The winter was long. Hay is in short supply. It will be tempting for producers to put the cows out on grass as soon as green appears in pastures.

Resist that urge, says range management extension specialist Nadia Mori.

Grazing too soon weakens both tame and native pasture and will shorten the grazing season.

“We’re coming out of the winter, and the animals haven’t seen anything green and they’re just racing for every little bit of green that comes out,” said the Saskatchewan Agriculture agrologist.

Read Also

Farming Smarter receives financial boost from Alberta government for potato research

Farming Smarter near Lethbridge got a boost to its research equipment, thanks to the Alberta government’s increase in funding for research associations.

“For the plant, that’s one of the most stressful times. Going one week too early could make you lose three weeks in the fall, just because the plants never had that time to really replenish after spring growth.”

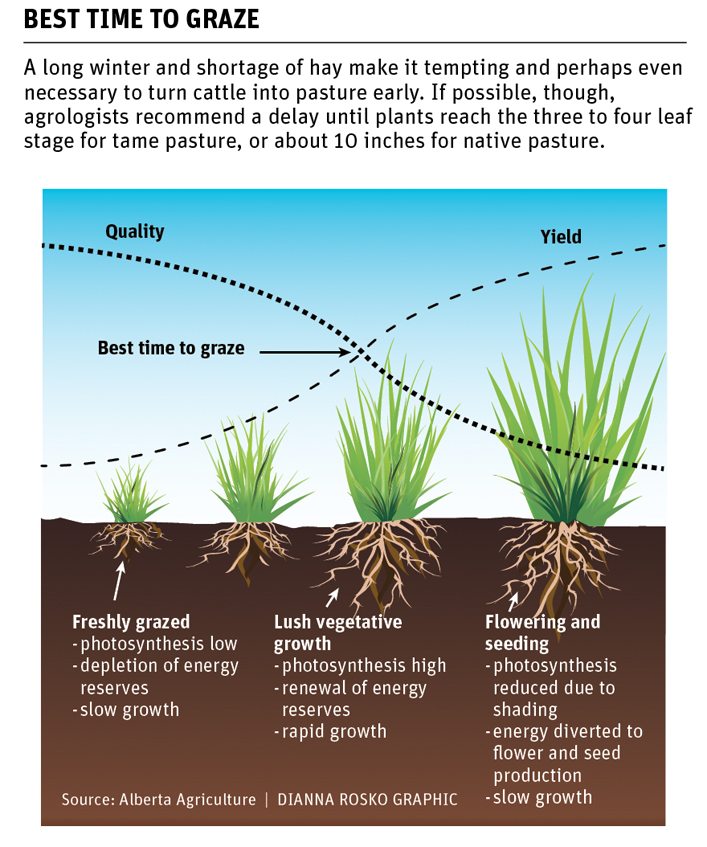

Ideally, producers wouldn’t graze tame pasture until plants reach the three to four leaf stage and would leave native pasture alone until at least mid-June.

But reality bites, as they say, and given the conditions, cattle may have to go out early, hopefully on a field that was well rested the previous year.

“If you don’t have that, you’re going to just have to make a decision and pick sort of a sacrificial field that’s going to be the one you’re going to go on,” said Mori.

“We all understand that there are times and years when we do have to disregard the best management guidelines, but then that needs to be part of future management.”

Mori said it would be better to graze tame pasture early, as opposed to native pasture, because it will recover quicker from pressure. As well, tame pasture can be rejuvenated or even re-seeded if necessary.

Karin Lindquist, a beef and forage specialist with Alberta Agriculture, said she knows ranchers are “chomping on the bit” to start grazing, but starting too early has a cost.

Grazing before the three to four leaf stage reduces plants’ ability to replenish their energy through photosynthesis. That forces them to use energy reserves in the roots, halting further root growth.

Should the Prairies experience another dry summer, those plants will have less ability to withstand adverse conditions.

“If the plants are going to be grazed so low that there’s not much leaf area there, then that means that there’s going to be a negative effect on the roots, and the less root mass there is, the less hardy those plants are going to be,” Lindquist said during an April 19 webinar.

“That’s something to think about, if producers are thinking about putting out their animals just when a little bit of green is starting to come out.”

Mori said tame and native pasture must be treated differently for best results.

Native pasture evolved with periodic but intense grazing events followed by long rest. It may not be possible for producers to emulate that.

“The reason why we usually give the recommendation to wait until late June is that there’s still the practice out there of doing season-long grazing. There’s a lot of debate around it, but personally, as a range agrologist, it’s not something that we recommend.”

Native prairie didn’t evolve under the kinds of grazing pressure frequently put upon it, she added. That’s why it is important to allow native grasses the time and space to regrow, grazing it only once a year, if possible.

Tame pasture, in comparison, can be grazed multiple times in a season.