You can have too much of a good thing. Counter intuitive though it may be, you can even have too much Canadian content in foods labelled as Product of Canada.

As of Jan. 1, 2009, Product of Canada labels could be applied only if at least 98 percent of the product comprised Canadian-produced ingredients. The rule, enacted by the Conservative government, was designed to address complaints about clarity in labelling and inadequacies of previous guidelines.

Before the 98 percent rule came into effect just over one year ago, Product of Canada meant that at least 51 percent of the cost of the product – not necessarily the content – was incurred in Canada.

Read Also

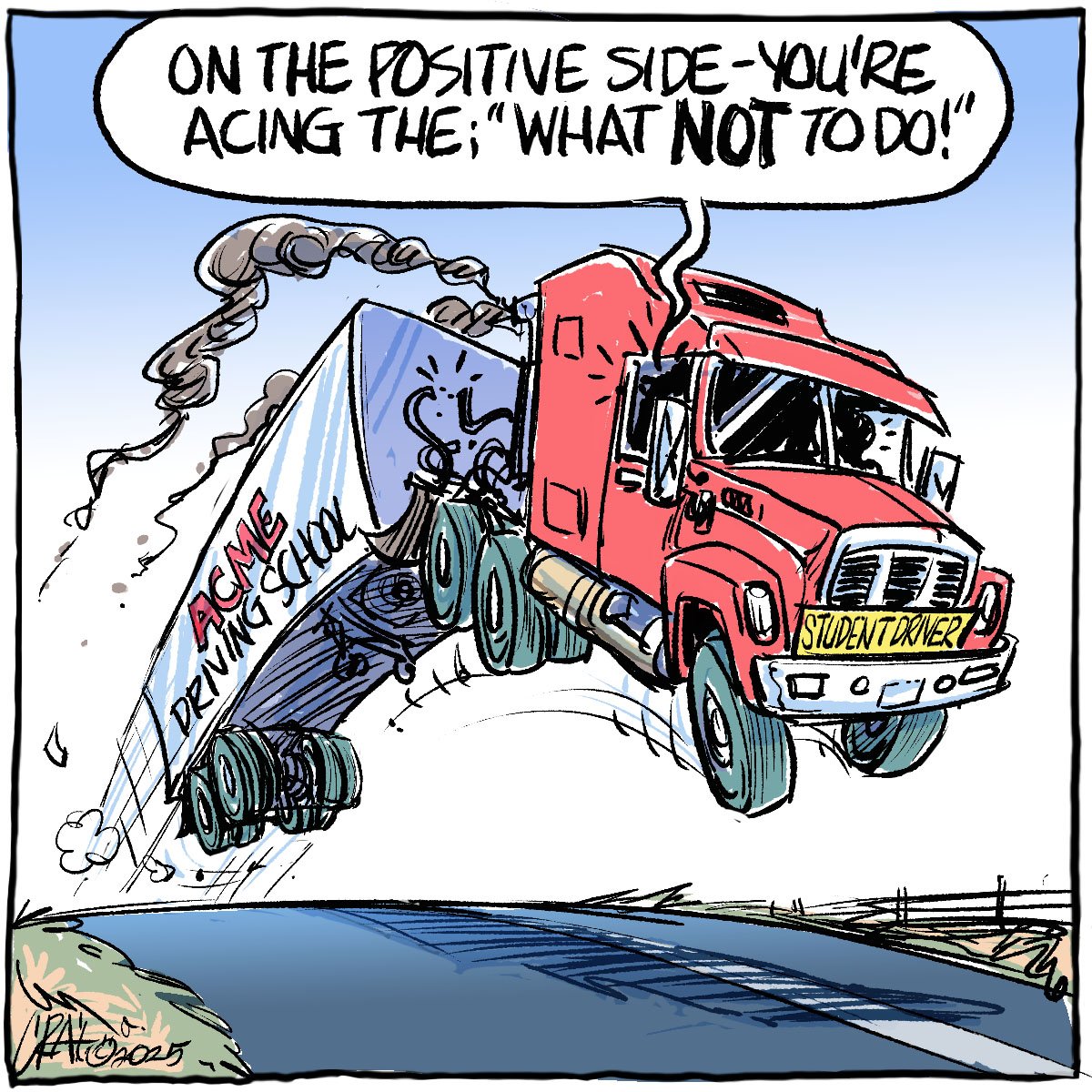

Efforts to improve trucking safety must be applauded

The tragedy of the Humboldt Broncos bus crash prompted calls for renewed efforts to improve safety in the trucking industry, including national mandatory standards.

The result was numerous misleading label scenarios in which grapefruit juice and coffee could be labelled as product of Canada simply because most of the processing and packaging was done here. Chinese honey and many other foreign-originated products could be labelled as Canadian for similar reasons.

Something had to be done, and in May 2008, prime minister Stephen Harper announced the 98 percent rule change so that Product of Canada would signify that products so labelled would contain almost entirely Canadian ingredients.

It was decisive action on the government’s part, in response to a problem that troubled farmers, food processors and consumers.

But none of them asked for such a high threshold. Recommendations arising from 2008 hearings on the matter gave 80 to 85 percent Canadian content as an acceptable level.

Now, one year later, 98 percent Canadian content, with only a few exceptions, has proven almost impossible to achieve in many food products. For example, much of the sugar in processed foods, including ice cream and creamed corn, makes up more that two percent of the total and is purchased outside Canada. That means some Canadian ice creams and corn grown in Canada do not meet the labelling standard.

As well, climate and other circumstances dictate that food processors and manufacturers cannot guarantee a 12 month supply of Canadian ingredients. That means they would have to label their products differently depending on time of year, raising production costs that would likely be passed on to consumers.

Processors have complained that the need for additives in some foods makes the label almost impossible to achieve. Producer groups say the high threshold means they do not have the advantage of a Canadian market that they had expected.

Those expectations are supported through various studies. Loblaws last summer found that 86 percent of respondents agreed that given the option, they would prefer to buy Canadian produce. McDonald’s has made a point of emphasizing its use of Canadian eggs and meat. Consumer groups encourage purchase of local and domestically produced foods.

In late December 2009, federal revenue minister Jean-Pierre Blackburn, who is also minister of state for agriculture, talked about consultations he has undertaken on the matter.

He hinted at changes.

A recent Canadian Federation of Agriculture news release told of its desire to see “the limit of eligible foreign content increased from two percent of total ingredients to 15 percent if the principal food that is labelled is made of 100 percent Canadian ingredients.”

In view of problems encountered with the 98 percent rule, 85 percent seems a reasonable compromise, particularly if such a change is accompanied by a good communications program that informs Canadian consumers about what the Product of Canada label means.

Somewhere there is comfortable ground between the extremes of 51 percent of cost and 98 percent of ingredients. In the coming year, the government should take specific steps to find it.

Bruce Dyck, Terry Fries, Barb Glen, D’Arce McMillan and Ken Zacharias collaborate in the writing of Western Producer editorials.