Quagga mussels, an invasive aquatic species, are moving ever closer to Alberta.

Larvae of the mussels, called villagers, have been found in Montana’s Tiber reservoir east of Shelby, making the nearest point of spread only 80 kilometres away from Alberta’s waterways and vast irrigation systems.

Tim Romanow, executive director of the Milk River Watershed Council, said quagga larvae were confirmed in Montana last week. The Tiber reservoir connects to the Marias River system, which flows into the Missouri River.

It is too close for comfort to the Milk River and St. Mary’s River systems, he said.

Read Also

Farming Smarter receives financial boost from Alberta government for potato research

Farming Smarter near Lethbridge got a boost to its research equipment, thanks to the Alberta government’s increase in funding for research associations.

“I think it’s the first positive that’s been found in Montana,” said Romanow.

“If it does get into the upper St. Mary’s or gets into the upper Milk River … it’s a game changer. (There’s no) stopping it from getting into all the irrigation systems and water treatment plants basically from Cardston east to Medicine Hat.”

Alberta government estimates show invasive mussels could cost the province $75 million in damages annually. The irrigation industry alone could see $8 million in annual costs to combat the mussels.

A news release issued by Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks said that department and the Montana Invasive Species Advisory Council are checking the shores of the Tiber and the Canyon Ferry Reservoir near Helena for signs of adult quagga and zebra mussels.

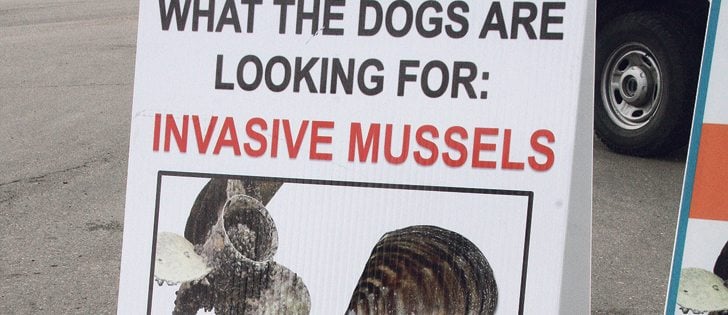

Mussel sniffing dogs trained in Alberta are being used in the search.

Eileen Ryce, FWP fisheries division administrator, said Nov. 14 that this is Montana’s first sign of the mussels, which have invaded much of the United States and the Great Lakes and are now in Lake Winnipeg.

She said it is possible but unlikely to have mussel larvae and not adults.

“By finding (veligers), what it tells us is there’s either a reproducing population of adults or that those veligers have been dropped into the lake from a boat, for instance, that may have had positive water in their bilge. It’s likely that there is a reproducing population in the lakes and we just haven’t located it yet.”

Adult mussels do not reproduce in cold temperatures, so Ryce said an inter-agency response team has been formed to plan a response.

“We’re looking at both developing a plan for containment and a plan for control. We’re not really at the point where we know what we’re going to be doing but we’re going to be working on those over the winter and have something in place soon.”

Ron McMullin, executive director of the Alberta Irrigation Projects Association, said the discovery means that Western Canada has lost its buffer zone against invasion.

“We were quite proud of having what we call a perimeter, where Oregon, Washingon, Idaho, Montana … and then us and B.C. and Saskatchewan were mussel free. So we had this nice little perimeter and we could help protect each other. Our perimeter is breaking down, so that is distressing.”

Many Albertans cross the border into Montana for fishing and boating. The province and mussel-free states have promoted a “clean, drain, dry” program for watercraft and there are mandatory inspections at the international border.

However, frequent boat and watercraft traffic increases risk of contamination because villagers are microscopic and adult mussels are about the size of a thumbnail.

“Especially being that close to home, we’ve got lots of weekend warriors who run down there,” said Romanow.

“The Montana folks have done some sampling in the lower part of the Milk River and the Marias to see if (invasive mussels) are showing up in samples down there and its been negative so far, but my concern is … there’s a lot of traffic locally that wouldn’t necessarily be going through an inspection station on the Montana side.”

McMullin said Alberta irrigators are on alert to mussel invasion, which is why they contributed to the sniffer dog training program and signage about the threat at most Alberta lakes commonly used for recreation.

Irrigators are also monitoring Alberta Agriculture research into potash as a control method. Tests show it kills invasive mussels but also kills native mussel species.

The irrigation system has 4,000 km of pipelines plus other infrastructure, so blockage by mussels, which multiply rapidly, is a major concern.

Quagga and zebra mussels that have invaded other parts of North America have wrought havoc on water systems.

“This is costing hundreds of millions of dollars stateside for control efforts,” said Romanow.

“Some municipal waterworks in some areas, they’ve basically had to build a double system in order to accommodate for shutdowns for maintenance to clean quagga out and still have water coming through their systems.”

The invasive mussels also destroy fish habitat, other aquatic ecosystems and ruin beaches with accumulated sharp shells.

Romanow and McMullin both emphasized the need for people to be aware of the threat, comply with border inspections and clean their equipment. Mussels can travel in bilge and ballast, water buckets and bait, and cling tenaciously to surfaces.

“Honestly, I think the best thing we can do is just to continue to promote the clean, drain, dry program and we can reassure people that there has been some really strong monitoring and awareness work that’s been happening in Alberta,” Romanow said.

“But this is a big scary one. That’s jut too close to home when it’s literally an hour across the border from us.”