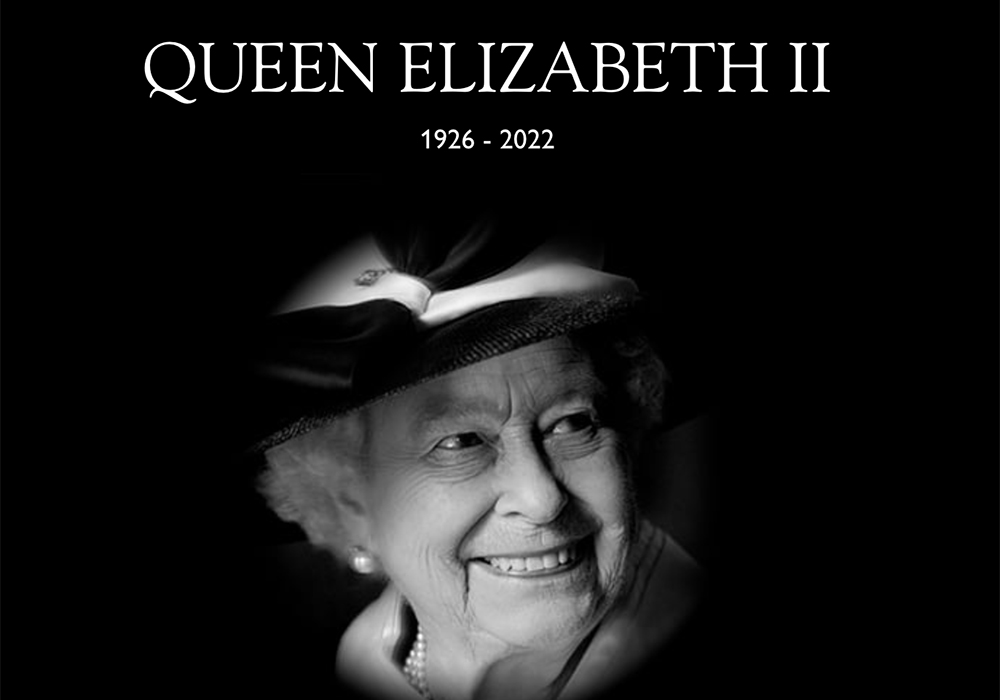

Seeing the centuries-old machinery of ritual whir into gear upon the death of Queen Elizabeth and the accession of King Charles is an awesome, perplexing, soothing or enraging sight, depending upon your outlook.

As a supporter of evolutionary development and stability, as well as a person who sees great riches in our heritage, I’m one of those who finds the present ritualistic passing of the crown from Elizabeth to Charles to be both an awesome and soothing sight. But I know many who look upon these ancient rites with perplexity, and some who have vented bile and outrage about them. These sorts of seismic events bring forth many feelings.

Read Also

Russian wheat exports start to pick up the pace

Russia has had a slow start for its 2025-26 wheat export program, but the pace is starting to pick up and that is a bearish factor for prices.

The Queen had many direct connections with western Canadian farmers, especially in the horse-breeding and riding communities, and I’m chatting with some about their experiences for an upcoming story.

The Queen bestowed the “Royal” title upon a number of agricultural bodies and events, such as the Royal Manitoba Winter Fair in 1970, and touched thousands in her many visits to Western Canada. Many in Saskatchewan take pride in her favourite horse, Burmese, being Saskatchewan-born and a product of RCMP training.

But the Queen’s greatest gift to the farmers of Canada is more in what she symbolized rather than anything she did directly. Her existence as a constitutional monarch, willing to keep her mouth shut about issues and to follow the dictates of our Parliament and those of her other realms, was a legacy of our orderly evolution as a society, in which revolutionary change has been avoided in the hopes of a peaceful advance and development that benefits all. We have had a willingness to allow things to be a bit messy, so long as they work.

Of course, many contradictions develop when differences aren’t flattened by revolution, civil war and authoritarianism, which are how most of the world’s nations have developed. Having a large, vibrant French society in the midst of an overwhelmingly English country is one. Being a federation is another, a challenge shared with our Australian and American cousins.

In agriculture we grapple with starkly different realities between Eastern and Western Canada, between swelling urban populations and a shrinking number of farm families, between the descendants of settlers and the descendants of the Indigenous people who signed the treaties.

We have agricultural policies that favour domestic dairy and poultry production for a protected domestic market side by side with policies designed for globally competitive and free-traded crops and meat. We try to encourage small farmers, while promoting the development of hyper-efficient large farms.

It can all look like a bit of a mess, a host of contradictions. But it works.

We often take this working-mess reality for granted, but we shouldn’t. Look at the messes that don’t work.

The world is rife with countries that continually cripple their own farming sectors, continually undermining successful commercial farming and making it an industry few want to invest in. It might seem vexing to farm in Canada, but it’s a lot more vexatious to farm in Zimbabwe, Argentina or dozens of other countries that should be agricultural leaders. Political instability can be a bigger factor in farming than rain, heat units, soil health and modern machinery.

Stability is often a bigger positive factor for businesses of all types, including farming, than anything else, so for all our messiness in policy, when we stitched “peace, order and good government” into our constitution, we embraced an approach that allows for a lot of messes, but works better than the alternatives.

In agriculture we’ve become world leaders in many industries, which is because of, not despite, our muddling-through approach.

As we watch the transition from the second Elizabethan age to the reign of Charles III we will be continually told that this constitutional and cultural structure is an anachronistic handicap upon our development.

But if results are what really counts, looking at the state of Canada and Canadian farming today, we seem to have hit upon something that works, despite its messy nature.

The crown may sit uneasily upon the head of Canada, but it fits.