No products are registered for control and ergot resistant wheat varieties are not on the horizon

Ergot is creating larger financial losses than ever on western Canadian farms.

Jim Menzies, a phytopathologist with Agriculture Canada, said the fungal disease, which infects rye, wheat and other cereal crops, has been showing up more frequently during the past 15 years in mainstream crops such as spring wheat and durum.

As the disease’s prominence grows, so does interest among the country’s plant pathologists.

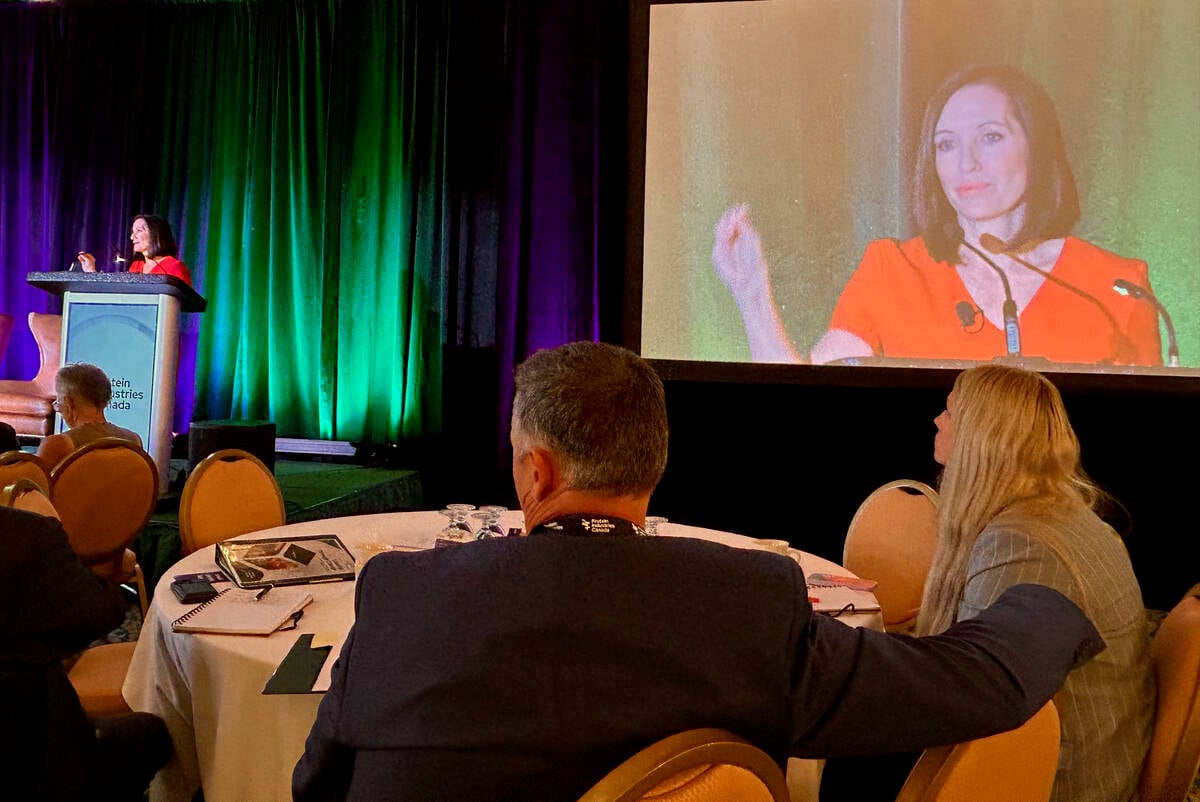

“Back in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, we did have ergot,” said Menzies, who spoke at recent Crops and Soils conference in Saskatoon.

Read Also

Canada told trade crisis solutions in its hands

Canadians and Canadian exporters need to accept that the old rules of trade are over, and open access to the U.S. market may also be over, says the chief financial correspondent for CTV News.

“You could find it but it was sporadic. Occasionally it would show up in a certain area, but then it would just go away. But since about 1999, it has become more regular and quite severe in some cases. Is it going to become a perennial issue? I don’t know. But it’s starting to look like it could be.”

Ergot research has traditionally ranked low on the list of priorities, primarily because the disease has been so sporadic.

But that could soon be changing.

Citing data collected from the Canadian Grain Commission’s harvest survey program, Menzies said the number of spring wheat samples that were delivered to elevators and downgraded because of ergot has risen steadily since 2003.

“In 2013, almost 50 percent of the wheat from Alberta was downgraded due to ergot,” he said.

“That was probably closer to 30 percent in Saskatchewan and 25 percent in Manitoba … so this is a disease that does seem to be a bigger problem in Alberta.

The number of downgraded samples was much lower last year, but that may have been because the grain commission relaxed the standards for ergot in the top grades of wheat.

All grade of spring wheat other than feed are now subject to a relaxed tolerance threshold of .04 percent.

Thresholds aside, it appears that the frequency of ergot infection is on the rise in Western Canada.

“When you look at 2013 and the number of samples downgraded, that also means that we have a very large increase in the amount of inoculum that are in the fields and ditches … which means we have a greater potential for ergot to reoccur,” he said.

Menzies said financial losses caused by ergot infection are primarily the result of downgrades at the elevator.

Yield loss is a consideration, but only a minor one, he added. Even in a heavily infected field, yield losses might amount to three or four percent.

“The real issue here is the presence of ergot bodies, and that’s because they contain toxic alkaloids,” he said.

“If you use ergoty grain to produce food, these toxic alkaloids get into the food supply and they can cause serious problems (in human health) and … with animals. It’s a human food and animal feed issue.”

Ergot infection is difficult to control.

The first visible signs of infection are the formation of small drops of honey dew, which appear on the immature heads of wheat and durum seven to 10 days after infection has occurred.

Dark coloured sclerotia bodies will begin to appear on the spikes by the end of July or early August.

By that time, spraying will do no good, Menzies said.

As well, no products are registered for control of ergot.

Menzies said there is no silver bullet for controlling ergot in grain.

Plant researchers have identified sources of genetic resistance, but the development of ergot-resistant wheat varieties is still “a ways down the road.”

The best defence against the disease is an integrated management strategy comprising quality seed use, proper crop nutrition, good crop rotations and other beneficial crop management practices.

Growers should begin with good seed, preferably certified stocks that have a reduced tolerance for ergot.

Cereals are susceptible to infection during flowering, so any steps that can be taken to reduce the flowering period will reduce the risk of infection.

Stressed crops are also more susceptible, which means supplementing micronutrient levels such as copper and boron might be beneficial.

However, the addition of copper and boron won’t eliminate the problem.

“I know there are some people out there who suggest that copper and boron will completely get rid of ergot, but I don’t believe that,” Menzies said.

Proper rotations are the trump card when it comes to prevention.

“There are a large number of diseases that will be controlled to a certain degree through the use of a proper rotation,” he said.

Contact brian.cross@producer.com