases at a soil pH higher than 6.8. IMIs, which rely on microbial activity and persist much longer in high pH soils, as does flucarbazone-sodium (Everest, Sierra). SUs persist longer under low soil pH.

The key time for herbicide breakdown is during the first 60 days following application. This usually coincides with rainfall and warm temperatures, which are perfect conditions for both microbial and chemical breakdown.

Temperatures decline as time carries on into the fall, which also reduces the speed of both breakdown mechanisms.

The amount of late fall moisture or snow during the winter will have little impact on the amount of herbicide breakdown one can expect the following year. The chart on page 69 illustrates a generalized breakdown scenario for dry and optimal conditions.

So what happens when moisture does arrive?

The herbicide that is sitting on the clay or organic matter gets flushed off into the soil water. At this point, it is still very much active and able to do what it was made to — kill plants.

Last year it was applied to a crop that had tolerance to it. This year it will not only kill weeds but also susceptible crops. It is now in the root zones of these plants and may act very much like the crop has been sprayed with this specific herbicide.

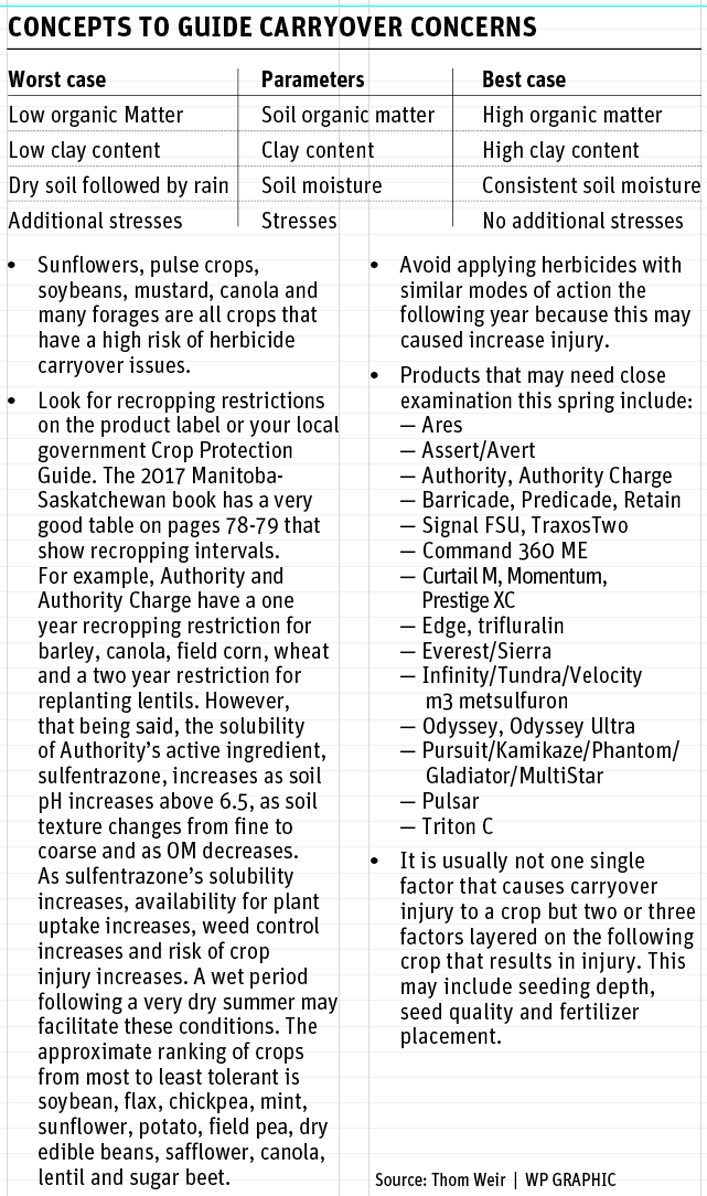

In my experience, the worst-case scenario for crop damage occurs in areas of a field with low organic matter (usually below four percent), where the soil pH is not conducive for that specific herbicide breakdown and when we get a drier period in the spring, followed by a rain.

These scenarios occurred in 1990 and 2003. Interestingly, it was newer herbicide chemistry that caused problems in both years.

In 1990, it was IMI (imidazolinone) chemistry, specifically Pursuit (imazethapyr), that caused the majority of the problems, and in 2003 it was Sundance (sulfosulfuron) and Everest (flucarbazone-sodium).

