BRANDON — Most surface drainage work performed on the Prairies until recently was based on the “deep thinking school of thought” of the 19th century — but the deep thinking scholars are gone.

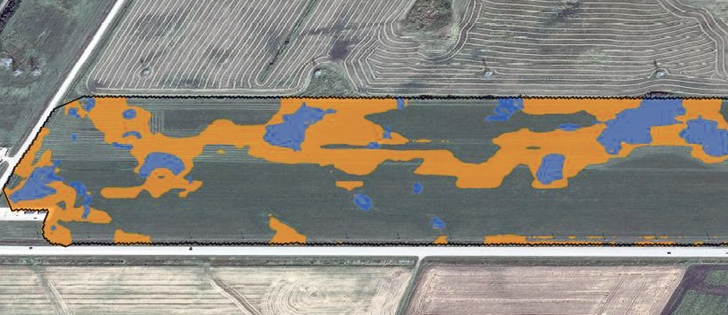

Two changes have taken place recently. First, in many people’s opinion, the biggest step has been affordable RTK technology, which allows farmers to build more accurate elevation and prescription maps. A number of user-friendly programs are available, giving farmers the tools to do the planning and execution themselves.

Secondly, there’s a new concept in managing water flow, best summarized as “don’t be in such a big hurry to get rid of the water.”

Read Also

Growing garlic by the thousands in Manitoba

Grower holds a planting party day every fall as a crowd gathers to help put 28,000 plants, and sometimes more, into theground

Farmers have stopped gouging out those deep implement-busting ditches of the 1800s. Instead, they are scratching gradual, meandering surface drains with just enough grade to slowly move water to the edge of the field. The modern prairie drain is shallow enough to farm through without busting up the equipment, eliminate erosion from fast-flowing water and increase the number of acres that can be farmed easily.

University of Manitoba soil scientist David Lobb said a variety of water management practices that available.

Lobb is a well-known researcher who delves into biophysical processes within landscapes, particularly soil movement by tillage and erosion. His lab is the largest in Canada and the second largest in the world for the assessment of soil erosion and sedimentation using radionuclides.

In an interview following a presentation earlier this year, Lobb commented on the prospect that enough slow-moving water might percolate into the soil in significant volume to turn the tide in a dry growing season.

“That’s not going to work,” Lobb said.

“Between 80 and 85 percent of the moisture we receive on our fields is snow melt. When that snow melts, the ground is still frozen. Or if we’ve had fall rains, the ground is both frozen and saturated. It’s like concrete. That ground is totally impermeable to new moisture. If you have these extremely shallow drains, the water will still be sitting there when you should be seeding. It would depend very much on the soils. There may be some locations where that would work.”

He said the main reason we have spring runoff is that snow melt water cannot infiltrate the soil. However, there are ways to make changes.

If you increase soil organic matter and improve soil structure, you will gain better infiltration of the snow melt and any rainfall during the growing season. If you can improve infiltration throughout the landscape, then less water and fewer nutrients are flowing downstream.

“Let me give you an example,” he said.

“At the St Denis national research area 40 kilometres east of Saskatoon, the Canadian Wildlife Service converted cropland back to grassland. All the wetlands dried up.

“With a grassland cover, water infiltrated the soil. Before, it ran off into the dugouts and potholes. Without runoff, they lost their source of water. Also, the snow was being captured in the uplands, so when it melted, the water soaked in and the local vegetation used that moisture.

“The hydrology of these systems can be fairly sensitive and easily manipulated by man. One of the best things we can do is to grow more permanent vegetation, trap more snow and improve the conditions for water infiltration. If we do that on just a little bit of the land surrounding a wetland, you can improve the hydrology of that wetland.”

On a related topic, Lobb said low-level back-flood retention dams are a proven way of keep water on the landscape in dry years, but they’re relevant only in beef-growing areas.

“These dams do allow percolation of water into the soil in the immediate area, but they’re only relevant in cattle areas, to ensure there’s green forage for livestock.”