Is it a fantasy for farmers to think they will be able to get premium prices from the market for embracing enhanced animal wellness in facilities and practices?

I suspect so, and I’ll lay out here why I think the way I do. (Please post comments telling me why I’m an idiot if you think I’m wrong. I’m just thinking through what I think is most likely as these issues evolve. None of the following is what I necessarily think should, happen, but just what I suspect is most likely to happen.)

Read Also

Farmer ownership cannot be seen as a guarantee for success

It’s a powerful movement when people band together to form co-ops and credit unions, but member ownership is no guarantee of success.

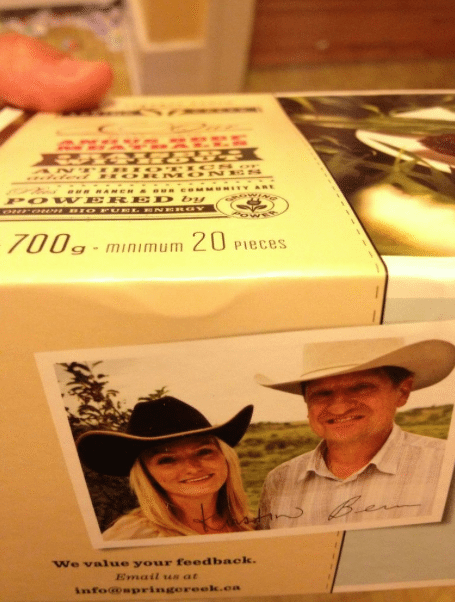

First, a preamble: Farmers can definitely squeeze premiums from small parts of the consumer market for perceived value-added elements to their product, such as being organic, fair trade, grass-fed or produced by nice farmers and ranchers identified on the packaging. Just the other day I bought a package of meatballs from Safeway produced by Spring Creek Ranch, and I bought it because it seemed nicer than the generic meat balls beside it in the freezer. I paid a couple of bucks extra for it. I liked the idea that a wholesome farm couple in Alberta was going to provide the supper I was about to give my kids.

And providers of free range eggs have been able to charge high prices for those spheroids for years. And specialty food stores and farmers markets can have high prices.

So it’s not like premiums don’t exist for some specialty products at some times in some places. A good present case will likely be A + W’s decision to be fussy about the beef it buys from Canadian farmers. That will probably allow some farmers to charge the burger chain or its packer more for their cattle than they’d be able to get selling it as simple commodity slaughter at the packing plant.

But I don’t think premiums are as likely to appear for either pork from open-housed sows or from eggs produced from chickens raised in “furnished” or “enriched” cages, or at least not for long and not consistently.

Some hog farmers I’ve spoken to about the gestation stall issue in recent months have said they think farmers who switch to open housing for gestating sows should be able to get premium prices for their pigs to reflect the growing consumer demand for open-housed sows. If the consumer wants it, they should pay for it, I’ve been told. They think premiums should appear, farmers who provide the housing will be rewarded, then more farmers will convert their barns to open housing to get the higher prices, and a virtuous cycle will transform the industry. I’ve heard the same thinking from some egg producers over the last few years, as they also face a consuming public and food system that wants product from more humane-seeming systems.

It’s a nice idea, with price incentives leading farmers to voluntarily convert from one system to another with no coercion involved.

But I’m guessing that what is more likely to happen is that:

1) More food providers will demand open-housed animal products;

2) Some farmers, and almost all those building new facilities, will move to open housing systems because they aren’t willing to take the risk that they’ll build facilities that are banned in future legislation or can’t sell their livestock to packers in the future;

3) At a certain point, when enough supply exists, some major packers and processors will start running lines of open-housed-only meat, but they won’t do it until there’s enough supply to stop farmers squeezing them for higher prices;

3) Those packers will be able to get a marketing edge over their competitors with a few grocery chains, and the packers might be able to squeeze a premium from the grocers, but farmers won’t have the leverage to do the same;

4) The other packers will say “Holy Crap, we’re losing sales here!” and they’ll rush to also offer open-housed products as their general, generic product. But as they get ready to source and provide open-housed meat, they’ll compete by trying to slash prices and undercut the open-housed products;

5) Farmers who aren’t able to offer open-housed product will find fewer and fewer buyers for their livestock, and those who do buy will be able to do so at a sharp discount because not only is the meat harder to move, but they’ll know they have those farmers over a marketing barrel;

6) Everyone who wants to stay in the business decides at that point that they’d better convert now, or get out of the business.

To me the difference between the open housing issue and things like organic, fair trade and farmer-identified foods is that there’s a gun pointing at the back of the head of the farmers producing livestock and animal products in non-open systems, but there isn’t for the other issues. No one significant is going to legislate that all coffee be sourced from fair trade networks. But at some point, governments could just legislate an end to gestation stalls and battery cages, as happened in Europe. Or grocers could just refuse to carry products from conventional systems. (The latter is the scenario I played with above.) Either way, farmers don’t seem to have much leverage on the issue, and leverage is the only thing that allows someone to demand a premium in the marketplace.

So what do you think? How is this issue likely to evolve in the coming years? I’ve given you my guess. What’s yours?