Pascal Lamy’s mid-December decision to abort a ministers’ meeting that would have been a last desperate attempt to forge a world trade agreement in 2008 leaves open some fascinating questions for 2009.

Can the World Trade Organization round launched more than seven years ago be resurrected after a hiatus of months if not years?

Are the post-Sept. 11, 2001, goals of defiance and development that helped launch the round in Doha still relevant or even achievable?

The year ends with WTO true believers in a bit of a slump.

Read Also

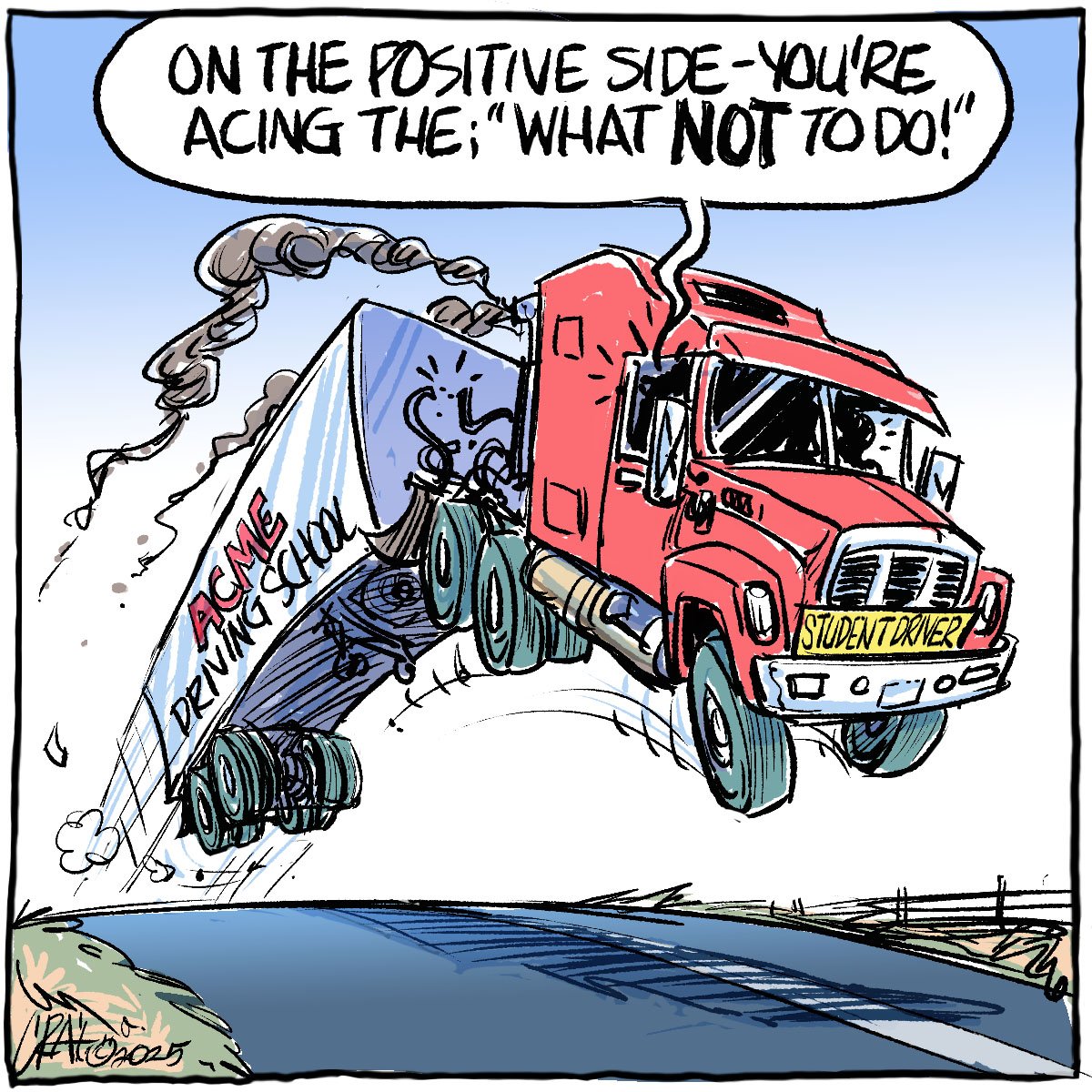

Efforts to improve trucking safety must be applauded

The tragedy of the Humboldt Broncos bus crash prompted calls for renewed efforts to improve safety in the trucking industry, including national mandatory standards.

Despite their optimistic talk of reviving negotiations as early as next summer, surely they can feel the momentum seeping out of the process.

“I suspect this is the practical end of the Doha Round,” says Michael Hart, director of Carleton University’s Centre for Trade Policy and Law in Ottawa.

“Negotiations like this only succeed if enough countries believe they will fix a real problem and I honestly don’t see that now. It is like they are trying to close a deal for the sake of closing a deal. The world has changed and issues have shifted since this round was launched seven years ago.”

It also is far from clear that the new Barack Obama administration, taking over in Washington in late January with a long list of problems and priorities, will see a seven-year-old WTO round as a priority.

Supporters of a deal would argue that trade liberalization at the heart of WTO talks is as relevant in a time of economic crisis as it was in 2001 when launch of the round was seen as a message to terrorists that the world was still functioning.

Protectionism is the timeless problem to be solved, they argue.

But in truth, a deal is not as close as they like to believe.

While a significant package of concessions and potential gains are on the table (an end to export subsidies, real cuts in domestic subsidies and protective tariffs), there remain significant unresolved and difficult issues.

At their core is a fundamental disagreement over how much the proposed new disciplines should apply to developing countries. This question is at the centre of the debate because after all, this is promoted as the “development round.”

There are many other issues as well, including the fact that most of the 153 WTO member countries have yet to weigh in on how a deal would affect them and what sensitive national interests need to be accommodated.

The package now on the table, much touted as the outline of a deal, really is just the handiwork of a handful of major players that Lamy has asked to try to bridge some of the differences.

At some point, each member country will have to decide if what is good for the big guys also works for them. Under WTO rules, each country effectively has a veto if they want to exercise it.

Canada’s rejection of proposals that would undermine supply management protections is just one example of hundreds of sensitive-area objections that probably exist among WTO members who have not yet had their final say.

Hart’s prediction of the end may be too severe but it would be foolish to pin too much hope on the prospect of an early revival and quick resolution.