Wind projects expand | Manufacturers and maintenance workers in demand

Turbines are churning the winds of change in Canada.

The country is expected to generate 14,000 megawatts of electricity from wind by 2015 as it shifts from other energy sources.

Slightly more than two percent of Canada’s electrical needs are now supplied by wind.

Robert Hornung, president of the Canadian Wind Energy Association, said the country had slightly more than 300 mW of wind power generation in 2003, which grew to 5,000 mW by the end of 2011.

Contracts for another 5,000 mW have been signed, he added, and most provincial governments have adopted targets that, if all come to fruition, will generate 12,000 to 14,000 mW by 2015.

Read Also

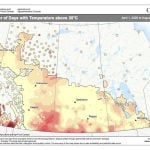

Factors that can cause heavy rainfall

There are several factors that can contribute to an extreme rainfall event, the first is atmospheric moisture.

“It’s driven by the need to invest in new generation within our electricity system as demand grows and as older generating stations start to come off line,” said Hornung.

Southern Alberta turbines generate about 850 mW, helping place Canada ninth in the world in terms of installed wind power capacity. The region has one of the best wind profiles worldwide in terms of frequency and strength.

Wind farm projects in various stages of planning and approval stand to double Alberta’s wind power capacity and are the reason for numerous electrical transmission lines proposed across the south. Several are controversial because they will affect farms and native grasslands.

“The (Alberta Electric System Operator) has actually been a strong proponent of building a transmission loop in southern Alberta that would allow 3,000 mW of wind to connect on the system,” said Hornung.

Though rates vary by location and company, payments of $15,000 per turbine per year can be paid to landowners.

Some companies play flat fees and others offer a percentage of income from electricity generated.

“There are certainly many, many farmers who appreciate the opportunity to have an additional alternative source of revenue on their land,” Hornung said.

The burgeoning industry is the wind beneath the wings of a supply chain designed to service it. Though there are no Canadian turbine manufacturing companies, there are operations that build towers, others that build blades and some that build nacelles and components.

“This has all happened essentially in the last four or five years,” said Hornung.

Manufacturing and turbine maintenance creates jobs, and thus the need for trained employees.

In the past, companies that erected turbines also looked after operation and maintenance. But now, as turbine numbers grow, companies are hiring firms specifically created to do those tasks.

Construction jobs are also created as wind farms are built.

Hornung said an Ontario study estimated an additional 5,500 mW of wind power would generate $16 billion in investment, create 80,000 person years of employment and add more than $1 billion to municipalities’ and landowners’ coffers over a 20 year project lifespan.

Canada doesn’t have wind projects that are more than 20 years old, but old turbines in other countries are often replaced with more modern ones, increasing capacity.

Kris Hodgson, wind energy liaison at Lethbridge College, said each three mW turbine costs $6.6 million, including materials, access roads, transport of parts, foundation and geotechnical services. They pay for themselves in about six years.

Turbines are criticized for killing bats and birds, but Hodgson said studies show fatalities can be reduced by up to 60 percent if turbines are shut down during the migratory season and at dusk and dawn.

Research continues, with the goal of further reducing bird and bat deaths.

Hornung also acknowledged criticisms about turbines.

“No form of electricity generation has no environmental impact. I think we can say quite confidently that when you compare wind to other sources of electricity generation, it’s clear that its environmental impacts are at the lower end. That’s not to say that people should not be cognizant of those impacts and be working to minimize those impacts going forward.”