Soil naturally becomes more acidic as it ages, gradually losing the capacity to grow crops as the pH drops. The question is, what can be done about it?

“It’s a natural process,” said Don Flaten, a soil scientist at the University of Manitoba.

“Soils acidify with age as water percolates through them.”

Flaten said old soil is quite acidic, creating a major challenge to food production.

“In most areas of the Canadian Prairies, we’re lucky to have large reserves of the materials that keep the pH high. We have a lot of buffer capacity to stabilize pH with large reserves of calcium and magnesium,” he said.

Read Also

Growing garlic by the thousands in Manitoba

Grower holds a planting party day every fall as a crowd gathers to help put 28,000 plants, and sometimes more, into theground

“But eventually, those reserves will get used up and our soils will gradually become more acidic. Unfortunately, adding lime is very expensive. You’re talking two or three tons per acre of product in some cases.”

A good example of older acidic soil is the Milk River Ridge in Alberta and Cypress Hills in Alberta and Saskatchewan, which were missed by the last glaciers.

As a result, these areas have older soil than the rest of the Prairies, which experienced glacial cultivation.

Western Canada has 6.3 million acres of acidic soil with a pH of six or less, according to Alberta Agriculture. A pH of six is considered to be moderately acidic, while a pH of 5.5 is strongly acidic.

Another 8.5 million acres of soil have a pH of 6.1 to 6.5, which is termed slightly acidic.

“Crop production on these soils will be reduced in the future as soil acidification continues,” retired soil scientist Ross McKenzie said earlier this year.

“In the Peace River region of Alberta and British Columbia, approximately 1.35 million acres of cultivated soils are sufficiently acid to reduce alfalfa growth.”

Moving up the soil ladder, a pH of seven is neutral, 7.5 is slightly alkaline, eight is moderately alkaline and 8.5 and higher is strongly alkaline, high in sodium and classified as saline, sodic or alkaline.

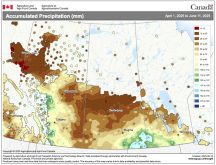

Flaten said pockets of acidic soil exist in southern, central and northern Alberta, west-central Saskatchewan and southeastern and northwestern Manitoba.

“There are different kinds of acidic soils, depending on their background and how they developed,” Flaten said.

The wooded soil band starts in Minnesota and roughly follows the parkland region from southeastern Manitoba, across the northern farming regions of Saskatchewan and into northwestern Alberta.

“These are the gray wooded soils, forested lands that have been cleared for farming. These soils were formed from acidic leaves, needles and rotting wood,” he said.

“In central Alberta, we have the acidic black soils, and we have acidic black soils in Manitoba. Up at Scott, (Sask.), we have the acidic dark brown soils.”

He said farmers are doing more than their share to accelerate soil acidification.

“The nitrogen fertilizers we use are quite acidifying,” he said.

“They are gradually lowering the pH of all our cropland.”

McKenzie agreed: “For the past decade we have noted that the surface pH has been declining slightly in soils across Alberta that are direct seeded. This is primarily the result of acidification caused by nitrogen and sulphur fertilizers over a period of years being added to soil. With conventional tillage, the upper six inches of soil is constantly being disturbed. Therefore, the acidifying effects of N and S have been less noticeable.”

He said a lime application can raise the pH level and rehabilitate acidic soils.

Lime products and formula are available that can be used to raise soil pH, Flaten added.

Retired researcher Stu Brandt from the Scott Research Farm in northwestern Saskatchewan said acidic soil on the Prairies isn’t a new discovery.

He said the station conducted research into liming acidic soil in the 1980s, with plots on the research farm, strips in farmers’ fields and trials at Loon Lake on the northern fringe of farmland.

Brandt said the lime did not show a significant response except in the plots where high rates were applied or when lime was applied to soil with low pH and low phosphorous levels.

“A lot of that lime research was tied to increasing the availability of phosphorus,” Brandt said.

“If availability of P is very low and the soil pH is also very low, there is a high likelihood that you’ll see a good response to lime. We did some liming on the grey-wooded soils up in the Loon Lake area, but the lime didn’t show much response because those soils are relatively high in phosphates.”

He said the Scott research should be factored into any plans to push corn and soybeans further to the northwest on the Prairies.

“Corn, especially, is a very high phosphorus user, so if you put corn and soybeans on land with a low pH, you might find that you need to apply lime.”