Porcine circovirus type two exists in every swine herd around the world, according to most veterinarians.

It exists in the Americas, Europe and New Zealand. It likely exists in Australia, although officials there are reluctant to diagnose it.

What to do about it is another matter.

Despite the presence of the virus, PCV2 doesn’t always manifest itself in disease.

The virus was first diagnosed as causing disease in a Saskatchewan barn in 1991. It surfaced almost simultaneously in Europe, but may not have been properly diagnosed.

Read Also

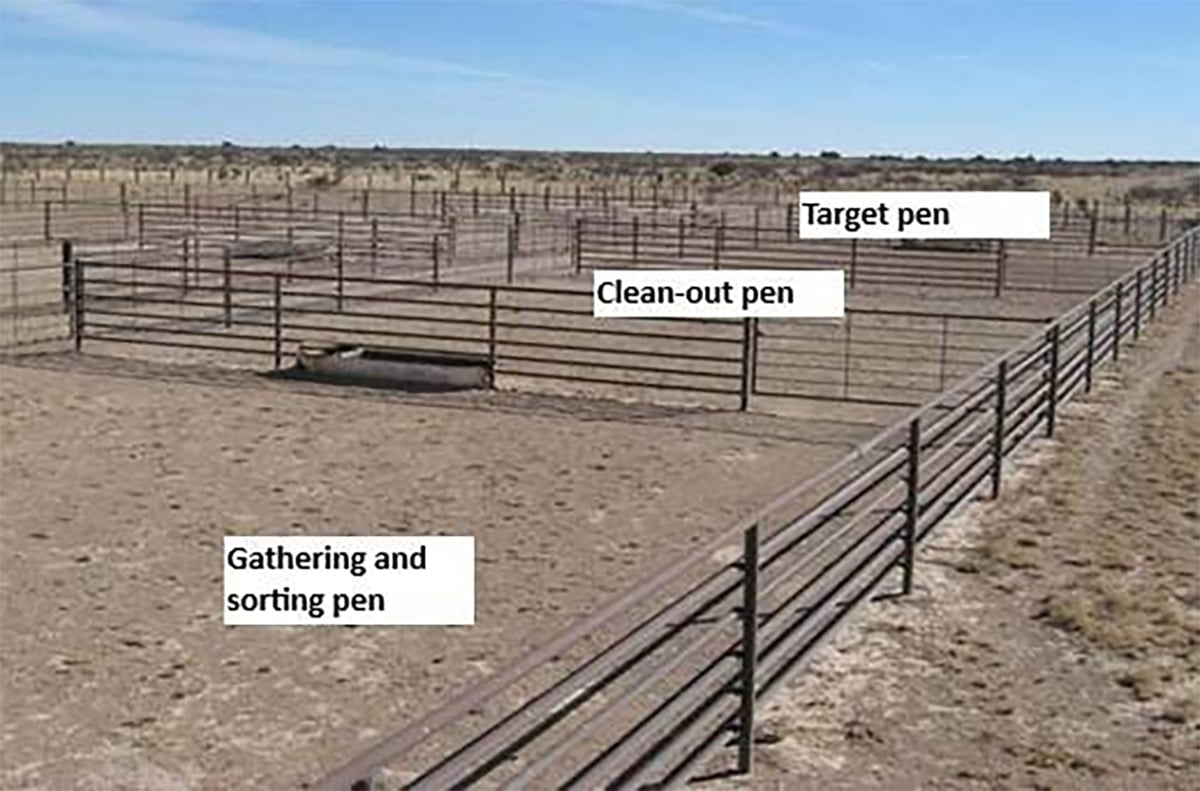

Teamwork and well-designed handling systems part of safely working cattle

When moving cattle, the safety of handlers, their team and their animals all boils down to three things: the cattle, the handling system and the behaviour of the team.

In fact, the virus was known to be present in Europe and elsewhere since the early 1970s but had not caused disease problems.

PCV2 shows up as other syndromes, mainly as acute pneumonia and post weaning multi-systemic wasting syndrome. It also appears as systemic infections, enteritis, abortions and porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome.

But these are not all of the diseases related to PCV2.

It’s part of proliferative necrotizing pneumonia in Quebec, Ontario and Alberta, PRRS in Ontario and Quebec and co-infections with strep-Glasser’s septicemia and Mycoplasma.

The disease is diagnosed by the appearance of razorbacks, potbellies, undersized animals or dime-sized skin lesions and swollen lymph nodes between the rear legs.

Diarrhea, acute pleuro-pneumonia and occasionally jaundice are also signs. It’s involved in the development of congenital tremors, shaker pigs, and heart thumpers, where the pigs’ hearts struggle to deal with pneumonic fluids in the lungs.

Statistically, PCV2 appears when mortality exceeds 50 percent of the national or regional level or when it is greater than the farm’s historical average mortality plus 1.66, multiplied by the mortality standard deviation, then squared.

Autopsies may show lungs that remain inflated after the chest is opened, enlarged, mottled kidneys and intestines lined with lesions.

Camrose veterinarian Frank Marshall told producers attending a Prairie Swine Centre event in Saskatoon at the end of March that in affected herds the average disease rate is 16.5 percent with highs to 40 percent and mortality of eight percent with highs of 41.

In a recent survey, 80 percent of

Ontario veterinarians said the disease was spreading.

In that province, it is estimated that of 5.2 million hogs marketed annually, 1.1 million or 22 percent are showing clinical signs of the disease. Nearly 90,000 animals will die of PCV2 related disease.

The cost of losses and treatment to Ontario farmers will be nearly $18 million this year. Quebec has similar problems.

Marshall said as mortality moves from an industry average of three percent to eight and finally 30 percent, margins per pig marketed decline from about $11.53 to $5.17 and finally a loss of $27.37. Mortality alone reduces margins by $1.44 per one percent of increased mortality.

“That adds up fast on a per sow basis,” he said.

In a market that is bringing $1.45 per kilogram, a one percent increase in mortality costs a producer nearly $35 per sow annually.

Western College of Veterinary Medicine researcher John Harding said new vaccines show promise in Europe, but so far aren’t available in Canada, so improving all herd health issues is the only way to reduce the problem.

“By reducing pathogen loads in the animals, the incidence of the disease can be controlled. The healthier your herd, the less likely you’ll have a problem with PCV2. And if you do have it showing up, the fewer losses you’ll have,” he said.