Traditional deworming practices in horses are under scrutiny because new evidence indicates internal parasites are becoming more resistant to deworming products.

For nearly three decades, traditional programs have advocated deworming at regular intervals. Information about emerging resistance to these products is a good reason to reconsider such practices.

The introduction of ivermectin during the 1980s made deworming products widely available to all horse owners. Previously, veterinary intervention was required to administer the older caustic deworming agents by placing a tube through the horse’s nose down the esophagus and into the stomach chamber.

Read Also

Worrisome drop in grain prices

Prices had been softening for most of the previous month, but heading into the Labour Day long weekend, the price drops were startling.

Initially ivermectin was designed to control and eliminate the immature and adult stages of bloodworms and it did this so effectively that it changed the landscape of the gut, making room for a previously small player in the parasite load of horses: the small strongyles or cyathostomes.

As a result, small strongyles have become a greater health problem in horses that are kept on pasture, in spite of deworming products. These small strongyles have a unique segment in their life cycle that has apparently allowed them to hide from deworming products.

While grazing, horses ingest infective third-stage larvae. The larvae travel in the intestinal system and invade the wall of the large intestine, surrounding themselves in a protective cyst-like structure and setting up housekeeping for an indefinite time.

Poorly understood triggers signal the parasite to continue development, increasing in size and breaking into the lumen of the intestine where they mature to adult form and produce eggs that are released into the environment in a horse’s feces.

Weather conditions permitting, free-living larvae hatch from the eggs and reinfect pastures, perpetuating their life cycle.

With the exception of moxidectin, licensed deworming agents, also known as anthelmintics, do not work at standard doses on the encysted immature stage of the parasite within the wall of the large intestine.

Because of this elusive phase in the small stronglyes’ life cycle and its ability to develop resistance to anthelmintic, careful selection and timing of deworming products is advised.

All drugs licensed in Canada for treatment and prevention of internal parasites in horses belong to three chemical classes, although many products are on the market. The active chemical ingredient is found in the small print on the label.

Because drugs within the same chemical class use the same mechanism of action, parasites that develop resistance to one drug generally develop resistance to all the drugs in that class.

Speculation is that resistance within all three classes will happen eventually.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that resistance is occurring in all classes.

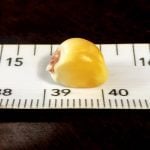

The McMaster Quantitative Fecal Egg Count is a valuable screening tool for gauging the efficiency of a worming product. A predetermined amount of feces from the horse is placed in a solution. A measured amount of solution is then placed in a counting chamber under a microscope, producing a number of parasite eggs per gram of feces.

This test will evaluate the effectiveness of a deworming product when done 10 to 14 days after the product is administered.

This exam provides information about the type, frequency and effectiveness of a treatment.

Opinions differ on contamination thresholds, but the guideline I follow is that 50 to 100 eggs per gram of feces is a low and accepted level of infestation.

We strive for a consistently low level because this seems to provide the horses with a beneficial level of street immunity.

When following a herd of horses, I have found that one or two of them carry the largest worm burden while the remaining horses carry a level of immunity with consistently low egg levels.

Focusing treatment on the horses with high fecal egg counts is economically viable and sustainable.

Keeping fecal egg counts at zero is not necessarily desirable and increases the rate of anthelmintic resistance.

Parasites are opportunists, evolving and developing resistance to deworming agents if that is what is necessary for their survival. Judicious use of these agents allows greater accuracy.

Carol Shwetz is a veterinarian practising in Westlock, Alta.