On the Farm: The Whites grow a diverse rotation of crops, raise bison and aim to reduce inputs as much as possible

About three years ago Brooks White had an “aha” moment that changed his life, or at the very least, changed how he views farming.

White was browsing on the internet when he came across a phrase that he hadn’t heard before: regenerative agriculture.

Suddenly, everything made sense.

“I saw that and (said), ‘that’s it, that’s what we want to do.’ ”

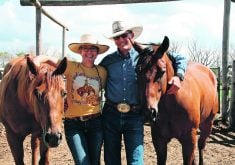

Brooks and his wife, Jen, farm near Lyleton, Man., in the extreme southwest corner of the province.

They operate a bison and grain farm called Borderland Agriculture, so named because of the proximity to the Saskatchewan and North Dakota borders.

Read Also

Nutritious pork packed with vitamins, essential minerals

Recipes for pork

They raise around 600 bison and have a land base of 7,500 acres with 5,000 acres dedicated to annual crops.

Brooks was raised on the same farm, but Jen grew up in Minot, N.D.

They met because Jen’s mother married a farmer from the Lyleton area. In 2001, Jen was visiting her in Lyleton when someone invited her to a social.

“I said, ‘what’s a social?’ ” Jen recalled.

She drove up from Minot for the event and was introduced to Brooks. By 2004 they were married.

They now have two children: Sawyer, 7, and Piper, 4.

Jen may have grown up in the city but she now understands the perks of the farm lifestyle.

“I like the flexibility and just being able to be with your family. Everybody is together.”

Brooks was involved in the family farm near Lyleton at an early age. He always knew he would take over the farm from his father, Ron, and become the fifth generation of his family to farm the same land.

“I never had an off-farm job. Just always worked for dad on the farm.”

He enrolled in the University of Manitoba’s ag diploma program in the 1990s and while there developed a farm plan, which involved adding bison to the Lyleton operation.

In 1999, Brooks and Ron followed through on the plan and bought 33 bison heifers.

The farm became a mixed operation, but a number of years after adding the bison, Brooks realized something was wrong.

Ron had been practising zero tillage since the 1980s, but the soil was less productive than expected.

“As grain farming progressed towards higher inputs … (the) profitability just wasn’t there. Zero-till alone didn’t appear to be enough to build soil organic matter,” Brooks said.

“(But) on grain land where we had been grazing the bison, we were seeing increased nutrient levels, and organic matter was building. We could farm these fields with less inputs.”

Brooks officially took over the farm in 2012 and continued down the path of cutting input costs by improving soil health.

He integrated the bison into a diverse cropping system, including cover crops, soybeans, fababeans, peas, canola and lentils. Then he began experimenting with intercropping and tried to extend the grazing season for the bison with the goal of grazing them 365 days of the year.

Brooks was doing all this when he stumbled upon the phrase “regenerative agriculture.”

“We had been trying to figure this system out on our own. Once I got online, (I) learned how many others were trying to do the same thing. Then we were able to make faster advancements,” he said.

”We are currently in a transition phase. I don’t feel we can turn the switch off overnight to move to this type of a system, but it’s something that we’re committed to.”

Cutting inputs and talking about “systems” sounds a lot like organic farming, but Brooks isn’t interested in that approach because he believes pesticides and fertilizer are useful tools.

“I want to have those as options, going forward,” he said.

“If we’re going to have an outbreak and lose a crop because something moves in, I want that in my toolbox.”

However, Brooks is convinced that using fewer inputs is key to making money at farming.

“On my numbers, we’re showing we can be more profitable in this regenerative system,” he said.

“We may be looking at reducing yields, but being more profitable while doing that.”

Together, Jen and Brooks crafted a vision statement for their farm. It’s posted on their website at www.borderlandagriculture.com/.

In brief, their vision is to regenerate the soil, regenerate their business and regenerate the agriculture industry.

Publicly sharing their goals was a deliberate choice because they believe they’re part of a larger movement within agriculture.

“Promoting (regenerative ag) is part of our vision,” Brooks said.

“Not to put anybody else down…. We’re just putting it out there … what is working for us and these are the reasons we think it’s working for us.”

Others in Manitoba’s agricultural industry have noticed what the Whites are doing.

In March they were recognized as Manitoba’s Outstanding Young Farmers for 2018.

They will compete in the national OYF competition this fall in Winnipeg.

What is regenerative agriculture?

The website for Regenerative International, a non-profit organization, defines regenerative ag as “a holistic land management practice that leverages the power of photosynthesis … to close the carbon cycle and build soil health, crop resilience and nutrient density.”

In practice, it involves:

- zero or minimal tillage

- cover crops and diverse crop rotations

- compost to restore soil

- microbiology

- grazing practices that stimulate land productivity

Source: Regenerative International