Loblaw’s bread price-fixing scheme likely had little to no effect on farmers, said a food supply chain expert, but he said the scandal has enhanced feelings of mistrust.

Sylvain Charlebois, a professor in food distribution and policy in the faculty of agriculture at Dalhousie University, said the scheme was likely used to control market conditions, where prices could have been raised to increase profits or lowered to drive out competition.

“For farmers, it just gives them one more reason to hate grocers,” he said. “I highly doubt they were affected by this scheme, however, Loblaw’s is on the front line representing the end-product that farmers work hard to produce, and they (farmers) shouldn’t be tainted by what happened.”

Read Also

Farming Smarter receives financial boost from Alberta government for potato research

Farming Smarter near Lethbridge got a boost to its research equipment, thanks to the Alberta government’s increase in funding for research associations.

In mid-December, Loblaw admitted to being part of a 14-year arrangement, from 2001 to 2015, with parent company, George Weston Ltd., that involved purposefully setting the price of bread in its grocery stores.

Executives with both companies have said they didn’t know the scheme was occurring and reported it to the Competition Bureau as soon as they found out.

As well, they alleged that other major grocers have been involved. The allegations haven’t been proven in court and no charges have been laid.

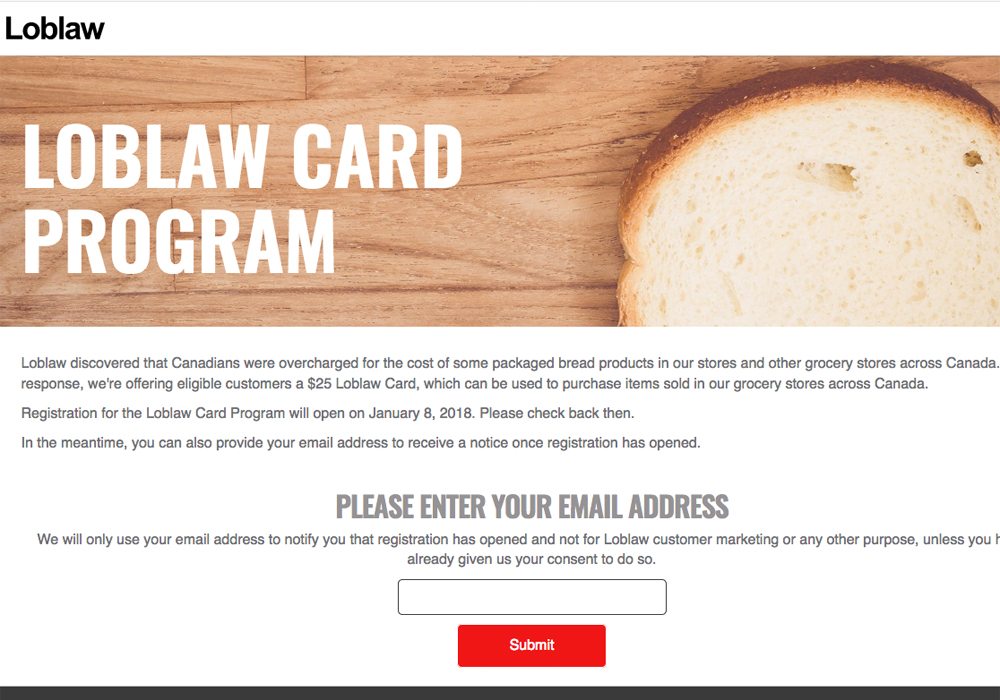

Loblaw will be immune from receiving criminal charges because it tipped off the bureau, and the company is offering $25 gift cards to consumers as a gesture of good will.

Charlebois referred to the gift-card offering as “window dressing.”

“My guess is the gift certificate that went out is a distraction,” he said. “But this is seriously disturbing. It’s the largest retailer in the country, breaking the law for 14 years.

“This sends a strong signal that perhaps the industry be more careful in making sure it does follow the rules because we are dealing with a handful of major grocers and a handful of major processors.”

While Charlebois argued that consumers weren’t gouged, because most grocers sell bread at a loss, Statistics Canada data paints a different picture.

According to the consumer price index, which compares the cost of a fixed set of goods over time, it appears to show the price of bread climbing disproportionally during the price-fixing scheme.

Throughout the 1990s, bread prices were increasing at a pace on par with other goods. But when the scheme began, in 2001, bread prices climbed exponentially while the price of other goods grew marginally.

The data doesn’t put a dollar figure on the increase in bread prices, but does show how much prices changed when compared to other food items.

Still, other factors have to be taken into account, Charlebois said.

For instance, a loaf of bread today is cheaper than it was in 2013, he said. As well, the price of some bakery items doubled in 2007 and 2008 when wheat prices reached high levels due to strong global wheat demand.

“Higher bread prices at the time was not just unique to Canada,” he said. “Many countries were affected.”

He said he doesn’t think the price-fixing issue will disappear anytime soon.

“There is going to be a lot of discontent in the industry about what happened,” he said. “Hopefully it will make the industry stronger and more honest. That’s what Canadians deserve, that’s what farmers deserve, and that’s what everyone else in the supply chain deserves.”