Everyone knows that the tax man giveth and the tax man taketh away.

But in the case of carbon tax, who will giveth the most?

Farm economists who spoke at the Prairie Agriculture Summit in Saskatoon last week delivered a generally positive message about carbon taxes, suggesting that financial rewards realized by Canada’s agriculture sector could outweigh financial penalties.

But like most taxes, the devil will be in the details, they added.

In theory, farmers may benefit financially by adopting farm practices that reduce emissions. However, they could also see higher prices for many of the goods and services they consume.

Read Also

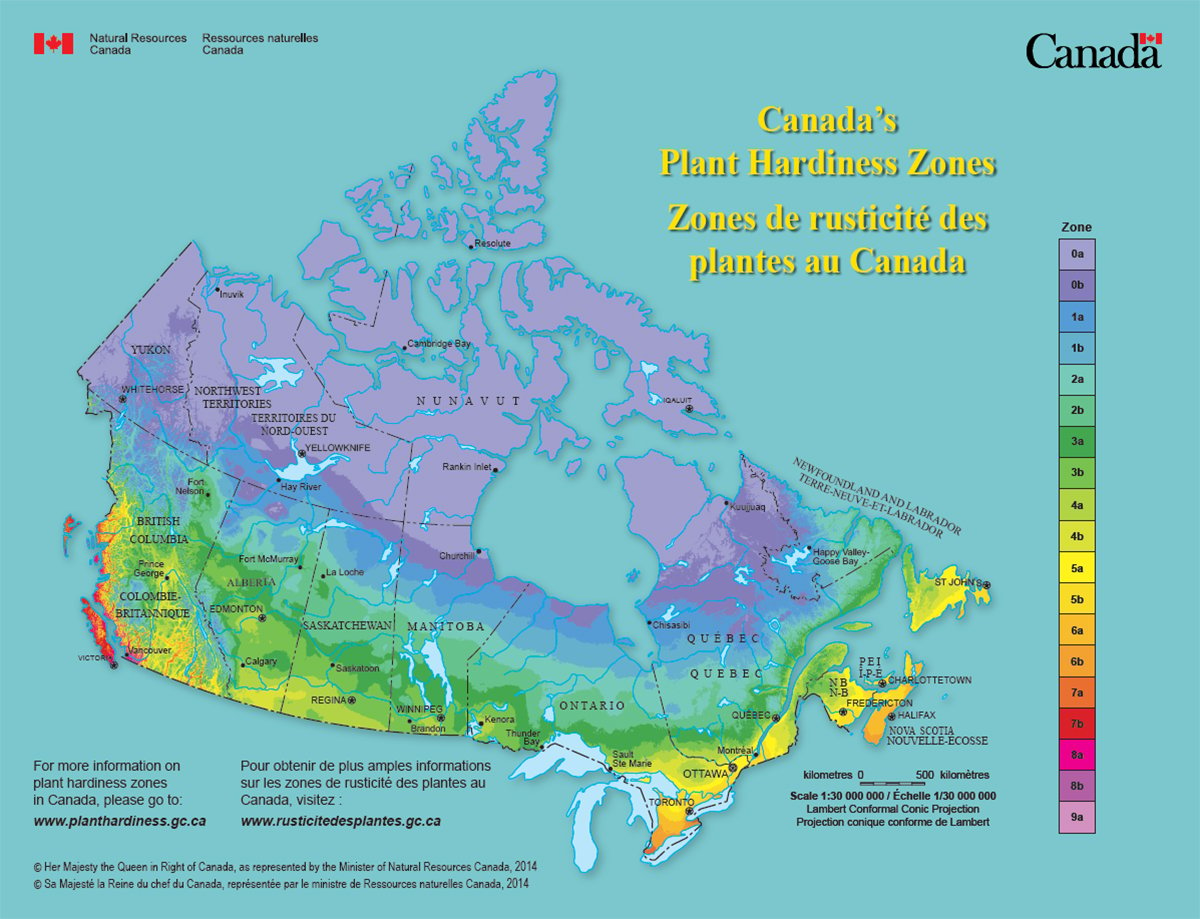

Canada’s plant hardiness zones receive update

The latest update to Canada’s plant hardiness zones and plant hardiness maps was released this summer.

“The idea that one particular sector of the economy (agriculture) can be completely exempt from a tax that’s going to affect the entire economy is a fallacy,” said Tristan Skolrud, a carbon tax expert and assistant professor at the University of Saskatchewan’s agricultural and resource economics department.

Skolrud presented the following scenarios, based on a federal carbon tax rate of $10 per tonne in 2018 that rises to $50 per tonne in 2022.

- Grain drying: Natural gas prices are a significant factor in determining grain drying costs. If a grower removes 2.5 pounds of water from every bushel of grain, then the fuel-only cost of drying that grain could increase by 50 percent over five years. Skolrud said the fuel-only component of drying could rise to three cents per bushel, or $1.93, per acre in 2022, up from two cents per bu., or $1.29, per acre in 2018, assuming a natural gas price of $3.65 per gigjoule and an average yield of 64.5 bu. per acre.

- Trucking: Higher fuel costs paid by trucking companies will likely be passed on to growers that pay to have grain trucked to market. Based on diesel costs of 90 cents per litre, fuel economy of 33 litres per 100 kilometres and a hauling capacity of 1,000 bu., the fuel-only component of trucking costs could increase to 3.4 cents per bu. per 100 km in 2022, up from three cents per bu. per 100 km in 2018.

- Rail freight rates: Fuel is a major component of rail freight costs. Currently, rail freight rates on much of the grain produced in Western Canada are regulated through maximum revenue entitlements, also known as the revenue cap. The implementation of a carbon tax will result in shipping costs for railways and are therefore likely to be reflected in a higher revenue cap, beginning next year.

- Input costs: The prices of basic farm inputs, including nitrogen fertilizers, potash and chemicals, could increase at the consumer level, depending on where those inputs are manufactured. The extent to which prices rise will depend on whether farmers have access to substitute products that are manufactured in jurisdictions that do not have a carbon tax. For example, if a Canadian fertilizer manufacturer pays a carbon tax of $50 per tonne and a competing American manufacturer pays nothing per tonne, then Canadian fertilizer manufacturers may be forced to absorb a portion of the extra tax cost rather than passing it on to consumers in order to remain competitive.