If a year in farming didn’t have any surprises, it would be a strange year. From that perspective, 2016 certainly wasn’t strange. But it sure was a tough one.

While the low Canadian dollar was a dependable support for exporters, a roller-coaster of issues left many farmers stressed.

Some of it was uncertainty, for instance, with consolidation in the industry. Bayer agreed to a US$66 billion takeover of Monsanto. The new company would account for 65 percent of canola acres in Canada and 95 percent of canola trait businesses. ChemChina plans to take over Syngenta, which is a market leader in crop protection products and third in seed sales. And in fertilizer and the farm retail sector, Agrium and PotashCorp an-nounced a $36 billion merger. These deals have yet to clear approvals in many countries. A $130-billion merger between seed and chemical companies Dow AgroSciences and DuPont Pioneer is expected to close in the first quarter of 2017.

Read Also

Growth plates are instrumental in shaping a horse’s life

Young horse training plans and workloads must match their skeletal development. Failing to plan around growth plates can create lifelong physical problems.

The row continues over Alberta’s farm safety act, which was passed last December. In October, one of six working groups analyzing the details disagreed on whether unionized farm workers should be allowed to strike.

Country-of-origin labelling legislation was repealed by the U.S. Congress last December, but will it be back under a Donald Trump presidency?

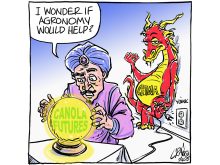

And as time ran out in September, China agreed to maintain dockage rules until 2020, permitting Canada’s $2 billion in canola exports to continue.

In November, Health Canada said it wants a three-year phase-out of imidacloprid and it will investigate two other neonicotinoids because water bodies near agricultural lands have high concentrations of the insecticide. Farm groups offered a mixed reaction.

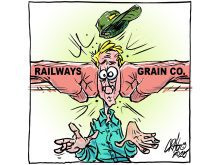

Then came the harvest from hell. What looked like a bumper crop was pummeled by mid-summer rains that were so heavy one farmer took to water-skis in a canola field. The watery conditions persisted, delaying the harvest. By late October, it was estimated that the value of unharvested grain and oilseeds was about $2 billion in Saskatchewan and $1.6 billion in Alberta. Expectations of record lentil and pea production were tempered by the late harvest and wet conditions, which damaged the quality. An extraordinary November allowed many farmers to finish harvest.

The problems — fusarium in wheat and barley, lower quality crops across the grain and oilseed spectrum — likely won’t be offset by what still turned out to be a huge harvest.

Livestock farmers fared no better. Prices that had nearly doubled over four years dropped by almost 40 percent by September. Then, Western Feedlots announced it would close its cattle feeding operations in Alberta, removing capacity for 80,000 to 100,000 head.

And then came bovine tuberculosis. One cow was discovered with the contagious disease in September. By late December, 34 ranches in Alberta and two in Saskatchewan were quarantined, affecting 26,000 animals. Up to 10,000 may be slaughtered. About $16.7 million in assistance has been committed to Alberta ranchers through the AgriRecovery program.

The year ends with intense debate over Ottawa’s proposed carbon tax, which, by one estimate, could cost farmers with 2,000 to 2,500 acres about $10,000.

It’s understandable that many farmers will be glad to see the backside of 2016, but there’s little doubt 2017 will bring more surprises, some good, some not so much.