Holistic approach | Cattle producer loves cattle and grass and works to improve both through breeding and management

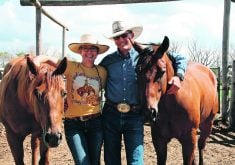

VERMILION, Alta. — Connie Smith loves the Alberta country home she shares with fiancé Brian Chrisp, and both enjoy the busy lifestyle of their respective careers.

The couple, who has been together for five years, met at Smith’s Riverside Hair Design, where Smith cut Chrisp’s hair.

She helps wherever needed at Misty Hills Charolais near Vermilion, but leaves the heavy lifting to Chrisp, who she describes as “a go-getter.”

Chrisp grew up here on what he called a subsistence farm with intentions to become a veterinarian. The name Misty Hills comes from the hilly terrain that many mornings is thick with fog.

Read Also

Starting a small business comes with legal considerations

This article sets out some of the legal considerations to start a business to sell home-grown product, such as vegetables, herbs, fruit or honey.

This warm day, Chrisp shows off animals grazing belly deep in grass and pastures with a dense trash cover.

“When looking at the grasses in pastures, it goes without saying it’s working,” said Smith, who was raised on a grain farm near Govan, Sask.

“That’s his thing. He knows what he’s doing. It would be like having him ask me if I should perm this lady’s hair.”

Chrisp owns eight quarters and rents another seven quarters of pasture for the 150 purebred cows he keeps on abundant stands of grass. He winters about 350, buying most of his feed, and sells purebred bulls at a sale in April each year.

“There’s no crop farmer in me. I love grass and cattle,” said Chrisp, who has also taught farm management and cow-calf production at nearby Lakeland College.

“I like cows rather than tractor operations.”

He adopted holistic management practices, including shorter grazing periods and longer rest periods, to better manage grass and extend the grazing season.

“I have grass stands that were seeded in 1983 still productive,” said Chrisp.

The cows were last fed April 30, and he will start feeding them again in November, he said.

He liked Charolais because of the “big performance difference compared to British cattle.… Through time, we refined and improved calving, moderated the size and found a premium price for Charolais cross calves.”

Chrisp, who has two adult daughters and two grandchildren from his first marriage, studied agricultural economics at the University of Alberta.

“That was a useful tool on the farm,” he said of his skills in business management, the people he met, the networks he formed and new ideas that arose.

Chrisp works with crop farmers to graze what’s left on their fields after harvest as well as their slough bottoms.

He said his cattle are so used to being moved that they generally come when called.

“Quads are my horse,” said Chrisp of the hundreds of hours he spends straddling the all-terrain vehicle.

He is part of a management group that focuses on crops, prices, markets, goal setting and decision-making.

“It’s super helpful, networking, making friends and trading management ideas,” he said.

Chrisp said the cattle business is good this year.

“The cattle market is setting continual records, prices we couldn’t have comprehended a few years ago.”

The previous day, he sold a 1,700 pound cow for hamburger for $1.30 a lb. for $2,200.

“Her value was half of that a year ago,” he said, noting the cattle industry has lost a generation of producers due to recent tough times.

He thinks better prices might bring people to the business.

“This fall, they will get paid for the efforts of the past,” he said.

“Good prices definitely put the romance back in the cow business.”

He survived the tough years of closed borders and BSE by maintaining a seed stock base, renting out bulls and keeping the herd intact.

“People were not willing to buy but they were willing to lease them,” said Chrisp, who offered 100 of his own bulls.

That leasing business continues on a smaller scale today.

He expects calf markets to be strong for at least the next five years, barring any political interference, he said.

In addition to Smith, Chrisp also gets help from a retired farmer who watches over the place when the couple takes holidays, volunteers at the local fair or manages the annual bull sale in April.

The sale, which is the second biggest Charolais bull sale in Canada, features animals from four producers. It’s held at the Nilsson market in town and sells 100 bulls, almost half of which come from Misty Hills.

He halter breaks the bulls before sales to make them more manageable, something buyers appreciate.

He prefers hiring women to halter break his bulls the low stress way, using methods learned from mentors like Bud Williams.

“Girls outthink them and most guys want to outpower them,” he said.

Chrisp is a past-president of the now disbanded Western Canadian Fairs Association, and he and Smith have been involved with the Vermilion fair for many years.

He’s especially proud of the agricultural content and youth base of volunteers at the rural fair, which features events from tractor pulls to livestock shows.

He compared it to Edmonton and Calgary exhibitions that draw crowds that don’t exceed their populations.

By contrast, Vermilion, population 4,500, draws 24,000, or five times its population.