EDAM, Sask. — Glen Foulds takes in a sweeping million dollar view from the porch of his rustic wooden cabin high above the North Saskatchewan River.

“My best holiday is just being out here and sitting on my chair watching the river and the animals,” he said of the farm, aptly named Paradise Acres.

Branding irons and antlers decorate the outside walls, while inside the two-storey home, an antique cook stove and oven are fueled by deadwood scattered around the half section farm.

The Foulds family, which has called this remote setting home for more than a century, grows feed and maintains pastures for a small commercial cow-calf herd and horses used for hauling.

Read Also

Nutritious pork packed with vitamins, essential minerals

Recipes for pork

They trace their ancestry back to Hudson Bay surveyor Peter Fidler from England, who married Mary Mackagonne, a Swampy Cree, and had 14 children.

Glen’s grandfather, Robert Foulds, came to Edam from the Red River settlement near Winnipeg, although he initially got only as far as Prince Albert, where he spent the winter hunkered down in dry holes along the riverbank.

Glen’s uncle, John Foulds, actually owned the farm, but said his father, George, was always involved.

“My dad never really owned, but (the family) farmed together,” said Glen, who grew up here as one of nine children and acquired the farm from John in 1964.

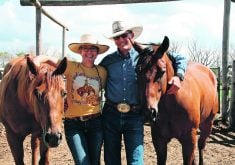

Today, Glen and his wife, Ilene, split their time between a modest home in Edam in winter and the farm in the growing season.

Their son, Kevin, and his wife, Marina, live in Edam but spend up to 10 days a month helping run the farm. Kevin works in the oil industry while Marina owns a hair salon.

For Kevin, the farm is a pastoral retreat and the place where he and his brother, Randy, grew up.

“Once you get to the farm, there’s no oil around there, it’s very quiet, very peaceful. It’s nice to get away from all the traffic,” he said.

For Marina, who grew up in town, the homestead opens a window to a simpler time.

“For me, it’s fun,” said Marina of the cabin, which only recently got power but remains without plumbing.

“It wasn’t work for me, it was fun.”

Inaccessible roads in winter are among the many challenges that farmers face here.

Glen recalled life as a boy before cellphones and TV, when horses, snowmobiles and tractors were the only way off the farm in winter.

The Foulds make regular treks through the snow to check animals, but a natural spring allows cattle access to water year round, and good fencing, some of it electrified, contain the herd.

The Foulds faced adversity when their family home burned to the ground in 1978, taking with it their cherished mementos but leaving the family unharmed.

“You do what you have to do when you have to do it,” Glen said of the tragedy.

The community stepped in with donations, including a quarter of beef, and the family moved in a cabin from another site.

Glen worked hard over the years to pay the bills by dabbling in ventures from raising sheep to trapping to snowmobile repairs.

He worked as a steam engineer at the Edam hospital while he and Ilene kept a large garden, sold eggs, trucked cream for grocery money and milked cows for the family.

Expansion was not a viable option.

“We had to go big or get out, that’s basically what happened,” said Ilene.

“We tried many things to make a living on the farm. Every time we tried, the government would put a (marketing) board on it or some restriction.”

They keep their workload to a minimum, supervising calving and then hauling cattle to the stockyards when they are market ready.

“We don’t have enough to do independent marketing or satellite selling,” said Kevin.

He said off-farm jobs and the small herd size, which once numbered as many as 80, minimized the damage from the BSE outbreak of 2003 and the resulting low prices.

Glen said the riverbank is best suited for cattle and hay, and the family maintains the grass in its natural state to reap the dividends.

“It never runs out. Tame hay will eventually run itself out, whereas natural grass never will,” he said.

Marina and Glen handle the baling, Kevin cuts the hay and Glen manages the fencing, much of which must be done by hand because of the sloped riverside location.

Now enjoying the slower pace, Ilene and Glen cherish their outdoor life and keep busy with hobbies of painting and restoring Case tractors. They have had opportunities to sell the farm but want to keep it for their children, eight grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

“It’s a place where kids can come and see how life was back then,” said Ilene.