Farmland northeast of Winnipeg can produce great yields… if it doesn’t rain… but generally it rains.

“Drought” is a word that doesn’t exist in farmer’s vocabulary around here. “Flood” is a common word though.

The prevalent winds come sweeping down from the northwest, sucking up moisture from Lake Winnipegosis, Lake Manitoba and Lake Winnipeg. The clouds slow to drop their water on farming areas around Beausejour, Lac du Bonnet and East Selkirk.

Most growers expect to lose about 20 percent of their acres in a typical wet year, which can happen six years in a row. Farmers in the area joke that a perfect growing season is one in which they get no rain at all.

Read Also

Manitoba bans wild boar possession

Manitoba has tightened the regulatory status of Eurasian wild boar in an effort to help fight back against invasive wild pigs.

It’s an area ripe for a drainage return-on-investment study, according to Mitch Rezansoff, water management specialist with Enns Brothers John Deere in Oak Bluff, Man. He cautions that, like any major investment, it’s not wise to spend a lot of money on drainage machinery and software until you have a plan.

Rezansoff approached Joe and John Vanaert, who farm 4,300 acres at East Selkirk. They were frustrated with flooded fields and were ready to take action.

In 2014, Rezansoff was conducting research projects that touched on measuring inefficiencies, conducting on-farm research, managing variability, using big data and risk mitigation.

When it came to the topic of reducing risk through better water management the Vanaerts enthusiastically offered their farm for a case study.

In each of the previous three years, the Vanaerts had lost about 730 acres of cropland to excess surface water in spring, summer and fall.

The average loss of cropland in each of those three years was 17 percent, by far the most limiting factor on their farm.

Their plan was to start draining in 2014 on two fields totalling 353 acres, with the idea of having the entire farm drained by 2017.

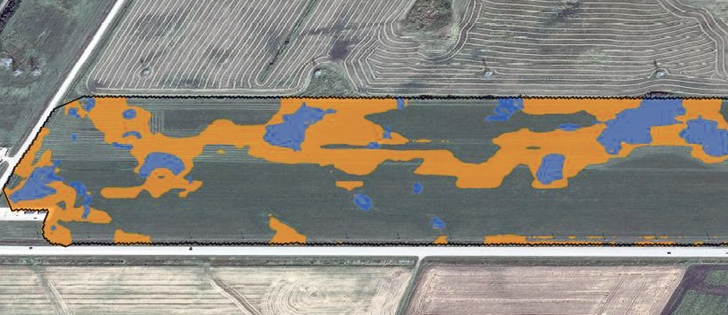

The 72 acre field had particularly well-defined low spots, simplifying the study process. Maps of the 72 acre field shows where water prevented crops from growing.

With input from Rezansoff, they bought a used scraper for about $50,000 and spent a similar amount on a John Deere RTK guidance system, giving them sub-inch accuracy on vertical and horizontal planes.

“As flat as their land is, one inch can mean the difference between water that flows and water that pools. If they expected to move water, it was essential to buy a high-end software package,” says Rezansoff.

For automation on the scraper, Vanaerts bought a John Deere software package called Surface Water Pro Plus. They also had to install new equipment on the tractor, including a flow rate controller for the hydraulics.

“It worked like this. John and Joe mapped the elevations on the two fields. We processed their data and provided them with a drainage plan. They wanted to move the least amount of soil in order to get the water moving in the right direction. They wanted the absolute most gradual slope to move water, because they didn’t want to have soil erosion.

“Then they went back into the fields with their tractor and scraper to confirm the drainage lines. That pass with the tractor records a guidance line. From that point on, he just presses the “go” button and the tractor steers itself. The scraper cut is totally automated. The blade goes up and down, up and down as the GPS co-ordinates guide the tractor along the prescribed drain line.

“When the scraper is full, the maps showed him the best depression areas where the dirt was needed.

Their whole goal was to move as little soil as possible and still have an effective drainage system. If you move the water off the field too quickly, it gets into the ditch, the ditches fill up and then water backs up onto the field again. Then you’ve accomplished nothing. The coloured flood maps show that their first drainage efforts had a significant impact.”

Rezansoff cites the example of the 72-acre field (see image above). The orange areas depict the 23.99 wheat acres Vanaerts lost to floods in 2014. The blue areas depict the 9.98 soybean acres the Vanaerts lost to flooding in 2015. Both coloured areas designate zero yield.

There had been no drainage in 2014, so the 23.99 flooded wheat acres caused a financial loss of $10,795. Some drainage was complete in the field before the 2015 soybean crop was planted, so the 9.98 flooded acres caused a smaller financial loss of $3,992.

In essence, they were able to farm 14 more acres on this field in 2015 than they farmed in 2014. It should be noted that soybeans are generally more water-tolerant. Rainfall was about the same in both years.

Drainage plans in the Selkirk area can be difficult to implement because so many long, skinny fields date back to the time of Lord Selkirk’s settlers, and they do not follow either the topography or the square mile section concept. The four-lane highway in the lower right corner is PTH 59.

“If he was just draining those 353 acres on the two fields we studied, he would have paid for his investment in five years. If he drained the whole farm with a good drainage plan, he might not have gained back the whole 17 percent of flooded cropland, but he might have gained 12 percent back, he would get his $100,000 payback in one year.”

Rezansoff points out that the cost of moving soil should be considered in any drainage plan. Field drainage in Manitoba dates back to the mid-1800s when horse-drawn scrapers gouged deep ditches. That mindset has persisted up to this decade.

People historically figured that a deeper ditch is a better ditch. That thinking resulted in fields that were a crazy puzzle board of scars on the landscape that modern big equipment can’t work through. He says growers are quickly catching on to the merits of wide, shallow drains with a gradual slope.

Rezansoff says the water route you select depends to some extent on the kind of soil you’re working with. He sees merit in the concept put forward by Jeff Penner, which advocates a drain route that meanders slowly around the field so water can percolate into the soil.

Taken to the extreme, the Penner concept would ensure that not a single drop of water would leave the field. It would all soak in so it’s available for crop growth.

“It makes perfect sense in areas where the subsoil allows water to move down, in areas where you have lighter or sandy soils. In the Red River Valley, water moves down only so deep and then stops. That white clay does not let water percolate down. Most of the guys we work with in the Valley are happy just to get the water off their fields.”