It is that time of year when cow-calf producers sometimes need to deal with a very frustrating disease known as pinkeye.

The term pinkeye is really referring to any kind of inflammation of the conjunctiva of the eye. This is perhaps more of an “umbrella diagnosis” because there are numerous causes of conjunctivitis, including foreign bodies, viruses such as infectious bovine rhinotracheitis virus and a number of bacteria.

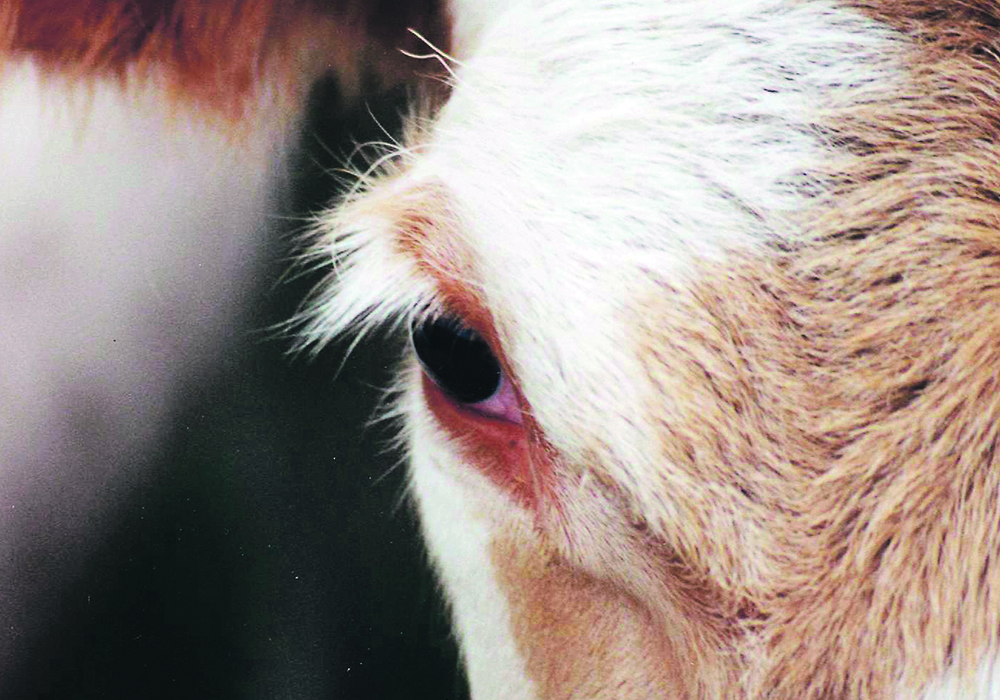

When most veterinarians and producers talk about pinkeye, they are referring to a condition of the eye that typically occurs on pasture and is characterized by ocular discharge, squinting or sensitivity to light, excessive tearing and inflammation (redness) of the cornea and the soft tissues around the eye.

Read Also

VIDEO: British company Antler Bio brings epigenetics to dairy farms

British company Antler Bio is bringing epigenetics to dairy farms using blood tests help tie how management is meeting the genetic potential of the animals.

It is more common in younger animals, and in approximately 75 per cent of cases only one eye is affected.

It is estimated that 2.8 per cent of the global domestic cattle population is affected by pinkeye every year.

This is a very painful condition, and as a result it can affect the animal’s appetite and cause some degree of weight loss.

In severe cases, the infection can lead to a corneal ulcer or an abscess within the cornea itself, and occasionally a corneal rupture and permanent blindness in the affected eye.

For the majority of pinkeye cases, a bacteria known as Moraxella bovis is the most likely cause.

This bacterium has pili or hair-like appendages that are found on their surface that allow the bacteria to attach to the cornea. The bacteria then releases toxins that cause the inflammation, resulting in the swelling and redness.

However, researchers have discovered other bacterial pathogens that have been described in association with outbreaks, including Mycoplasma bovis and Mycoplasma bovoculi. These bacterial organisms have been potentially implicated in outbreaks as well, but their role is still not fully understood and they can be found in many animals that are not suffering from pinkeye.

Carrier animals that harbour strains of these bacteria probably play a role in outbreaks, but more research is needed to identify how commonly this occurs and what factors affect shedding.

Several studies have shown that contributing risk factors to pinkeye outbreaks include smaller grazing areas resulting in a higher density of cattle, a predominance of younger animals and lower than average rainfall or dusty conditions.

Cases of pinkeye usually respond well to simple antimicrobial therapy if treated promptly, and a number of antibiotics are approved in Canada that have label claims for pinkeye, including the long-acting oxytetracyclines, florfenicol and tulathromycin.

The major challenge when dealing with this disease is identifying cases on pasture early, and then there is the obvious logistical challenges of treating animals while on pasture.

The disease can spread rapidly throughout the herd and often occurs in an outbreak situation, which makes treating cases even more challenging.

While we have excellent evidence that these antibiotics are effective treatments, we don’t have many good studies for some of the other potential treatments such as eye patches or ointments or sprays.

In most situations, we would really prefer to prevent an infectious disease from occurring in the first place. Unfortunately, we have few tools that can effectively prevent pinkeye and we can’t predict where and when the disease may be more prevalent.

Commercial vaccines are available for pinkeye, and some veterinarians have attempted to have autogenous vaccines made. However, the efficacy of these vaccines (both the autogenous and licensed products) has been evaluated in clinical trials, and the scientific consensus is that these vaccines are not effective in preventing pinkeye.

Several environmental factors have been traditionally associated with pinkeye. Could we address these factors to prevent the disease?

Ultraviolet radiation has been shown in experimental infections to be a factor that makes Moraxella bovis more likely to cause pinkeye.

As well, pinkeye outbreaks tend to occur in times of maximal solar ultraviolet radiation. However, providing shade is not easily done on many of our Prairie pastures, and how big an effect it would have on reducing pinkeye infections is unknown.

Irritation of the eye from grass awns has sometimes been considered a potential risk factor. This could result in foreign bodies in the eye and result in a condition that would mimic pinkeye.

However, there is no conclusive evidence that grazing tall grass is actually an initiating event for pinkeye, and good forage management would encourage longer grasses in our pasture.

Face flies are the most researched environmental risk factor.

It is important to differentiate face flies from horn flies. Most of the flies we see around cattle on pasture are horn flies. They are small and usually found on the backs, sides and poll area.

Face flies are similar to a slightly larger, darker house fly and tend to cluster around an animal’s eye, mouth and muzzle area. They can potentially cause corneal damage, which may allow infections to occur. There is also evidence that they can harbour Moraxella bovis and transmit it experimentally.

However, face flies have only been in North America since the early 1940s when they were accidentally introduced, and we know that pinkeye occurred before then.

A few studies have shown a weak correlation between the number of face flies and the prevalence of pinkeye, but the results are far from conclusive.

The bottom line is that the only environmental factor for pinkeye that we can attempt to control at all is face flies. There is some scientific evidence that fly control methods will reduce the number of pinkeye cases to some degree.

Talk to your veterinarian about the best antibiotic options for treating the disease.

John Campbell is a professor in the department of Large Animal Clinical Sciences at the University of Saskatchewan’s Western College of Veterinary Medicine.