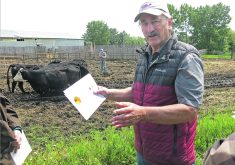

LUNDBRECK, Alta. — The cattle are DNA tested, their expected progeny differences analyzed and from that, a breeding program is developed.

That attention to genetics allows the Lynch Stauntons to accurately select for desired traits in the cow-calf herd on their Antelope Butte Ranch north of Lundbreck.

Hugh Lynch Staunton and later his sons Jim and Tom have been collecting data on their herd since the 1980s. However, the more recent ability to gather DNA data and accurately identify the sire of calves has led to a selection index they use to develop their herd in the desired direction.

Read Also

Beef check-off collection system aligns across the country

A single and aligned check-off collection system based on where producers live makes the system equal said Chad Ross, Saskatchewan Cattle Association chair.

“When we started selecting specifically on performance numbers, we ended up getting average looking cattle,” Jim said while standing in a foothills pasture during an Alberta Agriculture genomics event.

“They’re just ordinary cattle and we’re not going to get any real monsters. We’re not going to get anything really showy. We’re getting cattle that we don’t have to touch and can live on cardboard.”

Breeding by the numbers can have its drawbacks. Jim said it led to cattle that he deemed were slightly too small, which they remedied by tweaking the breeding program and bull selection.

“I think that’s important, to have a moderately sized animal, but I think we just went too far. We’re going back in the other direction now.”

The herd is expected to graze throughout the year and get at least half its needed nutrition from winter grazing on the hardy grasses along the foothills and eastern slopes of the Livingstone Range.

Cows that can look after themselves and their calves while achieving certain weights and carcass values are the primary goal.

“Mainly what we want to do is to continue getting a cow that you don’t have to touch, and something that will fit our environment and fit our market well,” said Jim.

“(It’s) more important than carcass traits because I think as soon as you try to genetically get to hit some market, by the time you get there, the market will have changed. So I think it’s more important to worry about profitability on your own place, in your own environment, under your own management.”

Tom, who is with Livestock Gentec at the University of Alberta, told those on the tour that patience is a virtue when it comes to genetic selection.

It takes time to see the results of a breeding program — at least two years to a first calf and then several years beyond that.

“We do make tweaks to the selection index as time goes on, and the genetic evaluation is sort of revamped every five years,” Tom said.

“The trick is that in tracking genetic improvement, you have to kind of wait, give it time, that five to 10 year time frame. And the thing is, we hate waiting to see if we’re making any improvements, so we have to be very patient when we’re using selection indexes.”

Knowing the DNA and indicators from sires improves the quality of data by 50 percent, said Tom. Blending that data with female genotypic values could result in accuracy of up to 60 percent in the progeny.

Quality of genomics information depends on the size of the population tested, the number of DNA markers identified, the number of animals with available genotypes and the integrity of the genomic records, said Tom.

However, this data allows breeders to more accurately predict birth weights, weaning weights, yearling weights and back fat, while avoiding birthing problems and genetic defects.

Larry Sears, who operates the Flying E Ranche near Stavely, Alta., has been collecting carcass data on his animals for more than 10 years.

The data has resulted in 67 percent of the cattle in his feedlot grade AAA, compared to 54 percent five years ago.

Sears uses IdentiGEN, the company that does genotype assays using DNA samples. His operation has had DNA sampled from calves and bulls for the past three years.

“The DNA samples through IdentiGEN gave us some insight as to what the bulls were doing on any particular cow,” said Sears.

The sire genetic information, when coupled with EPDs, has led to higher carcass grades in offspring.

Sears also attributes improvements to low-stress weaning, getting weaned calves on feed quickly through the use of creep feed and applying implants at weaning rather than at branding.

The latter is a result of advice that showed implants are better applied when calves are on a rising plane of nutrition.