The reason, I feel, is that when new products are developed, the companies have to work with the data they are presented with: no drought and no data of carry-over under drought conditions.

As well, company marketing departments are jammed full of eternal optimists. Even when presented with “concerns” from research and development, they tend to look at the glass half full side of the argument and market “season long control.”

Now that you are in the final drafts for crop planning, it is a great time to review the herbicides that you used this past year and make a guesstimate of fields that may pose a risk for herbicide breakdown.

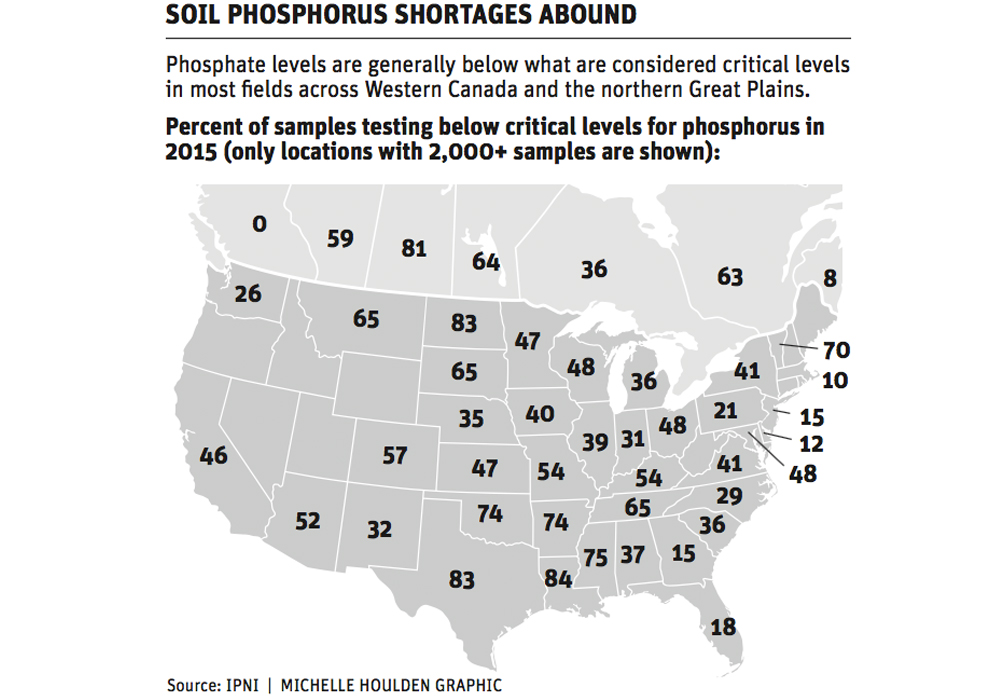

Saskatchewan Agriculture has created a great map that illustrates areas where last year’s lack of rainfall warrant concern. A prairie wide map from 2017 showing April 1 to Sept. 11 precipitation, both with this column, gives an idea of where the greatest risks are across the Prairies.

While not as accurate or useful as the Saskatchewan map, the precipitation map does give an idea where concerns might be warranted. Those who have on-farm weather stations can get very accurate information by querying rainfall from the date of your application until mid-September to provide very clear pictures of what was happening on their farms.

The next issue is what to do if you suspect you have crop injury because of herbicide carryover.

The first things to look for are areas of a field that are not emerging while the rest of the field looks normal. If these patches are observed, dig into these areas and try to find plants that have not emerged.

As well, look for other causes such as cutworms and look for plants that are growing on the patch margin that show symptoms of herbicide damage.

An excellent file of herbicide injury photos based on herbicide group can be found at bit.ly/2FAV8Pv.

Second observations should be made at about the time for herbicide application. Again, look for patches in the field that show either slow or abnormal growth. Look closely for symptoms.

Once you have observed what you think may be carryover injury, contact your herbicide supplier or manufacturer’s rep. Have them come out to look at your field.

Make sure you have information available for them to examine such as spray dates, rates, application maps, weather information and any soil tests you may have from the field.

With technology being what it is, it’s becoming difficult to find sprayer misses in a field. Look for misses or double application areas from your “as-applied” maps and examine those areas for patterns.

And finally, always remember that when going into a year like this, you should hope for the best but prepare for the worst.