Risks to cattle increase as sulfate concentrations in water rises.

A quality water supply is a key component of pasture health where cows and calves are expected to thrive during the grazing season.

Water intake affects feed intake, nutrient absorption, weight gain, milk production, fertility and temperature regulation in cattle, and cows need nine to 21 gallons of good water per day, depending on lactation and temperature, to meet all those goals.

Leah Clark, livestock specialist with Saskatchewan Agriculture, advises cattle producers to have pasture water sources tested so animals will not limit their intake, thereby also limiting their production.

Read Also

Beef check-off collection system aligns across the country

A single and aligned check-off collection system based on where producers live makes the system equal said Chad Ross, Saskatchewan Cattle Association chair.

“Water is the most important essential nutrient. I’ve often times referred to it as the forgotten nutrient,” said Clark.

“Limiting water availability to cattle will depress production rapidly and severely so poor quality drinking water is often a factor in limiting intake. Often times, I don’t think we necessarily address this.”

Clark and Brenna Grant, manager of Canfax Research Services, recently collaborated on a water quality webinar organized by the Beef Cattle Research Council.

When it comes to testing water, hand-held testers are available but Clark said their results should be viewed with caution. Though some meters claim to measure total dissolved solids (TDS) in water, they actually test conductivity and then use a conversion factor to provide a result.

Clark and her colleagues compared hand-held meter results with those from laboratory analysis and found the hand-held data varied considerably from professional tests. Though meters can be good screening tools that can alert to potential water problems, lab tests remain the gold standard, Clark said.

Maximum TDS in water for cows and calves is 4,000 to 5,000 milligrams per litre. Levels above that will likely affect productivity.

Clark warned producers specifically about sulfate levels in water. Studies are underway to learn more about tolerable levels. Dry prairie conditions tend to raise sulfate levels in surface water.

In 2017, a dry year, Clark said almost half the 600 water samples she and her colleagues collected had levels unsuitable for livestock consumption.

She said there were fewer similar issues in 2018, a year with better runoff.

The summer pasture grazing period is naturally the prime time for water quality concerns. Livestock water demand increases with temperatures and at the same time quality deteriorates from consumption and evaporation. Without adequate rain, undesirable elements in the water become more concentrated.

As well, summer promotes higher bacteria growth that affects quality. Among the concerns is cyanobacteria, also referred to blue-green algae. Clark said it could be confused with beneficial algae so she recommends confirmation of the contaminant before treating the water.

CowBytes and Alberta Agriculture are good sources of information about water quality, as are regional agricultural specialists, said Clark.

Grant discussed the economics of water testing. Given that calves with access to clean water are on average 18 pounds heavier at weaning, the return on investment in good quality water is considerable, she said.

Even so, data from the 2017 Western Canadian Cow Calf Survey showed 59 percent of producers never test their livestock water.

Data compiled by Cows and Fish indicates that, if given a choice between water from a trough or from surface water such as a dugout or stream, cattle will choose to drink from a trough eight out of 10 times.

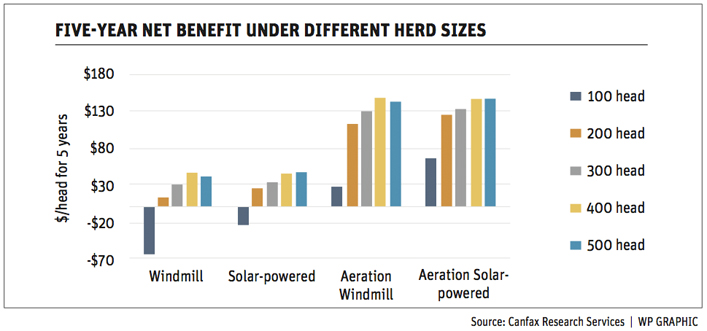

Grant compared the costs of various systems that improve water quality, such as wind or solar-powered pumps, aeration and geothermal systems. The time required to pay for system upgrades, in terms of profits from calf sales, varies with the market price in any given year.

Some provincial grants are available to help with costs, particularly for smaller herds, she said.

Grant suggested that producers test dugout water at the start of the season to get a base line and then test again later in the season if there’s a risk of quality deterioration.

Alberta Agriculture has a website to help producers interpret water test results. Livestock specialists across the Prairies can also provide assistance, she said.

Sulfate risk

Risks to cattle increase as sulfate concentrations in water rises.

Concentration level of <500 mg/litre: Satisfactory

Concentration level of 500-1,000 mg/litre: Potential for sub-clinical mineral deficiencies

- Especially high performing cattle.

- Mineral supplementation & monitoring important.

Concentration level of 1,000-2,000 mg/litre: Caution

- Potential for clinical deficiencies

- Chelated mineral supplementation at high end.

- Performance & health status decline likely.

Concentration level of >2,000 mg/litre: Risky

- Severe clinical deficiency likely.

- Chelated mineral supplementation & monitoring necessary.

- May or may not respond to supplementation.

- Performance & health status effects pronounced.

- Risk of death especially high in performing cattle under stress.