Bigger farms, fewer farmers — those results from the 2011 Census of Agriculture are hardly surprising. It’s the well-established, long-term trend.

However, there’s more to the numbers than meets the eye.

According to the census statistics, the average farm size in Saskatchewan has increased to 1,668 acres while Alberta is 1,168 and Manitoba is 1,135.

The census has the trend right, but the numbers don’t make sense. Farms of that size are now considered small, not average. The numbers are likely being skewed by people who retain small holdings and like to have the perks and status of calling themselves farmers.

Read Also

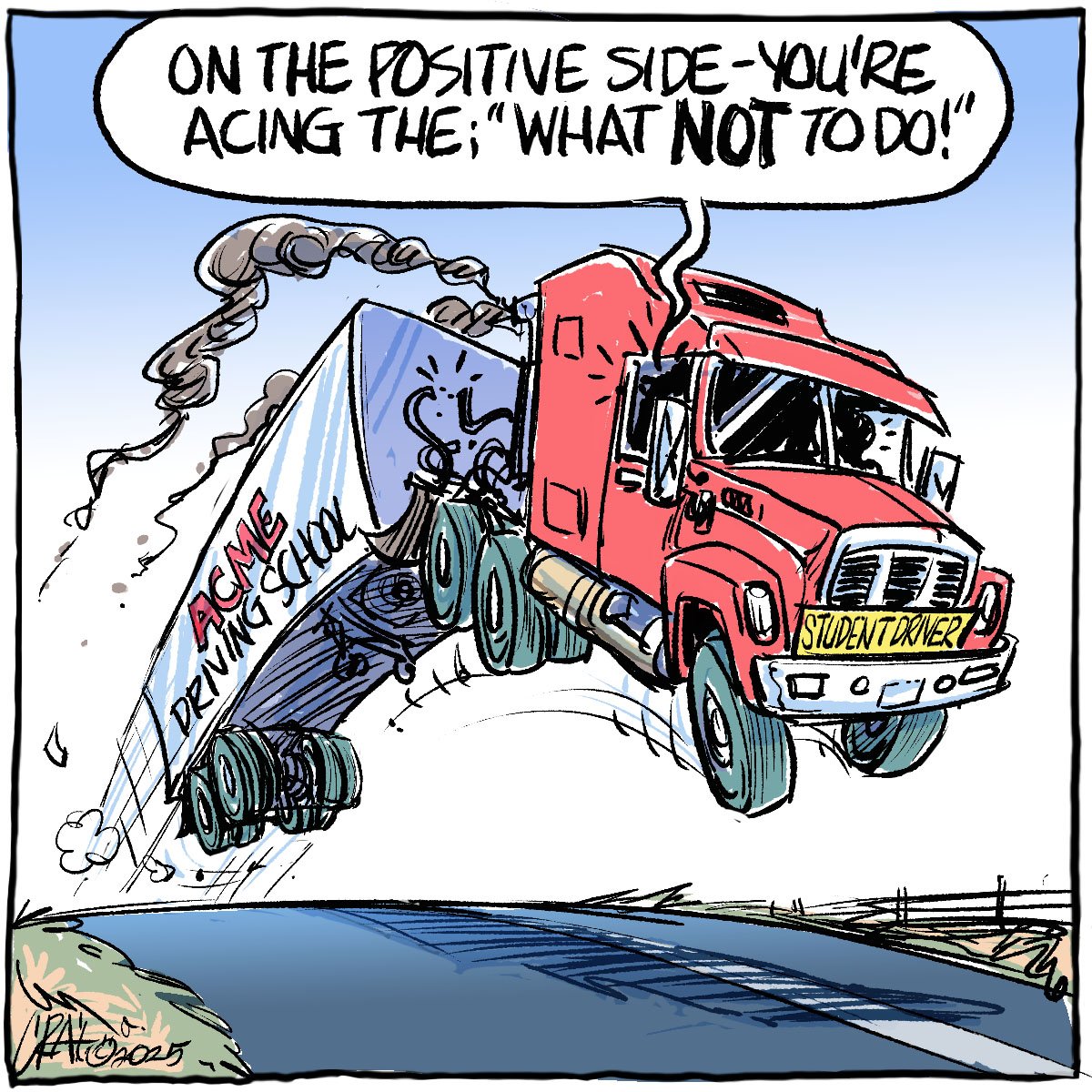

Efforts to improve trucking safety must be applauded

The tragedy of the Humboldt Broncos bus crash prompted calls for renewed efforts to improve safety in the trucking industry, including national mandatory standards.

Gross farm receipts show the same thing. There continue to be a lot of small farms.

Twenty percent of Canadian farms have gross receipts of less than $10,000. Whether it’s a semi-retired farmer on the Prairies taking a crop share on a quarter or two of land or a young person in Ontario selling a small quantity of vegetables at a farmers’ market, these are not typical of commercial operations.

More than 60 percent of census farms have less than $100,000 in gross receipts. This perpetuates the myth of quaint little farms, but it’s just not the reality. At current grain prices, a farm can gross $100,000 with just 250 acres of canola or 500 acres of wheat at average yields.

Those farms with gross revenue of less than $100,000 accounted for less than 10 percent of total farm receipts.

Large farms grossing more than $1 million a year are relatively few in number, but that’s where most of the country’s production is coming from. The census shows 9,602 farms grossing $1 million or more. That’s only 4.7 percent of all farms, but they accounted for 49.1 percent of total gross receipts.

A lot is being made of the aging of the farm population, with the 2011 Census of Agriculture marking the first time that the largest age category is producers older than 55 — an amazing 48.3 percent of farm operators. Meanwhile, farm operators younger than 35 accounted for just 8.2 percent of the total.

What’s missing from those statistics and what may come out with more analysis is the gross revenue to age correlation. The oldest category of farm operators probably includes a lot of the big, well-established farms as well as semi-retired producers who have relatively small holdings.

Not surprisingly, land rental is gradually but steadily becoming more common.

Less than 60 percent of farmland is owned by the operator. Back in 1976, it was 70 percent. Statistics Canada makes the point that land rental is a less capital-intensive means of expanding. As well, investors are buying farmland.

Only 19 percent of farms are incorporated, but this is another stat skewed by the large number of relatively small operations.

Most farms grossing more than $500,000 a year are incorporated. Even in the $250,000 to $499,999 category, nearly 37 percent of the operations are incorporated.

So, where should farm policy be directed? Should farm programs and policies be aimed at the majority of producers grossing less than $100,000 in an attempt to make them more viable?

Or should governments look to support the $1 million farms that while relatively few in number are accounting for nearly half of total receipts?

And what does the future hold for those of us who fall somewhere between big and small?