Farmland prices climbing | Financial experts predict prices will plateau as interest rates start to rise

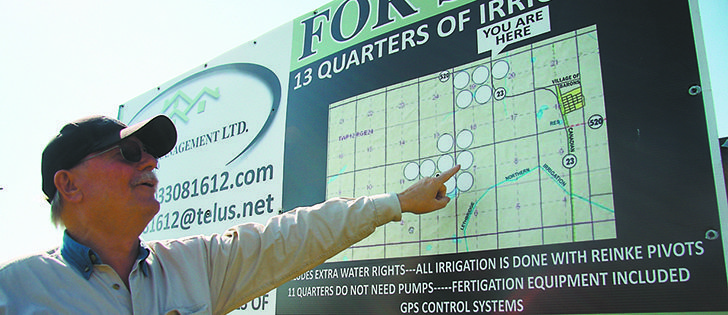

BARONS, Alta. — The price tag was $9 million when Barry Allen’s 13 quarter sections of farmland were first listed six years ago.

Now the price is $13 million, and realtor Brian Patterson says it’s a gift at that.

The big number is posted on a billboard along southern Alberta’s Highway 23, where it attracts a lot of attention. However, Allen said it hasn’t resulted in anyone visiting his farm with a cheque in hand.

The rising price of the farmer’s irrigated cropland near Barons is typical of farmland price booms across most of the country. The cost of agricultural land rose 10 percent during the second half of 2012 alone, according to figures compiled by Farm Credit Canada.

Read Also

Taking a look inside Canada’s seed regulatory overhaul

ive years, eight task teams, 130 volunteers and 135 recommendations later, Canada’s seed industry is still waiting for meaningful regulatory change.

In this part of fertile southern Alberta, quarter sections are selling for upwards of $1.6 million, even when they aren’t listed with realtors.

“(Farmland) doesn’t go on the market,” said Patterson, an associate broker with Clear View Property Management.

“It’s sold way before it goes on the market. People, as soon as they hear that somebody is thinking of selling a piece of land, it’s bought. It doesn’t go on the market that often.”

FCC reports that farmland values are stable or rising in all provinces. Bob Lane of Regina-based Lane Realty said land prices in Saskatchewan are lower than those in other provinces but remain on an upward trend. Sales are also brisk.

“It’s moving faster than it has in the past,” he said.

“When we do bring a property on stream, it seems that it would be moving quicker than it has at any other time in my 38 years in the business. I think the market is stronger than it was in 1981, which was our last sort of peak in the market before high interest hit us in 1982.”

Lane said there’s more activity in Saskatchewan farmland sales than ever before, but prices are lower than in other provinces because of several factors.

“We have twice as much land available as Alberta does, and three times Manitoba, and we only have a million people here and Alberta has over three. We only have 57 Hutterite colonies and Alberta has 230, I think, and Manitoba has 112.”

Prices for farmland vary so widely that Lane declined to provide a ballpark figure per acre or per quarter. However, he said prices are up about 11 percent over last year.

Don Close, vice-president of food and agribusiness for Rabobank, said he thinks land prices, though driven recently by favourable commodity prices, might soon reach a plateau.

“Rabo is of the perspective that, while we have not yet seen an absolute peak in land values in the U.S., we think that they have certainly started to flatten out and that we’ll very likely have some kind of correction down the road,” he said.

Once commodity prices lose their heat, land values will be driven by interest rates and financing, he told a recent meeting of the Alberta Cattle Feeders Association.

In the United States, land values hovered around $1,000 to $1,500 per acre, on average, when interest rates were at six percent or more. Land prices then escalated with support from grain prices, and interest rates dropped.

“As we’ve gone into this extended period of sub-three percent interest rates is when we’ve seen the big run-up in land values, in the $8,000 to $12,000 bracket.”

Close said Rabobank predicts interest rates have reached their nadir and will rise by late this year or early 2014.

“It’s our perspective that interest rates have seen their lowest level, and as interest rates start to escalate, that will be the biggest driver on seeing some stabilization or even a correction in land values going forward,” he said.

However, Patterson thinks the worldwide shrinkage of available irrigated land, much of it in areas dependent on aquifers, will keep prices high for irrigated land like that owned by Allen.

He’s had inquiries about the Barons property from China, India and Holland, where such large tracts are unavailable and where irrigation opportunities are growing ever more limited.

Allen’s property has the advantage of irrigation water rights obtained in return for allowing a major expansion of the Lethbridge Northern Irrigation District on land owned by him and a neighbour.

“One of the really, really big features of this land is the fact that the irrigation district supplies the pressure, which eliminates the need for a pump. And anybody that’s ever irrigated will realize what an advantage that is.”

As a result, Allen said the land “will grow any damn thing you want,” and in fact has had crops of wheat, canola, barley, alfalfa and potatoes in the recent past.

The retired farmer, now 69, rents the land to the White Lake Hutterite Colony, which has first right of refusal should a purchase offer be made. His children have other careers so there are no family members interested in taking it on.

“It would be nice to pass it on to the family,” said Allen. “My great-grandfather came here in 1903.”

Allen owns five quarters and his uncle owns the other eight. Selling it as a package is important to him, even though Allen said he could sell his five quarters tomorrow if he wanted to.

He doesn’t want to.

“The neighbours and families are interested, but they haven’t knocked on the door yet. That would be wonderful, but it hasn’t happened. Life goes on, but what happens when I die? They’ll sell it to anybody.”

Patterson said he and Allen have witnessed situations where farmers die without passing on the farm, and viable operations are then sold piece by piece at less than their true value.

“When Grandpa passes on and there’s nobody else to continue with the farm, I’ve seen it so often that they’ve been taken advantage of, by the adjacent people, by professionals, such that they get nowhere near the market value for the land or for the products or for the stuff that’s left on the farm,” Patterson said.

Hence the billboard in the field, with it’s big number.

“I don’t see a down side to it,” said Allen about the in-field advertisement.

“My feeling was that it kind of eliminates a lot of tire kickers. Don’t phone for a quarter (section). The price is $13 mil.”