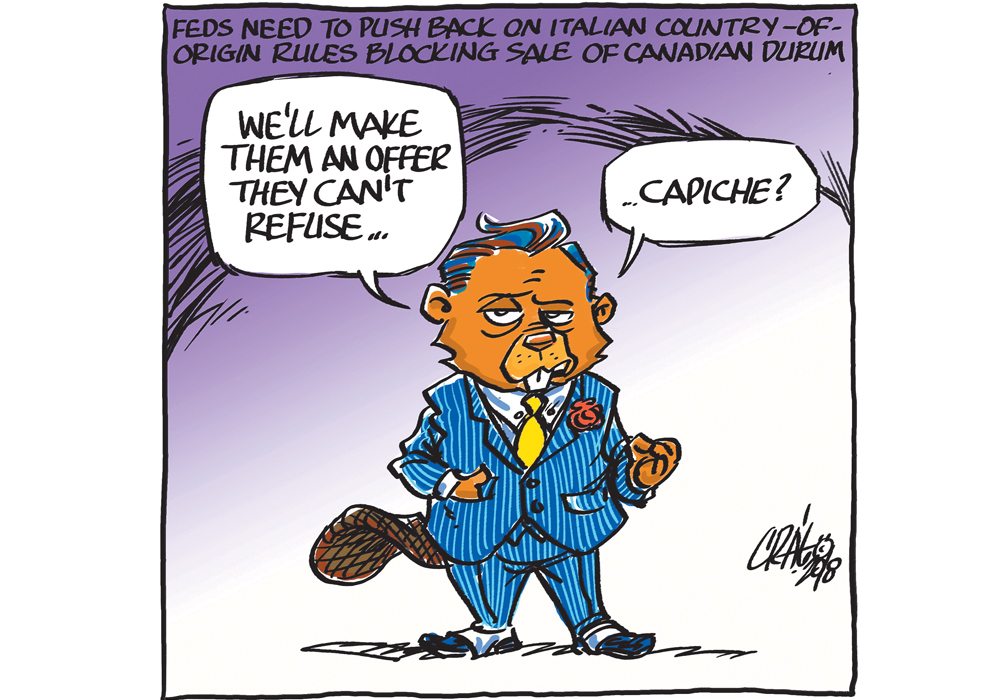

Since January, Cereals Canada has been calling for the Canadian government to formally lodge a complaint to the European Union or the World Trade Organization about Italy’s campaign to undermine Canadian durum.

It is time to move on this.

It’s not just a matter of fairness. Canada risks gaining a reputation as a country that can be pushed around, and that must stop before other countries follow Italy’s example.

Italy is using shady tactics to curtail Canadian durum imports, despite that country’s participation in the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between the European Union and Canada.

Read Also

Proactive approach best bet with looming catastrophes

The Pan-Canadian Action Plan on African swine fever has been developed to avoid the worst case scenario — a total loss ofmarket access.

Italy is using country-of-origin labelling combined with a ruthless smear campaign by farm groups on the so-called dangers of Canadian durum to shut the crop out of Italian markets.

It has worked. Canada typically produces a $1.3-billion durum crop annually and Italy usually imports 20 to 25 percent of that, which equalled about $321 million in 2016 and $447 million in 2015.

But since COOL regulations were enacted in mid-February, virtually no Canadian durum is going directly to Italy.

Canada went through this for years in the United States, when almost six years of COOL on Canadian beef and pork cost Canadian producers upwards of $1 billion a year, before World Trade Organization rulings forced the U.S. to stop.

In Italy, COOL has two main effects: it encourages consumers to bypass Canadian durum in favour of Italian, which flies in the face of trade agreements, and it makes Canadian durum more costly because segregation practices are expensive.

As well, some farm groups are denouncing the safety of Canadian durum citing glyphosate and deoxynivalenol issues. Two shipments of Canadian durum have been seized at Italian ports, leading to headlines such as “Canadian wheat contaminated, large-scale seizure in (the port of) Bari.”

But testing showed residues were well within maximum residue limits. Glyphosate is used as a pre-harvest product in some durum, but last year it wasn’t common due to the dry summer. Glyphosate is facing heavy scrutiny in Europe and is banned from pre-harvest use on wheat in Italy, so it is a convenient target for a public relations campaign.

When the labelling campaign was being considered in July 2017, Italian farmers demonstrated near the country’s parliament in Rome carrying signs that said, “We don’t want Canadian wheat with glyphosate.”

It is a ruse to undermine the confidence in Canadian wheat, which is typically high quality, and thus provides competition for Italian domestic durum.

At least one trade observer has said other countries might feel they can copy Italy’s practices in an environment that is becoming increasingly protectionist.

Why would the Italians do this, when their country grows only about 60 percent of the durum it needs for pasta? Some Canadian ships are arriving with durum at the same time Italian farmers are selling their grains, and Canada’s durum, especially from last year’s crop, is high quality, so it is in demand by millers and flour makers. But Italian farmers are wary of the competition.

Regardless, it’s time to fight back. Canada can lodge complaints under CETA and WTO rules, but if it wants to make a point it can also start talking about the value of Italian wines imported to Canada, which is roughly the same as pre-COOL durum exports.

No doubt Italian grape producers and Canadian wine consumers would shudder. So be it. It’s time for Canada to toughen up on these kinds of obstructionist trade practices.

Karen Briere, Bruce Dyck, Barb Glen, Brian MacLeod and Michael Raine collaborate in the writing of Western Producer editorials.