RED DEER – The most beneficial agronomic practices for malting barley production in southern Alberta are early seeding and appropriate rates of nitrogen fertilizer.

“My simple rule of thumb is, if you target what your yield potential is, what you probably need is around 1.2 pounds of nitrogen (per bushel per acre) – soil nitrogen plus fertilizer nitrogen – and that would be a reasonable target to go with nitrogen,” said Ross McKenzie, a fertility specialist with Alberta Agriculture in Lethbridge.

“If you start to go above that, in a wet year you’d be fine but in a dry year your protein would go up and kernel plumpness would decline.”

Read Also

VIDEO: Green Lightning and Nytro Ag win sustainability innovation award

Nytro Ag Corp and Green Lightning recieved an innovation award at Ag in Motion 2025 for the Green Lightning Nitrogen Machine, which converts atmospheric nitrogen into a plant-usable form.

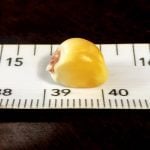

McKenzie told the annual agronomy update here that the maltsters don’t like peeled or broken kernels and they want at least 80 percent plump kernels, uniform germination, no frost or heat damage, no weathering or staining and no herbicide residue.

Before they accept barley for malting, two-row varieties require 80 percent or greater plumpness, less than three percent thin kernels and protein between 10 and 12.5 percent. Six-row cultivars must have 70 percent or greater plumpness, less than four percent thin kernels and protein between 10.5 and 13 percent.

McKenzie and other Alberta Agriculture researchers worked on malting barley from 1997-99, from the brown to the black soil zones. Researchers in Montana were doing similar work at the time, allowing McKenzie to compare Canadian and northern U.S. malting barley results.

“Farmers are most concerned about yield potential, but we’re also concerned about protein,” he said.

“Most of the sites we had, the protein didn’t go over 13.5 percent, so protein wasn’t that big a deal. For the drier sites, we did get over that level.

“The biggest factor when we looked at soil nitrogen and fertilizer nitrogen combined was the plumpness. The drier sites in Montana, they were below (80 percent) even before we got started putting on nitrogen fertilizer.”

More studies from 2001-03 looked at optimum agronomic practices for yield and quality in malting barley.

McKenzie said the sites were in the brown, dark brown and black soil zones across southern Alberta. The varieties included four two-row varieties of Harrington, Metcalfe, Kendall and Stratus and three six-row varieties Excel, B1602 and Sisler.

Each variety had 0, 36, 72, 108 and 154 lb. of nitrogen per acre applied. McKenzie included phosphorus, potassium and sulfur treatments. He tested seeding dates of late April, early May and mid-May, and seeding rates of 150-350 seeds per sq. metre.

“2001 was a very dry year, 2002 was a very wet year, almost excessively wet, and 2003 was near normal. We also had irrigated sites, as well,” he said.

“In 2001 under irrigation, barley yields were in the 150 bushels an acre range, but on dryland sites it was at 20-25 bu. an acre.”

McKenzie said within the two-row varieties, there wasn’t a huge yield difference. Protein levels were high in 2001, good in 2002, generally good in 2003 and were always low under irrigation in all the years.

“There’s very little difference between those varieties with regards to how they respond to nitrogen fertilizer. My bottom line is, if a farmer’s going to grow malt barley, you want to grow a variety the maltsters want, because from a yield potential standpoint, there’s not huge differences.”

McKenzie said weather had a greater impact on malting quality than agronomic practices in this study.

None of the practices provided acceptable malting quality under the extreme drought conditions of 2001. Under more typical conditions, agronomic practices did have significant effects on malting quality.

“Yield differences between the seven varieties were modest. Average grain yields were within three percent of the average yield of Harrington. Based on desired grain protein concentration and kernel size, acceptable malting quality was attained at 70 percent of sites for two-row types and 50 percent of sites for six-row types,” he said.

“Nitrogen fertilizer was the most influential agronomic variable affecting yield and quality in this study. Protein concentrations were within an acceptable malt range if nitrogen fertilizer was applied at rates just sufficient for maximum yield.”

In some cases, adding nitrogen caused a small reduction in kernel plumpness. This was especially noted at sites with good early season moisture and late season drought.

McKenzie attributes it to an increase in tiller and spike numbers during early growth, which increased the number of kernels beyond what could be properly filled.

Applications of phosphorus, potassium and sulfur did not affect malting barley’s yield or quality, but McKenzie said the lack of fertilizer response may have been due to the weather conditions over the three years of the study.

“I’m a big fan of phosphorus fertilizer and seed placing it. About 75 percent of the time, we see our best response to seed placing versus banding or side banding,” said McKenzie.

“With early seeding, we’re looking at lower soil temperatures, which means reduced availability of the phosphorus. Those cool soil temperatures translate into increased response to phosphate fertilizer.”

For potassium, only one out of 20 sites responded, so he’s not a big fan of that nutrient. McKenzie said he’s more concerned about sulfur on malting barley than potassium.

“If your soil test level is less than 10 lb. in the 0-12 inch depth, I’d be inclined to use a little bit of sulfur. Once you get up over 20 lb., you probably don’t need it.”

McKenzie used three seeding dates in his trials. The first seeding date was April 22, the second about 10 days later and the third 10 days after that.

“As we delayed seeding by about three weeks, we dropped the yield at every site. If we’re reducing our yield when we delay seeding malt barley, we’re concentrating more nitrogen in less yield, so the protein content goes up. If we seed a bit earlier, usually we get a little higher yield and it helps to keep the protein level down,” he said.

“When we increased our seeding rate on the first date, we got a little higher yield, but plumpness went from 90 percent down to 80 percent. For the second seeding date, we were at about 85 percent, but when we increased our seeding rate, we dropped down to 65 percent plumpness, which is not a good thing.”

McKenzie said delayed seeding reduced grain yield in all but one site in this study, consistent with other research results. The Alberta study showed a 20 percent yield loss from the earliest seeding date to the latest, about three weeks apart.

Research in Minnesota and central Alberta, with a five week spread between dates, showed a 35 percent and 47 percent yield drop, respectively.

Grain protein concentrations tended to be unaffected or slightly increased by delayed seeding dates.

On each date, barley was seeded at 150, 200, 250, 300 and 350 viable seeds per sq. metre. He said generally there was no yield response by going to an increased seeding rate.

The economic optimum rates in the study were about 200 plants per sq. metre on dryland and 250 plants per sq. metre under irrigation. For Harrington and Metcalfe, on brown and dark brown soil zones, that was about 85 lb. an acre. With black and thin black, at around 25 plants per sq. foot, that would be seeded around 119 lb. an acre.

MacKenzie said high seeding rates were more likely to reduce malting quality than increase it. Plump kernels declined about 10 percent under dry conditions and 2.5 percent in wet conditions.

High seeding rates were not effective in reducing the negative impact of late seeding.

“In 2001 we had a low response to nitrogen because of a lack of moisture. With no nitrogen, we were below 13.5 percent protein, but as we increased nitrogen fertilizer, our dry sites were as high as 17 percent protein,” he said.

“Our irrigation sites never did go over that 13.5 percent. In 2002, in a wet year, there was no problem staying below that protein level.”

McKenzie said the earlier a producer can seed, the better. It means more efficient water use, slightly higher yields, slightly lower protein and fewer problems with disease, weeds and insects.