Dos and don’ts when sampling wild oats for testing:

UPDATED: September 29, 2020 – Please note: The Prairie Herbicide Resistance Research Lab tests only weed biotypes that remain unconfirmed regarding herbicide resistance. It does not offer routine testing of weed samples, which are best done at various diagnostic labs on the Prairies.

Farmers who suspect herbicide-resistant weeds in their fields can have samples tested, and those samples are best collected before harvest.

Charles Geddes, Agriculture Canada research scientist who studies herbicide resistance, said wild oat seeds should be collected before harvest because most available tests involve growing the seeds and then subjecting them to herbicide treatments to determine resistance.

Read Also

Growing garlic by the thousands in Manitoba

Grower holds a planting party day every fall as a crowd gathers to help put 28,000 plants, and sometimes more, into theground

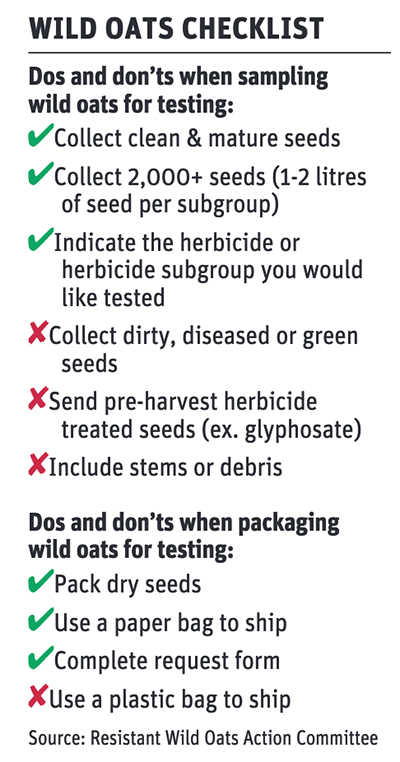

Ideally, farmers should collect clean, mature seed with about 2,000 seeds per sample, Geddes told participants in a webinar organized by the Alberta wheat and barley commissions. Samples should be collected before any pre-harvest herbicide treatment is applied

If wild oats are the target, 2,000 seeds will be one to two litres. Geddes recommended using an insect sweep net to collect the sample. Sweeps will dislodge the desired mature seeds.

The sample should be free of green seed and dry so it doesn’t mould during shipping. Seeds should be packaged in paper bags or other breathable material, rather than plastic.

Russian thistle and kochia samples can be collected after harvest, said Geddes. Sometime in October is likely best.

Geddes said the problem of herbicide-resistant weeds continues to grow.

There are 76 unique biotypes in Canada. In prairie weed surveys conducted in about 800 fields from 2014-17, 68 percent of Manitoba fields surveyed had herbicide-resistant weeds. In Alberta, 59 percent of surveyed fields had them and in Saskatchewan the figure was 57 percent.

There are a limited number of herbicide modes of action and the last new one was released in the late 1980s. Developments since then have primarily focused on reformulations of older modes, Geddes said.

“Almost 24 million acres of the Prairies are infested with herbicide resistant weeds and this costs prairie growers about $528 million annually, which is a large sum of money. And these metrics are actually based on farmer reported costs of resistance.”

Specific to Alberta, Geddes said about 58 percent of fields have wild oats resistant to Group 1 herbicides and 40 percent of surveyed fields are resistant to Group 2. Almost 30 percent of fields have wild oats resistant to both.

Some are also resistant to Group 8, said Geddes, and more data on that is expected to be available soon.

As a result, “we have very few post-emergent options” to control wild oats in cereals, though some remain for canola.

“This shows how important it is to maintain canola in a crop rotation to help with managing herbicide-resistant wild oat. The other important thing is that all of the remaining pre-emergent herbicides… are labelled for suppression only, so it means that essentially we have pre-emergence herbicide options but they’re labelled only for suppression and we don’t have post-emergence options in this case,” Geddes said.

As for kochia, Group 2 resistance was found in the late 1980s and now all kochia in Western Canada is resistant. Glyphosate resistance was found in 2011 and by 2017 about 50 percent of surveyed fields had resistant kochia. Dicamba-resistant kochia was also found in 2017. Alberta fields will be surveyed for kochia again in 2021, Geddes said, and he anticipates an increase in levels of resistance.

The wily weed has a prolonged emergence period and even if emerging in August, it can produce viable seed before killing frost.

“That’s a large issue when managing kochia,” said Geddes. Non-chemical tools are part of the answer in dealing with it. A competitive crop, for example, can reduce the seed load in a subsequent year.