Hydrocracking technology may not be all it’s cracked up to be, says one of Canada’s leading biodiesel experts.

Some canola industry executives fear that hydrocracking, a catalytic process that breaks larger vegetable oil molecules into smaller ones, producing a diesel blend that is materially identical to regular diesel, will displace alcohol-based biodiesel plants.

Petroleum companies have expressed interest in the technology because it would allow them to avoid investing in expensive blending and transportation equipment required for regular biodiesel.

People like Judie Dyck, executive director of Saskatchewan Canola Growers, worry petroleum companies will use hyrdrocracking to fill the federal government’s proposed biofuel mandate, squeezing out farmer-owned biodiesel plants.

Read Also

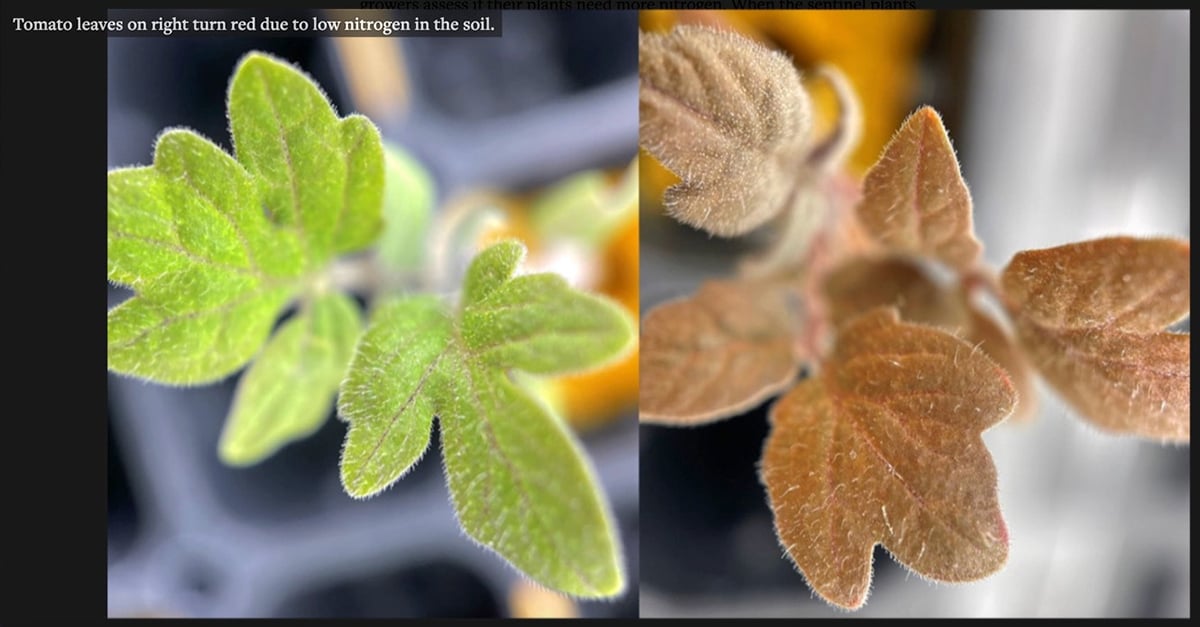

American researchers design a tomato plant that talks

Two students at Cornell University have devised a faster way to detect if garden plants and agricultural crops have a sufficient supply of nitrogen.

But according to Martin Reaney, a chemist with the University of Saskatchewan’s college of agriculture, hydrocracking has drawbacks that will prevent it from ousting conventional biodiesel production.

The process, which was developed and patented by scientists at the Saskatchewan Research Council, results in a net volume loss in fuel.

That is a money-losing proposition compared to alcohol-based biodiesel production because subsidies for the industry will be based on how much fuel is produced.

Hydrocracking is also criticized because it takes more hydrogen from natural gas sources to create it than regular biodiesel.

As well, glycerol, a byproduct of regular biodiesel production, is converted into propane through the hydrocracking process.

Propane is less valuable and it is hard to prove that it came from biological sources.

“How can you subsidize something like that,” Reaney said.

Lastly, the molecules that make biodiesel an effective engine lubricant are destroyed in the hydrocracking process.

“All the good things that I want to put in an engine to make it last longer, drive further, those are all wiped out,” said Reaney.

He thinks it doubtful that hydrocracking will turn out to be the preeminent biodiesel technology.

“I don’t think that they can compete head-to-head with a good (conventional) biodiesel manufacturing plant.”

However, Reaney believes there is a place for the technology for processing low-end oils like sewage sludge oil into biodiesel.