“To be absolutely certain about something, one must know everything or nothing about it.” — Olin Miller

In the last 20 years working as a journalist, I’ve learned a few mistakes to avoid.

Such as: don’t misspell the name of a small town. People in that town will notice.

Sorry, again, Aylsham, Sask.

Also, I’ve learned that certainty is something all reporters should avoid. It’s high up on the avoid list, along with stories that criticize firefighters and nurses.

Read Also

Phosphate prices to remain high

Phosphate prices are expected to remain elevated, according to Mosaic’s president.

Once you are certain about a particular topic or issue, that means you stop asking questions, or only ask questions of people who agree with you.

Which isn’t a great idea, seeing how journalists should be curious and should always seek out more perspectives.

The same is true for scientists.

If a university scientist or government academic is certain that their research findings and recommendations are the unquestionable truth, they have probably lost their way.

They likely spend most of their time lecturing, hectoring and arguing with those who disagree with their version of the truth.

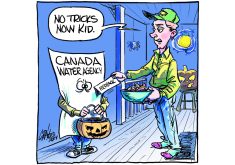

A good example of the danger of certainty is the ongoing issue of nitrous oxide emissions from nitrogen fertilizer. The federal government wants Canadian farmers to reduce emissions by 30 percent from 2020 levels by 2030. The plan is voluntary and grain growers are not required to change their fertilizer practices, but the government target has become a wedge issue in Canadian farm politics.

On one side of the wedge are a group of scientists, self-righteous journalists, government policy makers, environmental activists and others who are certain that modern agriculture is not sustainable and Canadian farmers must change their wicked ways.

If producers would only listen to their wisdom, what a wonderful world it would be.

On the other side of the wedge are some farmers and ag industry leaders who are convinced that modern agriculture is already sustainable. By adopting reduced tillage, eliminating summerfallow and by increasing production per acre, Canadian farmers have taken action to cut greenhouse gas emissions and store more carbon in the soil. Nothing to see here. Everything is great.

Between those two extremes is the largest group.

There are thousands of farmers, agronomists and others employed in the ag sector who are proud of the progress than Canadian agriculture has made over the last 35 years. Many have changed their practices to conserve the soil, some have preserved wetlands and maintained habitat for wildlife and overall, farmers have dramatically increased the average yield per acre.

But the thousands in the middle don’t believe things are perfect. Much more progress can be made on sustainability.

Maybe they could add a legume to the crop rotation to diversify their risk and cut their nitrogen use.

Or maybe they could try winter wheat, so ducks have a nesting habitat in the spring. And maybe they could take a longer look at the 4R approach to manage fertilizer (right rate, right time, right place, right source), which might improve their fertilizer efficiency.

Unfortunately, the federal government plan to cut fertilizer emissions by 30 percent has put those reasonable folks in an awkward position.

When a wedge issue is created, people must choose one side of the wedge or the other.

Are farmers going to take the side of a group of scientists, journalists, environmental activists and government policy makers, who are certain that crop production is not sustainable, who believe that modern farming is destroying the planet?

That seems unlikely.

Which means that thousands of producers, who might be willing to alter their practices and become more sustainable, are now siding with a smaller group who are certain that agriculture is innocent of all environmental sins.

To make actual progress on sustainability and get more farmers on board, it might be necessary to remove the wedge. Maybe the government target of cutting emissions by 30 percent can quietly disappear.

That would be nice. And it might reduce some of the “us” versus “them” language that plagues the ag industry.

If the federal government got rid of the 30 percent target, it would probably be helpful.

But I’m certain it won’t happen.