REGINA – Two weeks ago, the most important people from the oil and gas industry gathered in Calgary for the annual World Petroleum Congress.

One of the issues on their agenda was how high the industry’s cartel of exporting countries should set the price of oil.

Last week, it was the grain industry’s turn, as hundreds of delegates from around the world gathered in Regina for the International Grains Council’s annual conference.

But unfortunately for wheat growers, there is no export cartel that can decide how high to set the price of wheat.

Read Also

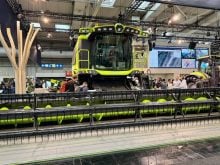

Agritechnica Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year

Agritechnica 2025 Day 3: Hybrid drive for a combine, data standards keep up to tech change and tractors of the year.

All that the assembled industry leaders could offer farmers suffering from low prices were reassuring words and vague projections.

“There is some hope and confidence the market will improve, but how far and how fast remains to be seen,” IGC executive director Germain Denis said as the two-day meeting came to a close.

Gus Schumacher, in charge of the United States Department of Agriculture’s foreign agriculture service, said all the fundamentals point to a positive market outlook.

For the third consecutive year world wheat consumption will exceed production, global stocks will be even lower than in 1995-96 when prices soared to record levels, and trade is expected to be at its highest level in a decade.

Yet despite those bullish signs, the USDA is forecasting only a modest increase in prices.

“Frankly, we are looking at another buyer’s market in the year ahead, unless production falls significantly short of current projections.”

The problem is that while global stocks are a relatively low 106 million tonnes, the stocks held by the major exporters total 50 million tonnes, nearly double their level five years ago.

The IGC’s monthly market report has slightly different numbers than the USDA. The council is projecting 2000-01 ending stocks of 105 million tonnes, down from 119 million a year ago, and says the five major exporters will hold stocks totalling 49 million tonnes.

In the early 1980s, farm organizations and politicians from the major exporting nations often talked about the possibility of setting up a grain or wheat export cartel to control supplies and prices. But that idea is no longer on the table when the world’s grain industry gets together.

“There is no disposition internationally to go that route,” said Denis.

Such a major regulatory intervention in the market would go against the basic thrust of the last 20 years of making the world grain market more open and less subject to government intervention.

“A cartel is simply not the way to have a sound market-based grain economy.”

But beyond that, the world would never accept the idea of the price and supply of a basic food like wheat being controlled by four or five governments.

He added that other countries would respond by increasing their own production and the power of the cartel wouldn’t last.

The best course for exporters is to have a wide open, fully functioning commercial market, in which importers know they can rely on exporters for consistent supplies of good quality product at a reasonable price.

Brian White, vice-president of market analysis for the Canadian Wheat Board, said “the largest exporter of wheat and coarse grains in the world is the U.S. and as a matter of principle, they’re not interested in any kind of arrangement.”

For more stories on the IGC meetings, see pages 13 & 21.