HESSTON, Kansas – Southern Kansas in July has been described many ways, but “it’s hot like that other place, you know, way south of Heaven” came to mind recently as the mercury topped 35 C, the humidity chased after it and smoke from the burning of newly threshed winter wheat fields hung in the air.

Hot, dusty summer days in a town that doesn’t sell liquor and relies on agriculture for its livelihood might describe a number of small places on the U.S. Great Plains and Canadian Prairies.

Read Also

VIDEO: Green Lightning and Nytro Ag win sustainability innovation award

Nytro Ag Corp and Green Lightning recieved an innovation award at Ag in Motion 2025 for the Green Lightning Nitrogen Machine, which converts atmospheric nitrogen into a plant-usable form.

The stereotype would also include declining prospects and population, but that doesn’t describe this community of 3,500 just a 40 minute drive north of Wichita, Kansas.

The weather is hot in Hesston and so is business at the town’s largest employer, Agco.

A Fortune 500 company based in Georgia, Agco is best known for many of the products produced under the plant’s former name – Hesston Corp.

Hesston was Agco’s first acquisition after being formed from Deutz Allis in 1990. It was a short-line equipment company known for its forage machines, the first self-propelled swather and the first big square baler.

Begun in 1947 by Lyle Yost and a local machine shop owner, Adin Frank, the Hesston Unloading Auger solved a problem, as did many of the products that made the company a success.

Combines of the day had to stop in the field to unload, a time-consuming process made worse by a wartime shortage of farm equipment. For Yost, a custom combine operator, this was a problem he could fix, and the Hesston solution proved to be a hit with other farmers as well.

The company designed and built more than 70 combine accessories over the next decade. In 1955 Hesston commercialized the first self-propelled swather, followed by a variety of labour saving haying tools and balers. In 1978 the company released the world’s first big square baler, producing a four by four foot, 2,000 pound bale.

The workers needed to build the swathers and balers prompted Hesston’s Chamber of Commerce to credit the company with increasing the town’s population in the 1960s by 75 percent and then helping to increase it again between 1970 and 2000 by another 80 percent.

Despite struggles in the farm equipment market in the first part of this decade, the company is once again hiring.

Fiat bought into Hesston in the late 1970s and became the sole owner in 1987. In 1988 Case International purchased a 50 percent share and the plant became Hay and Forage Industries. In 1991 Agco acquired Fiat’s shares and the Hesston brand once again had American owners.

In the meantime, Hesston-made products were marketed around the world not only as Hesston but also as Case IH, New Holland and Fiat. Agco added the Massey Ferguson, New Idea and Fendt nameplates.

The company has also added other lines to its Kansas plant. Gleaner and Massey Ferguson combines and White row crop planters are built here and mowers, swathers and balers carry the names Hesston, Massey Ferguson and now Caterpillar Challenger.

The Hesston plant employs 1,700 people, most of whom live in and around the town. Until recently Yost could still be spotted in the hallway of the plant’s administration building.

Agco is undertaking a $13 million, three year reorganization of the six plant facility, not including the millions more spent retooling it with the latest in computerized and robotic cutting and welding equipment.

“It is being done without shutting down production,” said Kevin Bien of Agco.

“We can’t, there’s too much demand for the equipment.”

Andy Blandford, vice-president of manufacturing operations, said as a percentage of sales, Agco is spending more than any other large agricultural company in North America.

The company has moved from producing entire machines nearly from scratch to out-sourcing materials from other companies and Agco divisions, which it says makes better use of available workers and facilities in Hesston.

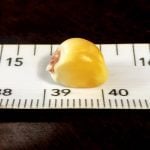

“There will always be some critical and complex pieces we will want to do here,” said Bien, citing baler knotters as an example.

Common platforms for machines of differing capacities and brands mean smaller inventories are needed, the assembly systems are streamlined and only the colour of the paint changes for individual brands.

The plant no longer builds an inventory of finished machines. Instead, each machine is built based on an order from a dealer, which is generally prompted by an order from a farmer.

Engineering director David Bisberger said the concept involves “mixed model production” rather than running a single product for several weeks and then switching to another.

The concept is supposed to reduce wait times for ordered machines, although company officials say a current worldwide machinery shortage means it might not seem that way.

The new production system simplifies work within the factory. There are fewer different parts, less local inventory, more space for production within the facility’s 34 roofed acres and increased work performed by machines and supervised by workers who are part of teams with designers and supervisors located on plant floors.

Complete sets of components for the machines are presorted and made available to assemblers as needed.

“Nobody needs to run from plant to plant trying to get bits and pieces any more,” Bien said.

As if to illustrate, 8.4 litre diesel engines from an Agco company, Sisu in Finland, sat inside Plant 5 July 15, waiting to be placed into transverse rotary Gleaner R combines and Massey Ferguson 9795 axial rotary combines. Different combines using the same engines sat back to front on the assembly line. Nearby shipping containers received what the company calls complete knock-down part kits for more simplified combine assembly at another Agco plant in Brazil.

The company is also expanding equipment testing at Hesston, what senior design engineer Tony Ward calls an aggressive testing regime for equipment designs.

To facilitate this, large stacks of tarped, round wheat bales sit at the back of the 350 acre plant facility, ready to be processed inside the bigger testing lab.

The Hesston plant forms about 20 percent of the town’s acreage.

Bien said while it might appear that the community relies on the company, it is really a mutual dependency.

“The facility grows and the town grows. If we can’t get staff, we can’t grow. The town and the surrounding area need us and we need them. A lot of local farmers work with us here, people who live in the surrounding area and some that commute from Wichita. But for the most part the folks who work at Agco Hesston are from Hesston. That’s the way it’s always been.”

The facility traditionally shuts down for two weeks in July to allow workers to avoid the heat and take summer holidays, but this year a few staff have volunteered for overtime to keep the facility running and equipment flowing to farmers.

Giant fans do their best to keep the air flowing past workers running welders, presses and brakes.

Only the robots fail to notice it’s July in Hesston, Kansas.