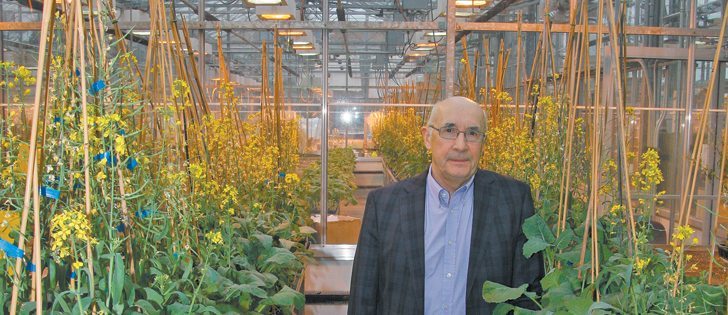

Wilf Keller helped transform genetically modified canola from a green speck in a petri dish into the biggest moneymaker in Canadian agriculture.

A technology that is now incorporated into 21 million acres of canola got its start in 1985 in the obscure Agriculture Canada lab he ran in Ottawa.

Canola generated $7.3 billion in farm cash receipts in 2011, which is more than any other crop or livestock category.

According to the Canola Council of Canada, almost all of Canada’s canola acres are seeded to genetically modified varieties that have evolved from that green speck in Keller’s petri dish.

Read Also

Pakistan reopens its doors to Canadian canola

Pakistan reopens its doors to Canadian canola after a three-year hiatus.

Keller grew up on a mixed farm near Melville, Sask., and graduated from the University of Saskatchewan in 1972 with a doctoral degree in crop science.

He did postdoctoral work in Germany and was then hired as a research scientist by Agriculture Canada, where he set up a new area of research using cell and in vitro tissue culture methods.

“When I got hired there, the term biotechnology didn’t really exist yet,” said Keller.

His first long-term project laid the groundwork for the discovery of herbicide tolerant canola.

Keller was culturing pollen from male canola plants and tricking the microspores into growing into a plant without mating with a female cell.

“It would be like getting an animal out of a sperm cell,” he said.

“ You have only the paternal set of genetic information and you can select much more easily for desired traits.”

Senior management at Agriculture Canada recognized the potential of Keller’s work and appointed him to head a team of four scientists that would pioneer double haploid breeding technology for brassica species, which seed technology companies still use.

The technology allowed breeders to cut out several generations of field work, vastly reducing the time needed to commercialize varieties.

“Instead of 10 years, you might get a variety in seven,” said Keller.

Kutty Kartha, former director general of the National Research Council’s Plant Biotechnology Institute, said double haploid technology is an exceptional breeding tool.

“That is one of Wilf’s major contributions and he got very good recognition for that,” he said.

It was also the foundation for the creation of the world’s first GM canola plant.

Keller’s research attracted the attention of Maurice Delage, a former college buddy who was president of Hoechst AG, a German chemical company that through various mergers and acquisitions became AgrEvo, Aventis and then Bayer CropScience.

Delage visited Keller’s Ottawa lab in 1985, “snooping around” for a program that could help his company develop the world’s first herbicide tolerant canola.

Hoechst had a gene it had isolated from a bacterium that conferred resistance to the chemical that would become Liberty.

Keller showed Delage the thousands of embryos he had in petri dishes, which was part of his double haploid work.

The company immediately dispatched one of its young German scientists to work with Keller in Ottawa. The two researchers used a blender to macerate the tissue derived from the canola microspores and create a plant material sludge.

The sludge was infected with the bacterium that carried the gene for herbicide tolerance. It was then treated with the herbicide, which killed everything except cells that had adopted the beneficial gene.

“There was one green spot in one petri plate and we regenerated that plant,” said Keller. “We got this plant and it was sprayed and it was resistant in the greenhouse.”

Keller joined the NRC’s Plant Biotechnology Institute in 1989 as group leader for canola biotechnology research. Hoechst followed him to Saskatoon, where they completed the development work on GM canola.

Innovator canola was field tested in 1991 and commercialized with a small group of farmers in 1995. Widespread adoption of the technology had occurred by 1997, prompting concerns from the public and the media.

Keller became the go-to-guy for fielding media calls, even though he wasn’t part of commercializing Innovator canola.

His first big interview in 1997 with CBC TV’s The National didn’t go well, and Keller decided he had better get media training.

Keller then toured the country to educate people about the science of biotechnology by condensing years of research into bite-sized bits of information.

“It was a whole other world, knowing how to answer something in 30 seconds or a minute at most and explain it in a way where you’re not using jargon,” said Keller.

Kartha said Keller’s interpersonal and communication skills were two of his biggest strengths aside from his research ability.

“Most scientists, although they can communicate, they use jargon and they get lost, whereas Wilf communicates in simple terms so ordinary people on the street can understand what he’s talking about.”

Kartha said Keller got to the point where he enjoyed debating people about the technology.

Keller’s contributions to the canola industry didn’t stop with GM canola.

In his role as research director and eventually acting director general of PBI, he oversaw a genomics program that shed light on the development of canola seeds.

He believes genomics will be a more powerful breeding tool than double haploid technology and lead to a multitude of new useful crop traits for farmers.

“This will be transformational. I think it will allow for the development of varieties down the road that will have highly desirable, superior features.”

He anticipates that genomic-based plant breeding will be commonplace by as early as 2025 because the cost of sequencing a genome is rapidly declining.

Keller was courted by the private sector but remained in the public research stream for his entire career.

“He liked to work for the federal government, the public sector. There was more freedom and excellent laboratory facilities,” said Kartha.

Keller cherished the ability to conduct foundational research early in his career.

“There was a rich environment in Agriculture Canada in those days to do this kind of work, where you would explore a biological process that might not have immediate relevance,” he said.

He doesn’t believe he could have been part of the same research advancements in today’s world, which is focused on short-term research projects that can be quickly commercialized.

“Maybe I wouldn’t have had the timelines that were given to me in 1970 to go ahead and work for five years before somebody asked too many questions, which is basically what happened.”

Keller retired from PBI in 2008 and became president of Genome Prairie. He is now serving as president of Ag-West Bio, a non-profit group helping to advance Saskatchewan’s bioscience industry.

However, he misses the excitement of research discovery, such as playing a key role in transforming a green speck in a petri dish into a multibillion-dollar crop.

“I had the privilege of watching (that unfold) from that first plant in a small obscure laboratory in Ottawa,” said Keller.